This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in

Captive Canada:

Renditions of the Peaceable Kingdom at War,

from Narratives of WWI and the Red Scare to the Mass Internment of Civilians

Issue #68 of

Press for Conversion (Spring 2016),

pp.15-21.

Press for Conversion! is the magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).

Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this

coupon,

or use the paypal link on our webpage.

If you quote from or

use this article, please cite the source above and encourage people to

subscribe. Thanks.

Here is the pdf version of this

article as it appears in Press for Conversion!

First Nations, First Captives:

Genocidal Precedents for Canadian Concentration Camps

By Richard Sanders, Coordinator, Coalition to

Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT)

WWI

was not the first time that thousands of people had been forced into captivity

for threatening the “peace, order and good government of Canada.”1 In fact,

Conservative and Liberal governments alike already had a well-established

modus operandi that used mass captivity to subjugate so-called “foreign”

enemies on the homefront.

WWI

was not the first time that thousands of people had been forced into captivity

for threatening the “peace, order and good government of Canada.”1 In fact,

Conservative and Liberal governments alike already had a well-established

modus operandi that used mass captivity to subjugate so-called “foreign”

enemies on the homefront.

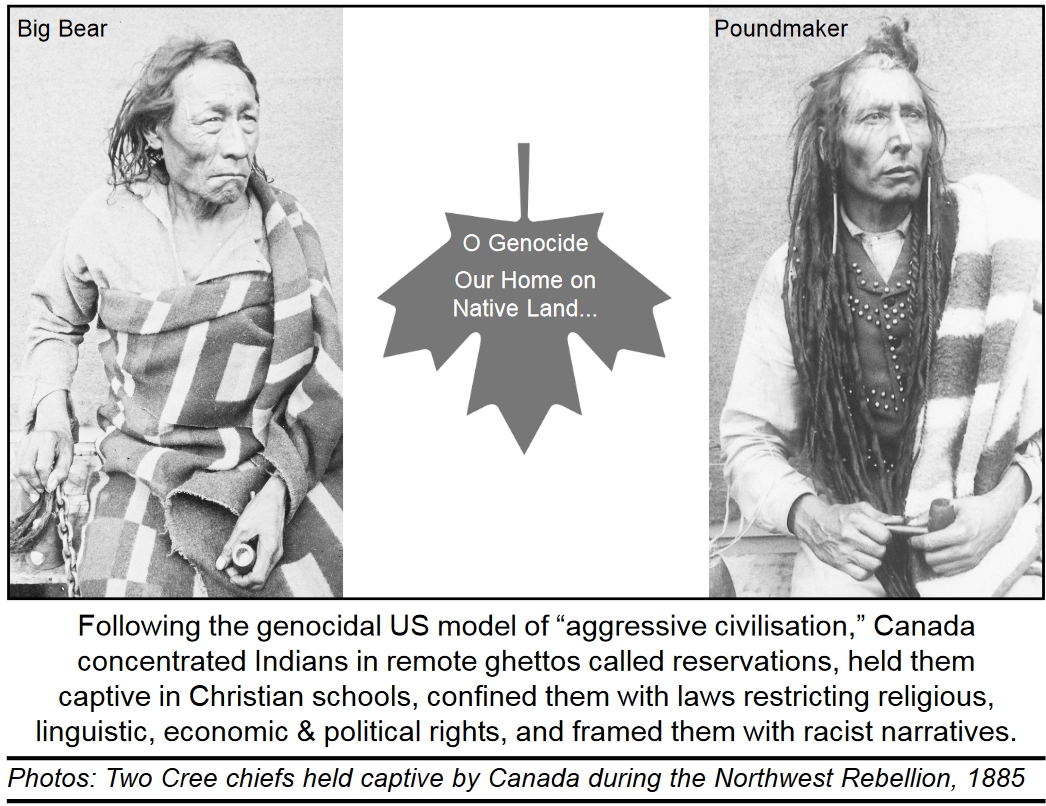

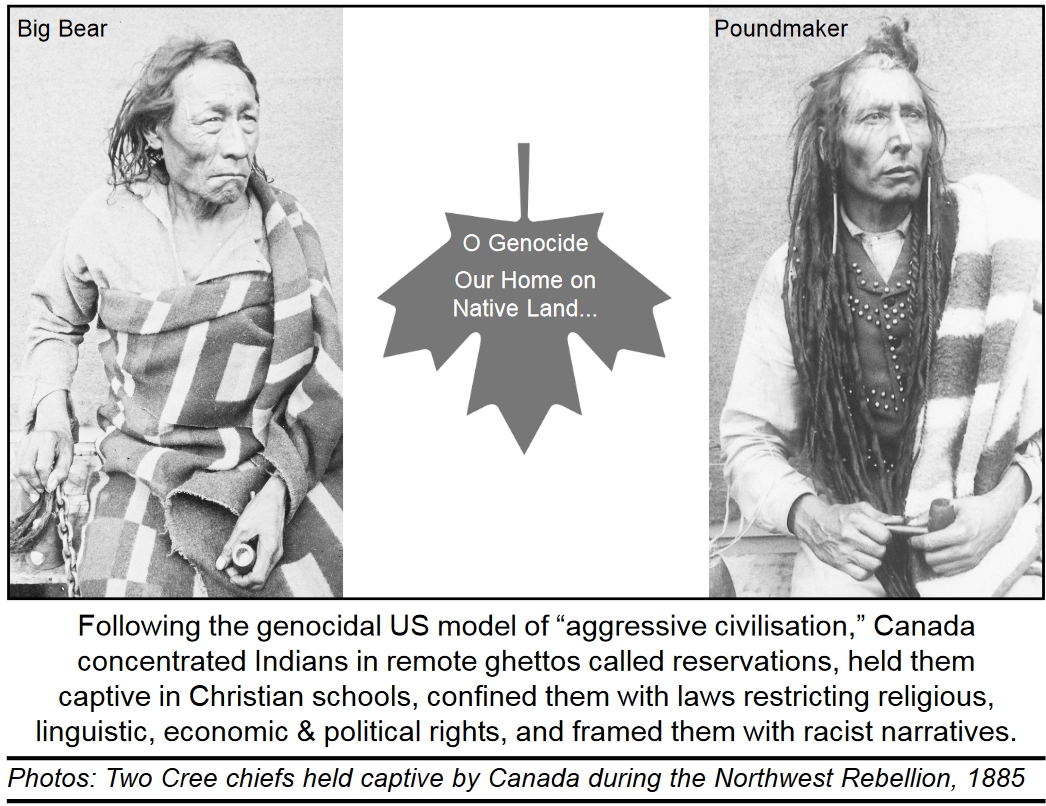

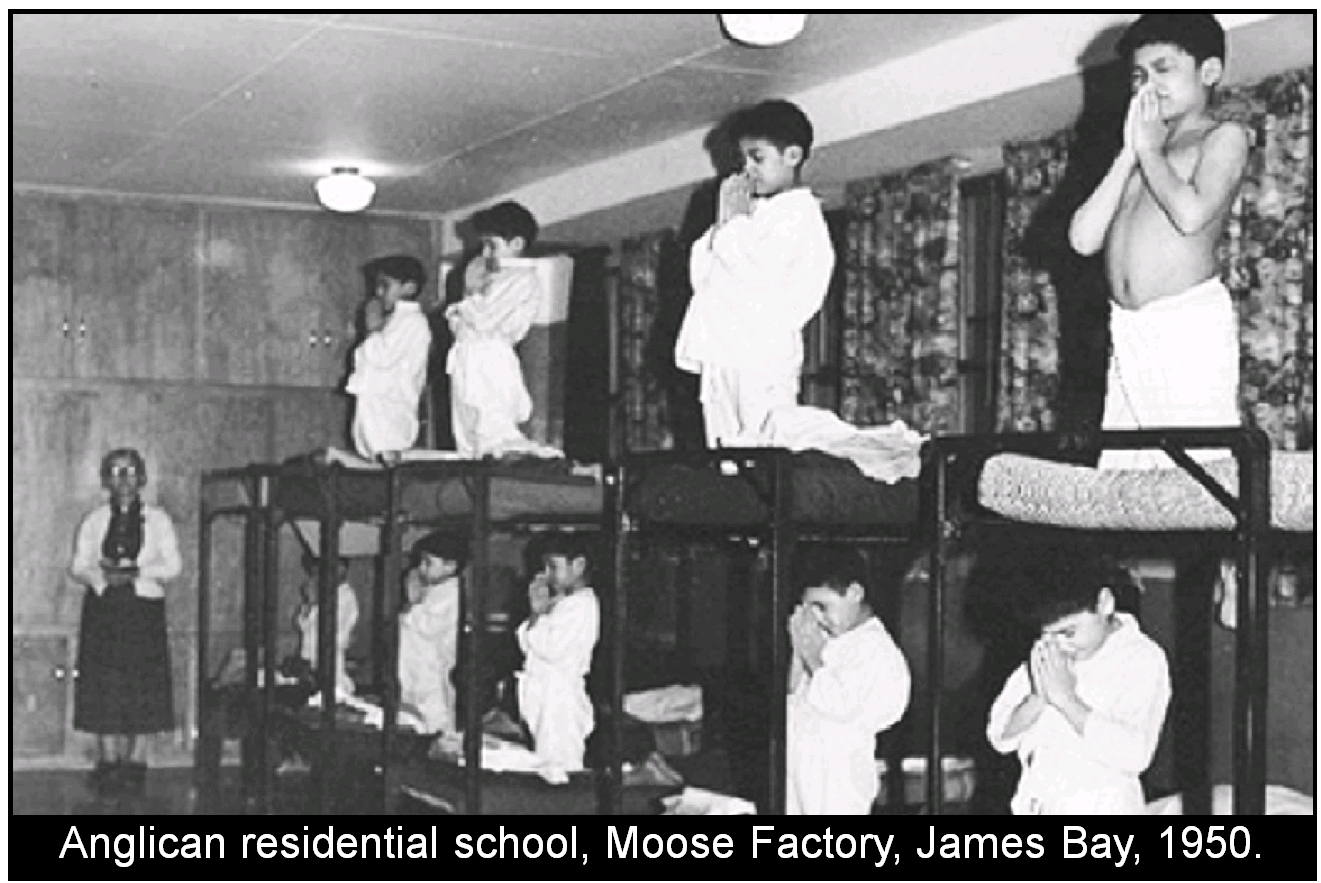

Canada’s

20th-century internment camps did not arise in a vacuum. They continued a

long-standing tradition of forcing targeted populations into isolated rural

locations across the country. Canada’s system of mass confinement followed the

US

model for segregating Aboriginals into remote ghettos, called reserves. But this

was only one weapon in a multidimensional war to destroy First Nations. Besides

restricting physical movements, elites used a diversity of tactics, including

residential schools, to hold Indigenous people in place. They were also confined

within the bounds of a genocidal legal framework that restrained religious,

linguistic, social, economic and political freedoms.

Such

multidisciplinary genocide cannot be committed by a few sociopaths. Large scale

atrocities can only be achieved by an institutionalised sociopathy. Those

with “Antisocial Personality Disorder” are defined by the US Department of

Health as individuals with “a long-term pattern of manipulating, exploiting or

violating the rights of others. This behavior is often criminal.”2 When state

agencies, NGOs or corporations run programs or businesses that inflict these

same abuses —albeit on a vastly more devastating scale—they go

undiagnosed, at least by those rendered prisoner by the reassuring narratives of

captive institutions.

Those

who are able to free themselves from the confining frames of thought and

language imposed by sociopathic institutions, sometimes dare to speak out

against the normalisation of antisocial policies. By trying to liberate those

who remain enslaved within the narrative webs spun by abusive institutions,

activists may be diagnosed as rebels, radicals, conspiracy theorists or,

ironically, as psychopaths with “Antisocial Personality Disorder.”

A

century ago, racist and xenophobic views were the norm in Canada. Widespread

antisocial pathology was pandemic throughout the country. The largest and most

highly-respected religious bodies were captivated by this social illness. This

is well illustrated by the Churches’ enthusiastic collaboration with government

agencies to plan, conduct, justify and cover-up the genocidal programs of mass

captivity inflicted on Indigenous peoples.

But

long before Aboriginals were forced into the confinement of reserves and

residential schools in the 1880s, Canadians happily profited from the

institution of chattel slavery. For two centuries, Blacks and Indians were

subjected to the “legalized” captivity and forced labour practised by British

and French colonialists. While prominent members of Canada’s Catholic and

AngloProtestant churches owned slaves, these institutions also helped perpetuate

slavery with Biblical narratives to rationalise their antisocial pathology.

These

long-standing patterns of racist, institutionalised abuse and exploitation are

the sociopathic precedents for Canada’s widely-supported, mass internment of

foreigners and political radicals that began with the pretext of WWI.

Perhaps the most alarming aspect in this history of sociopathy is that

progressive, reform-minded Christians—both Protestant and Catholic—were

entrapped by Canada’s mass psychosis. Although genuinely sincere in their work,

missionaries were restrained by the straightjacket of a widespread, cultural

pathology.

Those

captured heart and mind by predatory institutions, and working within the strict

confines of their myths and narratives, felt compelled to “uplift” peoples who

they saw as inferiour, uncivilised, unChristian and unCanadian. Unable to

perceive social reality, and blind to the horrors that their actions were having

on others, well-meaning Christians were spellbound by the sociopathy of Canada’s

domineering Eurocentric delusions of grandeur.

This

social illness went far beyond mere racism and ethnocentrism to become an

enslaving cultural narcissism. Those enthralled by the anti-social narratives of

Canada’s

dominant religious and political institutions were confined by arrogant hubris,

an entitled sense of superiourity, and a fearmongering paranoia that “strangers”

are inherently inferior, dangerous and evil.

Hamstrung by myths of national exceptionalism, many Canadians took up the

imperialist call of the “white man’s burden...to serve your captives’ need,”

those “new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child.”3 Good Christians

justified their genocidal efforts to rend other cultures asunder, with such

altruistic goals as civilisation, education and morality. Immured by grand

imperial delusions, Canadian nationalists believed that they were building a

model country that was bound by destiny to lead the world. As Prime Minister

Sir Wilfrid Laurier proclaimed in 1904, to cheers from Liberals and

Conservatives alike, “the Twentieth Century belongs to Canada.”4 This

nonpartisan fantasy of national superiourity was ingrained, not only in the

patrician psyche, but in the mindset of mainstream citizens. The country was

gripped by a widespread social malady that can aptly be called the Canada

Syndrome. (See pp.2-4.)

The

delusion that as a superior nation we should sow our “Canadian values” abroad,

grew from an earlier narrative meme of so-called “Christian values.” George

Emery, in his pioneering history of prairie Methodism, described the prevailing

AngloProtestant hegemony saying Canadians believed “Christian values would be

menaced throughout the dominion if the west, with its enormous material

potential, were not won for Christ.”5 (See “Occupation(al) Psychosis...,” p.18.)

Social Gospel and Social Progress

Some of the loudest voices

of Canadian nativism were leaders of the Social Gospel, a progressive strain of

Christianity that prospered from the 1880s until the early 1920s. Historian

Richard Allen defined this reform movement, by saying the

“social

gospel rested on the premise that Christianity was a social religion, concerned

...with the quality of human relations on this earth.... [I]t was a call for men

to find the meaning of their lives in seeking...the Kingdom of God in the very

fabric of society.”6

The Social Gospel included

“advocates of direct social assistance; social purists; those who advocated a

change of attitude as the means to social change; state interventionists; and

socialists.”7

Leaders of the Social

Gospel were usually white, middle-class, AngloProtestant missionaries or

clergymen. Driven to “uplift” the less fortunate, these reformers wanted to help

inferiour classes and races to deal with growing social, moral and economic

problems of industrialisation.

The Social Gospel, said

Mariana Valverde, was an effort to “humanize and/or Christianize the political

economy of urban-industrial capitalism.” Valverde is a University of

Toronto criminology professor who authored a classic text on

Canada’s social purity movement. “Prophets” of

the Social Gospel, she has said

“were

generally moderately left of centre, but included such mainstream figures as

W.L.Mackenzie King, who ... was influenced by social gospel ideas in his popular

1919 book, Industry and Humanity.”8

Before

becoming Canada’s

longest-serving Prime Minister, King was “an ardent social gospeller,” said

historians Douglas Francis and Chris Kitzan. King believed that his political

mission on earth was divinely inspired. Calling himself “a true servant of God

helping to make the Kingdom of Heaven prevail on Earth,” King explained: “This

is what I love politics for.”9

Methodism Led the Way

Most Social Gospel leaders

belonged to the Methodist Church, which adopted its “Social Creed” in 1908. Capturing the reformist

spirit of the Social Gospel, it was a rallying cry for the whole progressive

movement. The Creed declared it “the duty of all Christian people to concern

themselves directly with certain practical industrial problems.” Among these

were achieving “the right of workers to some protection against the hardships

often resulting from the swift crises of industrial change,” “the abolition of

child labor,” and “the abatement of poverty.” Methodists also offered a “pledge

of sympathy and of help” to those “seeking to lift the crushing burdens of the

poor, and to reduce the hardships and uphold the dignity of labor.”10

Canada’s Methodist

Church was a powerful force in Anglocentric settler culture. Like an invasive

non-native species, it spread quickly across western

Canada, and had a devastating impact on

Indigenous peoples. Between 1891 and 1911, Canada’s prairie population rose

almost fivefold, from 220,000 to 1.32 million.11 Between 1896 and 1914, during

the Social-Gospel heyday, there was a tripling in the prairie Methodist fold,

and its churches grew in number from 180 to 562.12

Emery described prairie

Methodists as “part of the predatory white settler population”13 that did not

lament the devastation of the Aboriginal population. In fact, he points out

that:

“During the 1870s and 1880s

Methodist missionaries acted as advance agents for the white settler society.

They favoured the slaughter of the buffalo herds, the government’s native

treaties and...the reserve system.”14

To aid

in this genocide, the church was happy to cozy up to Canada’s economic elites.

As political scientist Kenneth McNaught said, “the Methodist church in the

1880’s and 1890’s was consolidating itself as a church of the

well-to-do.”15 Methodists were later central in forming the United Church of

Canada (UCC). In 1925, when Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregational churches

merged, the UCC took over the fifteen Methodist and nine Presbyterian

residential schools.16

Teaching

“The Three Cs”

Teaching

“The Three Cs”

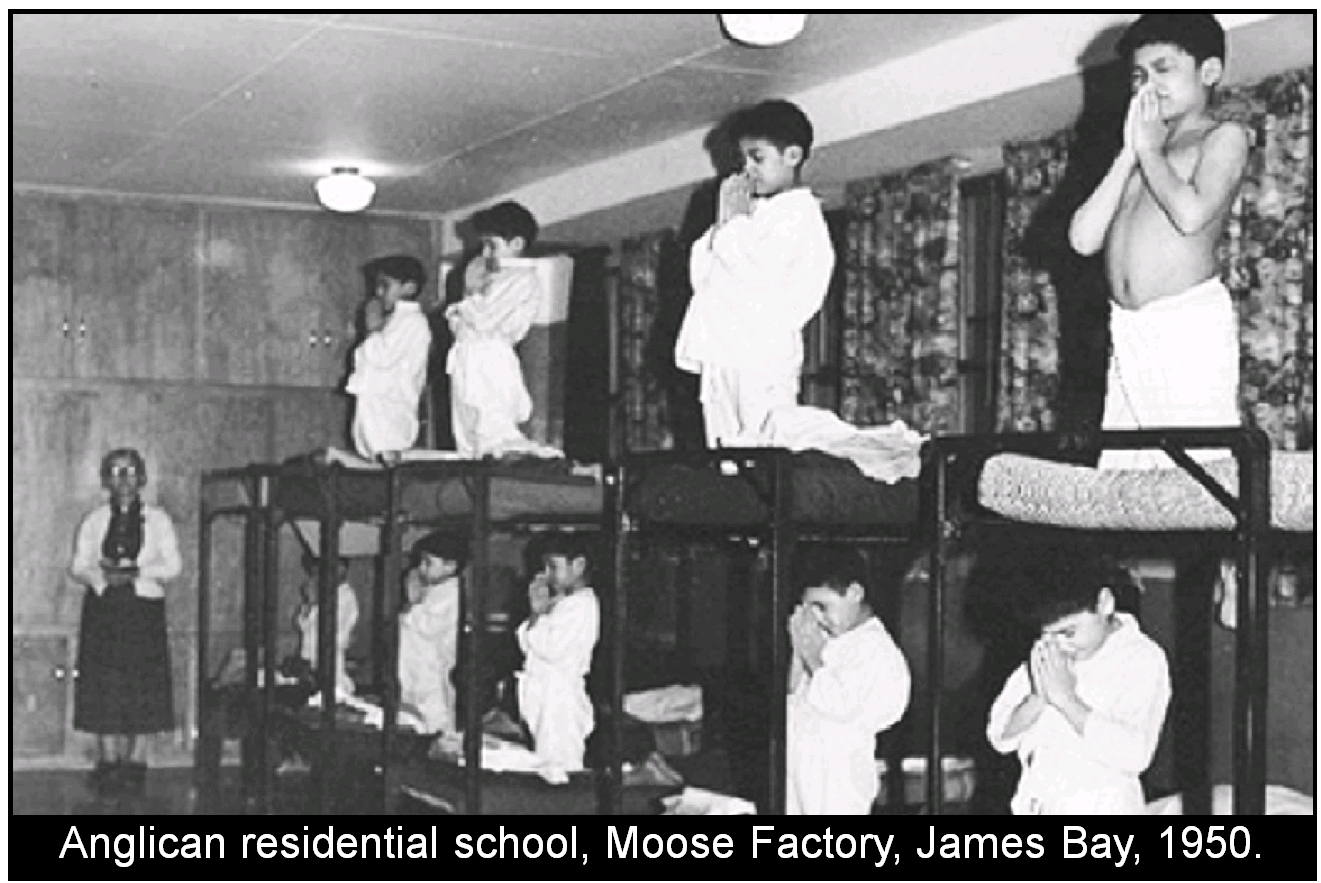

As Methodists and other

Christians spread across the Canadian prairies in the 1880s, they brought a

growth in residential schools. Rather than imparting the traditional “Three Rs,”

church schools targeted Aboriginal children with “The Three Cs,” Civilise,

Christianise and Canadianise.

Of the sixteen Methodist

residential schools built between 1838 and 1975, all but two were in the West.

Their earliest efforts to “uplift” Indian children began with two Ontario

schools in 1838 and 1848. Its first three residential schools in western Canada

began in the late 1870s. Six more were founded there in the 1880s, two in the

1890s, another two in 1900, and their last one opened in 1919.17 Using opening

and closing dates of these well-meaning, but genocidal, Methodist schools, we

can calculate that each school operated for an average of 66 years. Cumulatively

then, the 14 Methodist residential schools in western Canada inflicted the

“Three Cs” for a total of 925 years. The toll on Indian lives is still being

felt.

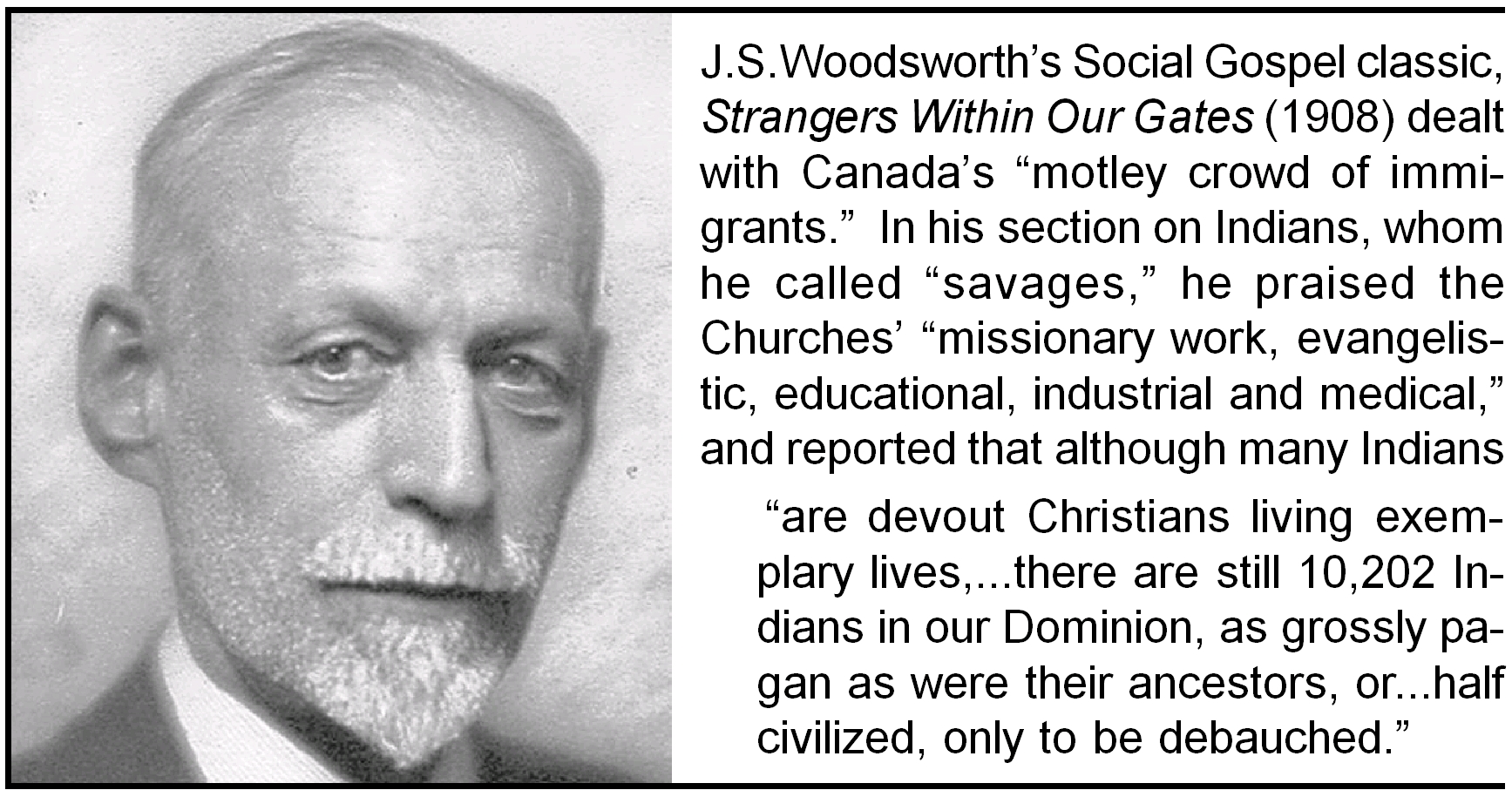

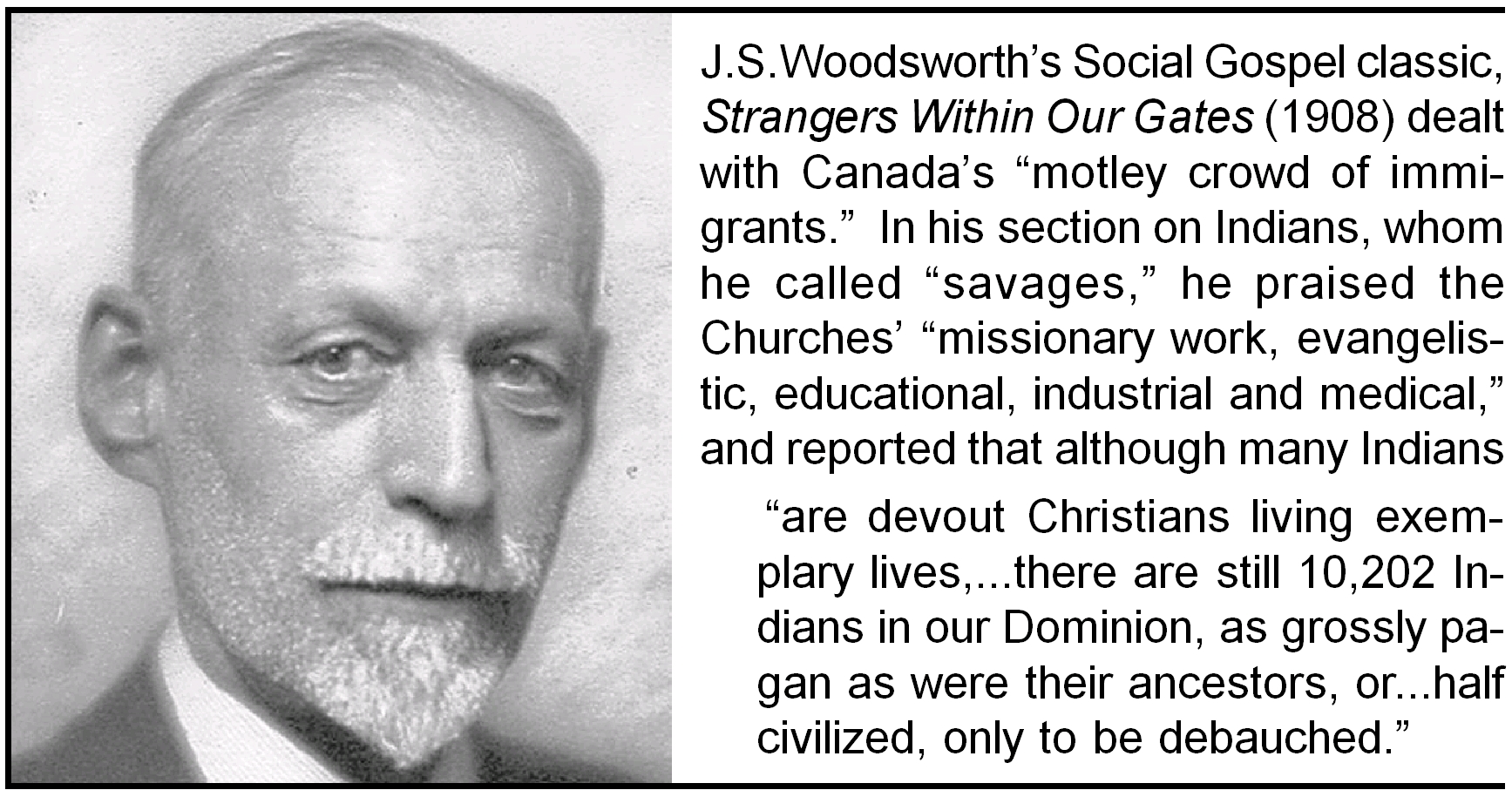

Among the Methodists who

lavished praise upon missionaries for their fine efforts to Canadianise,

civilise and Christianise the Indians under their control, was

Rev.J.S.Woodsworth. In his Social-Gospel classic Strangers Within Our Gates

(1908), Woodsworth noted that:

“

"Much missionary work, evangelistic, educational, industrial and medical, has

been done among the Indians. Many are devout Christians living exemplary lives,

but there are still 10,202 Indians in our Dominion, as grossly pagan as were

their ancestors, or...half civilized, only to be debauched.”18

Strangely enough,

Woodsworth’s book on “strangers” and “newcomers” to Canada included a section on

Indians. It relies heavily on two tracts from the Methodist Department of

Missionary Literature: Indian Education in the North West, by

Rev.Thompson Ferrier, and The British Columbia Indian and his Future, by

Rev.R. Whittington. Ferrier’s work concluded:

“

"The Indian problem is not solved, but it must not be given up, and it

need not be deserted in despair until there is a proper and final solution.

I believe it possible to civilize, educate and Christianize the Indian.”19

(Emphasis added.)

Rev. Whittington, who led

the Methodist Indian Missions in BC, also praised his Church’s residential

schools by speaking of “the noble band of teachers, who daily and quietly are

really laying the foundations of the future in the souls as well as the minds of

our Indian children.”20

The

rapid population growth of prairie settlers and the boom in churches and

residential schools, benefitted the imperial project known as Canada. Westward

expansion of Canadian “civilisation” was a national crusade of Biblical

proportions. Methodists, like Woodsworth, with their blessed rage for Social

Gospel progress, took themselves and their godly mission far too seriously.

“[I]n concert with other Protestants, Methodists were the self-appointed

guardians of Protestant Christian values in society,” said Emery. “[T]hey

assumed that the perpetuation of Protestantism was vital to the nation-building

process.”21 As prominent Presbyterian Social Gospeller Rev.Charles Gordon

proclaimed in 1909, “it is the Christian Church ...more than all other forces

put together, that has to do with the making of a nation.”22

The

Methodist Church, Emery wrote, also exhibited “an aggressive nationalism” that

“opposed the penetration of the west by rival cultures from French Canada and

Europe.” The church fought hard for English-language public

schools because it was preoccupied with assimilating Francophones and other

nonAnglo aliens. Methodists also created missions to “Protestantize the

Europeans.”23 These were tasked with assimilating east Europeans, mostly

Ukrainians, in the so-called “Austrian Missions” of northern Alberta, and

Winnipeg’s All People’s Mission24 where Woodsworth worked (1908-1913).

Nation-Building Myths

The

role of religious narratives in Canada’s nation-building experiment is explored

by Douglas Francis and Chris Kitzan. In The Prairie West as Promised Land,

they show how Biblical illusions were used to express and structure the

narrative myths of Anglo settlers. The “Promised-Land” image that they

fabricated “became the dominant perception of the region during the

formative years,” from 1850 to WWI.25

Francis and Kitzen see

three main versions of the Christian mythology that captured Canadian settlers’

imagination:

(1) The

“myth pictured the Prairie West as an Edenic paradise” that was “flowing with

milk and honey,”

(2)

“Social gospellers believed that the Prairie West was destined to be a New

Jerusalem,” where “virtuous and morally upright” settlers could establish their

“Kingdom of God on Earth,” and

(3) The

prairies were a “land of opportunity” “free of the limitations of privilege and

traditions that hampered advancement.” They saw it “as a tabula rasa—a

blank sheet—upon which each individual could write his or her own destiny of

success, wealth and happiness.”26

Trapping Natives & Nativists

But all was not perfect in

the Social Gospel paradise, especially for Aboriginals. While building a “New

Jerusalem” paved the way for Christianity to be writ large across the “empty”

prairies, it was a death knell for First Nations. Long before AngloProtestants

turned their bigotry against east Europeans in WWI, they had pegged Indians as

the needy targets of uplift. Penned as a primitive savages and heathens,

Aboriginals were the first nations to be forced into mass captivity by Canadian

settlers.

From the first visits of

Europeans to what they came to call Canada, Indigenous people had been

kidnapped, enslaved and converted. European monarchs and their churches

authorised imperial agents to conquer and control the human and natural

resources of the new-found lands. Forced to relocate their communities,

confined to reservations, coerced into residential schools and bound by the

Indian Act, Aboriginal people have been held physically, socially and legally

captive throughout Canadian history.

But

members of Canada’s

captor society were also held hostage. Trapped within the narrow-minded confines

of a racist worldview, many settlers were bound by the nativism that riddled

Canada’s largest religious, economic and political bodies. Among the leading

advocates of this xenophobia were the Social Gospel’s top, influence pedlars.

Their bigotry against Indians was as boundless as the prairie sky. Thus

shackled, Social Gospellers mounted no resistance to

Canada’s

genocide of Aboriginals. They saw no need.

In

fact, these progressives were bound and determined to administer the very

injustices that they should have been protesting. Brimming with good

intentions, many well-meaning souls stepped forward to clear the path toward

what they saw as heaven on earth. But instead, they forged a genocidal road to

hell for all Indigenous peoples standing in their way.

By the

late 1800s, Canada’s

crusade to expand Britain’s imperial vision across the prairies, was in full

swing. To implement this plunderous policy, which dispossessed Indians of their

land, Canadian authorities imposed severe restrictions on Aboriginal mobility

and culture. Churches and state institutions united to impose genocidal programs

of physical captivity and cultural assimilation that could only succeed with the

willing participation of many, well-intentioned Canadians.

Bound by Legal Fictions

The

ludicrous idea that western Canada was an empty slate, devoid of humanity, was a

restatement of the ancient “Discovery Doctrine.” For 400 years, this legal

fiction justified the genocidal conquest of the Americas for the profit of

European monarchs and Church authorities.

The

Discovery Doctrine was grounded in a much older legal fiction, called terra

nullius. Originally used by lawyers in ancient Rome, this Latin legalese

refers to empty, barren or vacant territory belonging to no one. During the “Age

of Discovery,” the Catholic Church redefined terra nullius to encompass

new lands coveted by European monarchs. As the Manitoba Justice Inquiry, noted:

“terra

nullius was expanded…to include any area devoid of ‘civilized’ society. In

order to reflect colonial desires, the New World was said by some courts to fall

within this expanded definition.”27

Stretching this term’s boundaries began a litany of new crimes to enclose and

capture Aboriginals. This framing of Indigenous peoples was aptly described by

Canada’s Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, as a “restrictive

constitutional circle drawn around First Nations by the governance sections of

the Indian Act.”28

Imprisoned on Reserves

Erased

from the metaphoric map, like chalk dust from the supposed tabula rasa of

the prairies, Aboriginals were swept off the land in an ethnic-cleansing

campaign that confined them to reserves. These were Canada’s first POW

concentration camps. Corralling Indians into captivity kept them out of the way

of European settlers who were then being poured into the prairies.

Erased

from the metaphoric map, like chalk dust from the supposed tabula rasa of

the prairies, Aboriginals were swept off the land in an ethnic-cleansing

campaign that confined them to reserves. These were Canada’s first POW

concentration camps. Corralling Indians into captivity kept them out of the way

of European settlers who were then being poured into the prairies.

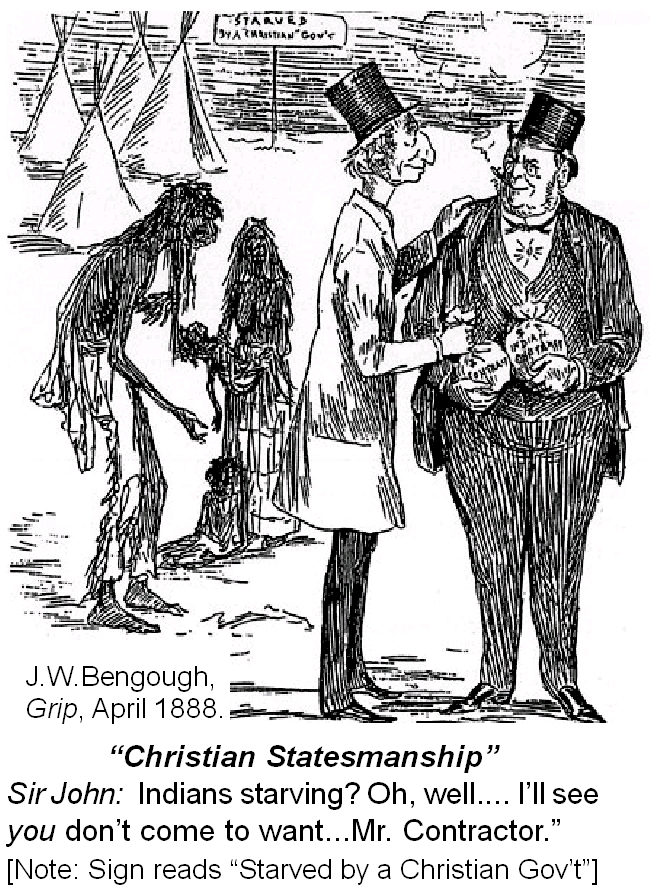

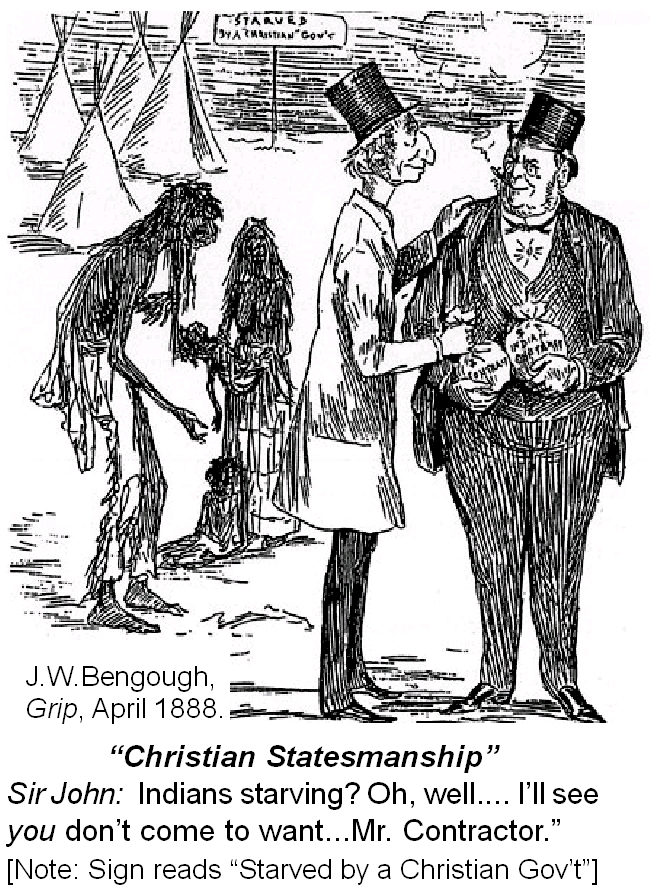

As

James Daschuk said in Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation,

and the Loss of Aboriginal Life: “Reserves became centres of incarceration

as the infamous ‘pass system’ was imposed to control movements of the treaty

population.” And, as Sir John A.MacDonald told Parliament, we “are doing all

that we can by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation,

to reduce the expense.”29

More

than a century later, the Canadian government finally admitted:

“

"The notorious pass system was never part of the formal Indian Act regime. It

began as a result of informal discussions among government officials in the

early 1880s in response to the threat that prairie Indians might forge a

pan-Indian alliance against Canadian authorities. Designed to prevent Indians on

the prairies from leaving their reserves, its immediate goal was to inhibit

their mobility. Under the system, Indians were permitted to leave their reserves

only if they had a written pass from the local Indian agent.”30

To the

Mounties, the blatant illegality of enforcing mass internment was irrelevant.

Under the Indian Act, Indians were not even allowed to hire lawyers to challenge

the Canadian government’s crimes.

Besides using the “Pass System” to arrest Indians caught “off the reservation,”

Mounties also jailed them for trespassing and for vagrancy. This was appreciated

by leading Methodist Social Gospellers like J.S.Woodsworth. In Strangers

Within Our Gates (1909), he used a five-page quotation from L.M.Fortier,

Chief Clerk of Canada’s

Immigration Department. Speaking of the Mounties, he said: “Colonizing the

North-West would be a very different matter without the aid of this splendid

organization.” Using his racist wit to lump together crooks with all Indians

found guilty of being “off reserve,” Fortier said Canada’s Mounties kept a

“sharp lookout” for “smugglers, horse thieves, criminals, wandering Indians, and

such like gentry.”31

Although racism was the norm in Woodsworth’s circles, it was opposed by

radicals, not just with words but with actions. In 1906, when local 526 of the

anarchosocialist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was formed in Vancouver,

it was led by Squamish First Nation activists. Though mostly Indigenous, this

Lumber Handlers’ union also had Chinese, Hawaiian, Anglo and Chilean members.32

Capitalism and religion were under attack by atheist radicals like Jack London.

In The Iron Heel, published one year before Woodsworth’s xenophobic

tract, London’s hero was Ernest Everhard. In arguing with a well-meaning but

naive Bishop, he said the “Indian is not so brutal and savage as the capitalist

class” and noted “The Church condones the frightful brutality and savagery with

which the capitalist class treats the working class.”

London

also quoted Presbyterian, Baptist and Methodist leaders to prove the “Church’s

outspoken defense of chattel slavery.”33

London was influenced by US Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs,34 an

atheist cofounder of the IWW. He compared the state’s control of unions with

their control of Indians. Capitalists, he said in 1906, tolerated organised

labour

“so

long, only, as it keeps within ‘proper bounds,’ but ... put [it] down summarily

the moment its members, like the remnants of Indian tribes on the western

plains, venture beyond the limits of their reservations.”35

By

keeping Indians within their “proper bounds,” Canada’s pass system contributed

to genocide on every level: physical, economic, religious, social, psychological

and political. Confinement to reserves cut off access to food and other

resources, blocked trade and commerce, stopped travel to religious and social

events, prevented the building of alliances, and stopped parents from visiting

children kidnapped and held in government-financed, church-run residential

schools.

Penned in by Education

Residential schools were seen as essential to progress. To Social-Gospel

reformers on the cutting edge of Canada’s western frontier, the “Three Cs” were

the key to teaching Indians about the culture of their superiours. As UBC

Political Science professor Barbara Arneil has said, the “driving force” behind

this education was “to foster ‘civic virtue,’ to ‘morally uplift,’ and to build

‘civilization’ through the progressive vehicle of education and the social

gospel.”36 (Emphasis added.)

While

the government and its religious agents sometimes differed on how to impose the

“Three Cs,” they collaborated well. John MacLean, a Methodist missionary in

Alberta, who became a public school inspector,37 wrote in 1899 that the

government wanted residential schools to “teach the Indians first to work and

then to pray.” MacLean however said missionaries wanted to “christianize first

and then civilize.”38 Either way, the Three-C process was genocide. While First

Nations were dispossessed of land and culture, Canada succeeded in expanding the

boundaries of the British empire. To political, economic and religious elites, it was a

win-win-win solution to the “Indian problem” that they saw as a major obstacle

to “progress.”

Whatever their differences, church and state agreed on the value of residential

schools in destroying the symbolic core of Aboriginal cultures, their languages.

MacLean became the Methodist

Church’s chief archivist and chief librarian at the Social Gospel’s Wesley

College in Winnipeg (1922-1928). (See p.26.) He said that: “It is the desire of

the Government and the missionaries that the English language should become the

only medium of communication.”39 In Canadian Savage Folk (1896),

MacLean further remarked that:

“There

can be no legitimate method of stamping out the native language except by a wise

policy of teaching English in the schools, and allowing the Indian tongue to die

out.”40

Canada’s

religious schools for Indians were a major weapon in the all-out war to

exterminate Aboriginal cultures. During the 1880s, Canada engineered a “Perfect

Storm” to wash the prairies clean of First Nations and to usher in a golden age

for European settlers. As the government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

noted in 2012:

“From

1883 onward, the federal government began funding a growing number of industrial

schools in the Canadian West. It also continued to provide regular funding to

the church-run boarding schools. The residential system grew with the country.

As Euro-Canadians settled the prairies, BC, and the North, increasing numbers of

Aboriginal children were placed in residential schools.”41

In

1884, after a report contracted by Sir John A.MacDonald, Canada began pouring

money into the Churches’ existing program of residential schools. The report,

written by Nicholas F.Davin, a poet/playwright/lawyer and newspaperman-cum-Tory

MP, urged the Canadian government to copy the assimilation plan of the US

government’s euphemistically-named “Peace Commission.” He said this US program,

“known as...‘Aggressive Civilization,” had been “amply tested” since 1869. Its

“principal feature,” he said, was the “industrial school.” The “chief thing to

attend to in dealing with the less civilized or wholly barbarous tribes,” Davin

said, “was to separate the children from the parents.”42

Another feature of “Aggressive Civilization” was the concentration and

confinement of Indians. As Davin said, “the Indians should, as far as

practicable, be consolidated on few reservations.” Canada’s Aboriginal policies

were soon dominated by mass captivity, both physically on reserves, and

culturally by church schools. Christianity was absolutely central to the

genocidal plan. Europeans, said Davin, were “civilized races whose whole

civilization…is based on religion.” Praising their “patient heroism,” he said

the “first and greatest stone in the foundation of the quasi-civilization of the

Indians ...was laid by missionaries.” Davin extolled their schools as “monuments

of religious zeal and heroic self-sacrifice.”43

After

Davin’s report on “Aggressive Civilization,” the state boosted funding to

church-run Indian schools in the western Canada from $962 in 1877, to $53,000 in

1886, and $226,000 in 1906.44 (In 2015 figures, this was $39,000, $2 million

and $5.4 million, respectively.) These church schools were cheap yet effective

bricks in the apartheid wall that kept Aboriginals out of the “Peaceable

Kingdom.”

Davin

may not have identified himself a Social Gospeller, but he did have a

“progressive” side. In 1895, he introducing a bill to allow women (white ones,

at least) to vote. Although unsuccessful, Davin’s bill sparked the only

full-fledged Commons’ debate on (white) women’s suffrage between the 1880s and

WWI.45

Davin

was influenced by his lover Kate Hayes, with whom he had a long affair and two

children. Like other Social Go-spellers in the “social purity” movement, Hayes

used religion, class and ethnicity to belittle others. She believed, said York

professor Kym Bird, that “non-Anglo-Canadians were a godless impure breed that

required assimilation and civilization into middle-class Anglo-Canadian

values.”46

These

“Canadian values” taught citizens not only to ignore the genocide of residential

schools, but to see them as proof of the Church’s benevolence towards godless

savages. But, as David Langtry, the Acting Chief Commissioner of the Canadian

Human Rights Commission stated:

“Wilful

blindness to the horrors of the schools was government policy. Dr. Peter Bryce,

hired by the...government in 1907 to report on health conditions at residential

schools in western Canada, found that in Alberta the mortality rate was a

staggering 50%.

“Ottawa’s

response was to fire Bryce, abolish the position, stop reporting and repress the

facts. Shortly afterwards, it became mandatory for all Aboriginal children to

attend residential schools.”47

Bryce

is now being celebrated by progressive Canadians for exposing the negligent, if

not deliberate, spread of TB through the schools. However, this narrative turns

a blind eye to Bryce’s overt support for cultural genocide. The “wandering bands

of Indians would still have been savages,” said Bryce in 1907, “had it not been

for the heroic devotion of those missionaries.” His report also stated that the

“story” of Canada did not sufficiently credit Europeans for “transforming the

Indian aborigines into members of a civilized society and loyal subjects of the

King.”48

Occupied and Preoccupied

First

Nations were defrauded in one of the largest land grabs in the history of

imperial civilisation. Central to this Canadian success story was a

social-engineering scheme that imposed severe limits on Aboriginal mobility,

while promoting a massive influx of European immigrants.

Newcomers, including many east Europeans, were shifted onto the prairie playing

field like so many little pawns in the “Great Game” of empire. This achieved

Canada’s nation-building goals by:

Members of Canada’s

mainstream society aided and abetted not only the genocide of Indigenous peoples

but the rapid assimilation of nonAngloSaxons. But because good, decent,

ordinary people do not generally want to collaborate in callous anti-social

enterprises, the nefarious nature of

Canada’s

imperial project had to be kept hidden. Canadians had to be convinced that their

grand national project was not only morally justified, but essential to human

progress. The narratives that evolved to rationalise and cover up Canadian

crimes, relied on the entitled sense of superiority that preoccupied

AngloProtestant thinking.

Canada’s

nation-building myths were built on the firm bedrock of religious and political

delusions. The self-image that possessed the prevailing public mindset was of a

new nation, rich not only in “Christian values” but in Britain’s hallowed,

constitutional monarchy. Accepting this mirage required a studied ignorance of

imperialism. Besides turning a blind eye to the empire’s many wars, believing in

the fictive Peaceable

Kingdom

meant blissfully ignoring the savage treatment of Indians and Canada’s

slave-like exploitation of aliens, especially nonAngloSaxons.

Out of Sight, Out of [One’s] Mind

Behind

the rich, dream-like mirage of a Heaven-on-Earth paradise that the

AngloProtestant mainstream believed they were creating in Canada, there lurked

the reality of a living hell for First Nations. Although reserves were places

of captivity, torment, deprivation and starvation, this truth was largely hidden

from mainstream Canadian consciousness. Being geographically removed from the

dominant settler society, reserves—and those trapped on them—were easy to

ignore. Other than Mounties, missionaries, and other agents of government, few

from the AngloProtestant community ever visited reservations.

So,

keeping Aboriginals confined to reserves not only facilitated European

occupation, it also swept natives under a mental rug. Keeping Indians hidden—out

of both sight and mind—helped settlers to avoid unsettling qualms of conscience.

Just seeing the living conditions of those forced onto reserves, let

alone hearing their disturbing narratives of genocide, might have upset

some settler’s blind faith in the powerful national mythology that building

Canada was a God-inspired enterprise.

Hiding

Indians on reserves shielded European settlers from the mental dis-ease that

might arise if they realised their complicity, witting or not, in Canadian

crimes against humanity. Cognitive dissonance was also avoided by non-physical

means. The physical boundary lines drawn around reserves were not as

effective in segregating Aboriginals from European settlers’ as the

storylines of superiority that separated Indians from mainstream Canada.

The official narratives of church and state created virtually insurmountable

walls of apartheid between the cultural worlds inhabited by Canada’s two main

solitudes.

First

Nations have also been held in place with linguistic weapons. Canada’s religious

and political institutions not only penned Aboriginals in place with such slurs

as “primitives,” “heathens” and “savages,” they also framed them as “strangers”

within the “Peaceable Kingdom.”

Old Narratives, New Enemies

Canada’s

largest political and religious institutions developed effective myths and

narratives to rationalise their use of structural violence against Indigenous

peoples. During the 20th century, lessons learned from the physical, social and

legal segregation of Aboriginals—and the old narratives that had evolved to

justify these diverse forms of mass captivity—were put to use against a whole

new set of enemies. With WWI and the Russian Revolution, east Europeans and

particularly “Reds” soon replaced the “Red Man” as the chosen enemy of both

church and state. New wine was placed in old bottles.

Although the “foreign”

enemy had changed, symptoms of Canada’s Settler Syndrome—that mass hysteria

which possessed mainstream AngloProtestant culture —remained intact. The racist

and xenophobic belief systems that permeated the country’s leading institutions

continued unscathed, as did the popular narratives and myths of Canadian

exceptionalism.

While the vivid, social

pathology of Canadian narcissism continued to capture the imagination of

Conservative- and Liberal-Party elites, it was also the norm within Social

Gospel circles. Even those heroic trendsetters on the vanguard of this reformist

Christian movement, like Rev. J.S.Woodsworth, were shackled and enslaved by

Canada’s national delusion.

Canada’s dominant culture believed it was their noble mission to civilise and

Christianise those seen as their inferiors. Citizens on the right, left and

centre all believed that they could not stand idly by while

Canada was besieged by Indians, east Europeans,

“Reds” or other “foreign” threats to the national good. Enslaved by narratives

of “Christian values” and west European superiority, captives of the so-called

“Peaceable Kingdom” suspended their disbelief in

Canada’s fictive myths. In doing so they were able to keep calm and carry on

imposing the audacious felonies of their self-righteous imperium.

References/Notes

17. Ibid.

18. J.S.Woodsworth,

Strangers Within Our Gates, 1909, p.194.

http://archive.org/details/strangerswithino00wooduoft

19. Rev.Thompson Ferrier,

“Indian Education in the North West,” 1906, p.40.

http://archive.org/details/indianeducationi00ferruoft

20. R.Whittington, “The

British Columbia Indian and his Future,” 1906, p.7.

21. Emery 1970, Op. cit.,

p.11.

23. Emery 1970, Op. cit.,

p.iii.

48. Bryce, Op. cit., p.7.

This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in WWI

was not the first time that thousands of people had been forced into captivity

for threatening the “peace, order and good government of Canada.”1 In fact,

Conservative and Liberal governments alike already had a well-established

modus operandi that used mass captivity to subjugate so-called “foreign”

enemies on the homefront.

WWI

was not the first time that thousands of people had been forced into captivity

for threatening the “peace, order and good government of Canada.”1 In fact,

Conservative and Liberal governments alike already had a well-established

modus operandi that used mass captivity to subjugate so-called “foreign”

enemies on the homefront.  Teaching

“The Three Cs”

Teaching

“The Three Cs” Erased

from the metaphoric map, like chalk dust from the supposed tabula rasa of

the prairies, Aboriginals were swept off the land in an ethnic-cleansing

campaign that confined them to reserves. These were Canada’s first POW

concentration camps. Corralling Indians into captivity kept them out of the way

of European settlers who were then being poured into the prairies.

Erased

from the metaphoric map, like chalk dust from the supposed tabula rasa of

the prairies, Aboriginals were swept off the land in an ethnic-cleansing

campaign that confined them to reserves. These were Canada’s first POW

concentration camps. Corralling Indians into captivity kept them out of the way

of European settlers who were then being poured into the prairies.