This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in

Captive Canada:

Renditions of the Peaceable Kingdom at War,

from Narratives of WWI and the Red Scare to the Mass Internment of Civilians

Issue #68 of

Press for Conversion (Spring 2016),

pp.30-34

Press for Conversion! is the magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).

Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this

coupon,

or use the paypal link on our webpage.

If you quote from or

use this article, please cite the source above and encourage people to

subscribe. Thanks.

Here is the pdf version of this

article as it appears in Press for Conversion!

Crushing Rebels,

Radicals and Reds:

The Bunker Mentality, All in the Woodsworth Family Tradition

By

Richard Sanders, Coordinator,

Coalition to

Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT)

James Shaver (J.S.) Woodsworth’s

racist nativism was typical of his class and heritage. By artfully expressing

and justifying the biases of Canadian culture, he captured the support of many

progressives. His was a compassionate elitism, deeply rooted in a religious and

political faith that preached love and loathing for those who were scorned as

inferiour.

Although J.S.Woodsworth was a patronising ethnocentric xenophobe, at least he

came by it honestly. His mother and father both came from prestigious lineages

that were deeply ensconced in the traditions of Anglo-Saxon superiority. The

particularly virulent form of cultural narcissism that was passed down to him,

promoted class loyalties to conserve the ancient powers of both church and

state.

The Shavers

The Shavers

J.S.Woodsworth’s middle name, Shaver, is the anglicised version of his mother’s

maiden name, Schaeffer, meaning “shepherd.” His mother, Josephine Shaver, was

descended from Wilhelm Schaeffer, who came from Germany to the US in the 1700s.

His son, John Shaver, was a loyal supporter of the British empire and fought with either the King’s Royal Regiment of

New York,1 or Butler’s Rangers, a loyalist

regiment. After the empire loyalists were defeated in the American revolution,

John Shaver fled to Upper Canada’s

Niagara region where he soon received a large grant of land from the colonial

government.

John’s

son William became an affluent farmer with “patriarchal habits and demeanor.”

Amassing 1,600 acres, he was “one step below the ‘squirearchy’ on the social

ladder.” As an “exemplary” Wesleyan,2

he welcomed local Methodists to meet in his home and he willed enough

land and money to build a new church.3

In

1830, William’s son Peter, at the tender age of 21, was able to buy a 100-acre

farm called Applewood, in what is now downtown Etobicoke, in Toronto’s west end.

The local historical society says “it is believed Peter was a magistrate for the

Home District in 1843.”4

On July 14, 1843, the Governor of Upper Canada appointed Peter Shaver as

magistrate for this district,5

which included all of what is now greater Toronto. Untrained in law,

these Justices of the Peace were a law unto themselves. They “set tax rates,

appointed county officials, paid salaries, enforced local regulations, held

court,” and “were, in effect, the local...government.”6

As

Tories, magistrates were loyal servants of the corrupt Family Compact which

dominated the social, political and economic life of Upper Canada. As such,

they were thoroughly despised by such rabble-rousers as William Lyon Mackenzie,

leader of the 1837-1838 uprising. In 1833, he wrote that Magistrates “are

frequently proved guilty of the most criminal outrages against the peace

of the community” and “are encouraged in their disgraceful career—advanced and

promoted to places of greater power and trust.”7

During

the Upper Canada Rebellion, over 400 radicals were arrested and charged with

insurrection and/or treason in the Home District alone.8

In sentencing, Magistrates mixed politics with absurd religious beliefs.

Charges against Home-District rebels said they did not have “the fear of God” in

their “heart but...[were] moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil.”9

This old chestnut was thrown at Louis Riel almost five decades later.10

None

would dare impute such charges against devout Methodists like the Shavers.

Peter and his brother George were trustees of Etobicoke’s first Methodist

church.11 Peter also

allowed a young Methodist circuit rider to board at his farm. This is how

Peter’s daughter Josephine met a certain, young “saddle-bag” preacher named

James Woodsworth. They married in 1868 and their first child, J.S.Woodsworth,

was born at the Applewood estate in 1874.12 He

grew up there, a captive of the Loyalist myths and religious narratives spun by

both parents and their families.

James

Woodsworth Sr.

James

Woodsworth Sr.

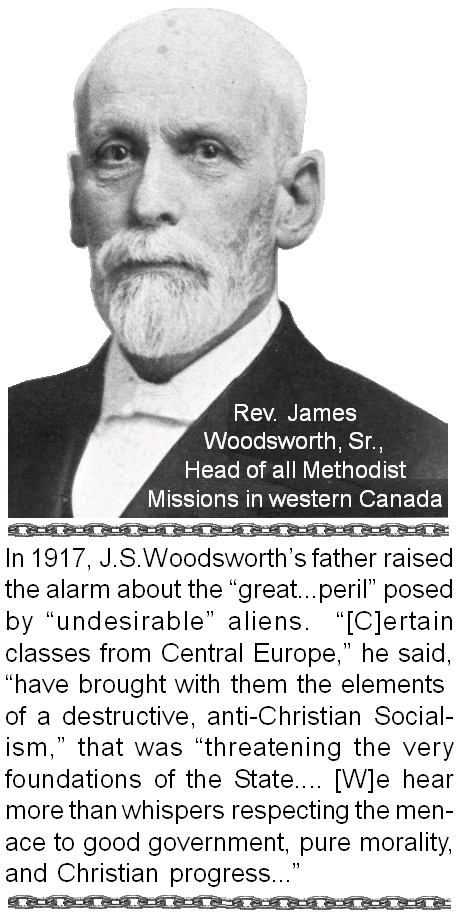

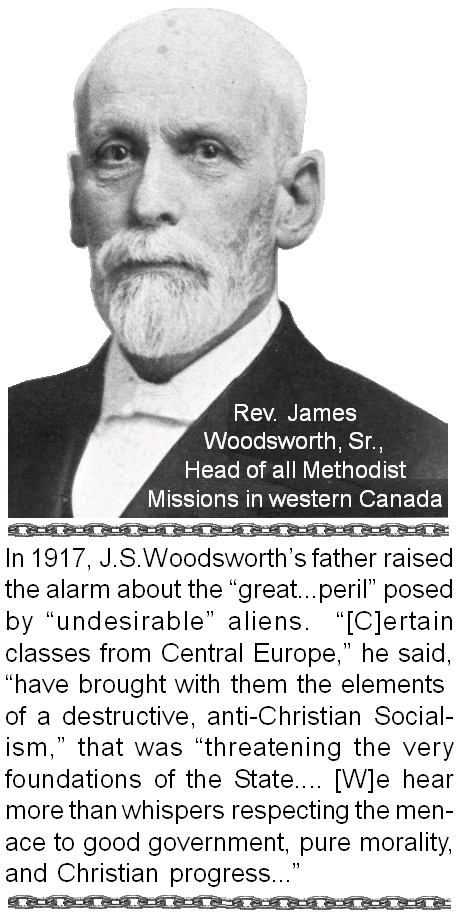

Rev. James Woodsworth Sr. had a powerful

influence on the beliefs of his namesake. In fact, James Jr. was groomed from an

early age to follow in his father’s footsteps and to become a Methodist

minister. After leading flocks in various Ontario churches, James Sr. was

honoured to became the Superintendent of Methodist Missions for Canada’s four

western provinces. This made him a shepherd of shepherds, responsible for

guiding Methodist efforts to aid the expansion of Britain’s empire across the

west. Holding this influential position for thirty years (1885-1915) made him

“an enormously important figure in the history of the Canadian West.”13

James Sr’s autobiography proudly described the

Methodist church’s role in converting native peoples, who he vilified with

epithets like “heathens” and “savage people.” His crusade to shepherd

missionaries began in what he called the “troublous times” of the Northwest

Rebellion. He reported how “very gratifying” it was, “especially to the

Methodist Church, that the Indians under her care were united in their loyalty to Queen

and country.”14

In describing the insurrection of 1885, James

Sr. turned a blind eye to its real causes. Instead, his simple-minded, racist

narrative laid all blame on the supposed propensity of Aboriginals to rely on

senseless violence. “Many Indians and half-breeds,” said James Sr., “took to the

warpath and attacked the whites.” Then, invoking sympathy for Canadian troops

who faced such “great difficulty” and “much hardship” when crushing the Indian

rebellion, he noted that “[m]any lives were lost in this unfortunate

disturbance.” But, he said, on “the other hand, much good resulted.” To

J.S.Woodsworth’s father, the loss of lives was “good” because

"disaffected half-breeds and rebellious Indians were taught a salutary lesson;

they learned something of the strength of British rule, and likewise experienced

something of its clemency and righteousness.”15

Canada’s ruthless military suppression of the

uprising had other “salutary” results, he said. The “penetration of so many

soldiers from the East into the heart of this great country served to advertise

its resources.” When soldiers settled there, it meant “the North-West became

better known and more highly appreciated.”16

The 1885 insurrection against Canada’s genocidal

repression, land plunder and forced concentration of Indigenous peoples onto

reservations, pitted Métis and Cree-Assiniboine First Nations not only against

the imperial forces of Canadian troops and mounted police, but also against

powerful civil-society institutions. Chief among these was the Methodist Church.

James

Sr. also held extremely negative views of nonAnglos, especially Ukrainians.

These prejudices were based in part on his extremist religious beliefs. In his

1917 memoirs, James Sr. warned that their “evil effects” were spreading.

Ukrainians, he said, were “almost...destitute of any provision for their

religious and spiritual training. The evil effects of this state of things are

already being felt by other people in the vicinity.”17

J.S.Woodsworth was greatly influenced by his

father’s righteous bigotry, especially towards aboriginals, Blacks and

Ukrainians. This fact is noted in biographer Kenneth McNaught’s classic A

Prophet in Politics, which commented on

"the

extent to which the nativism of the father had successfully rubbed off on the

son. Although he would later moderate his views, J.S.Woodsworth never completely

shed his early awkwardness and insensitivity towards blacks and Indians, and

later, eastern Europeans. His stories...reveal a popular attitude at the time,

that Indians were sinister, alien, and violent.”18

Similarly, Allen Mills’ biography notes that “in

his early beliefs, James Shaver Woodsworth was very much the son of his father.”

Mills, a political scientist at the University of Winnipeg, observed that “Clearly the germ of the social gospel as well as the

nativism of J.S. Woodsworth derived from his father.”19

This influence between generations seems to have

flowed both ways. J.S. Woodsworth was, for example, responsible for the “final

edit” of his father’s autobiography in 1917. Mills says that J.S. “claimed to

have altered” his father’s book “in ways that he believed improved it.”20

A core xenophobic belief shared by both father

and son, was that Canada’s role as a beacon of Christian civilisation was

threatened by the rapid influx of “undesirables.” These “strangers” could not,

or would not, be assimilated fast enough. In discussing the flood of aliens

entering Canada’s gates, James Sr. warned that:

"Christian people should watch this great movement, lest peoples of various

nationalities, with various and conflicting moral and religious beliefs, and

social sentiments, should come more rapidly than true assimilation can take

place.”21

J.S.Woodsworth’s father saw Canada’s

nation-building project as fundamentally religious. Canada, he said, is

"a

nation whose foundations are laid in righteousness, whose people are the Lord’s,

and whose pre-eminence because of righteous principles and conduct will ensure

its prosperity and long-continued existence.”22

In sounding the alarm about aliens, James the

elder told terrifying tales of “certain classes from Central Europe” who:

"have

brought with them the elements of a destructive, anti-Christian Socialism,

whose presence and operation are threatening the very foundations of the

State. This is recognised as so great a peril that the authorities at Washington

are taking steps to limit immigration, hoping to at least reduce the percentage

of these undesirables. The streams of immigration which during the last

century have been so freely flowing into the neighboring Republic have set

towards our fair land, and we shall soon be confronted with problems similar to

those which so far have baffled the wisdom and skill of our sister nation.

Already we hear more than whispers respecting the menace to good government,

pure morality, and Christian progress which exists in what is acknowledged

to be the unassimilated elements....”23 (Emphasis

added.)

James

Sr’s fear of a “destructive, anti-Christian Socialism” that was “threatening

the very foundations of the State,” was also of grave concern to his son,

J.S. But where did James Sr. acquire such a virulent animosity towards those

who dared present a “menace to good government”? To answer this, we need

to look back yet another generation to the powerful influence of James Sr’s

father.

Richard

Woodsworth

Richard

Woodsworth

In

1830, J.S.Woodsworth’s paternal grandfather, Richard Wood, changed his name to

Woodsworth and emigrated from Yorkshire

England to York,24 the

colonial capital of Upper Canada. Although never ordained—like his sons James

and Richard W., and James’ son J.S.—Richard became well-known as a leader and

lay minister in the Wesleyan Methodist church. An 1899 history of Toronto

Methodism said of Richard Woodsworth that: “no man in the George Street church

was more highly respected or wielded a greater influence.”

And, Richard was listed first in this church’s “noble army of local

preachers, class and prayer leaders.”25

In the

late 1830s, when York’s Methodists split over the struggle between

Reformers and Upper Canada’s

elitist Family Compact, Richard remained a “staunch loyalist.” He supported the

colony’s Governor and backed the British Wesleyan church. Meanwhile, the

independent Methodist Episcopal Church joined forces with the Reformers. As

McNaught noted, “Richard received a sword to assist in the defence of [Governor]

Sir Francis Bond Head.”26

On this, Mills remarked that

"his

grandfather’s sword, raised in anger in 1837 against William Lyon Mackenzie’s

insurrection, was later prominently displayed on the wall of his [J.S.

Woodsworth’s] home in Winnipeg.”27

Richard’s sword was given to him so that he would help suppress the uprising

against Lt.Gov. Sir Francis Bond Head, a British Army veteran (1811-1825) who

began ruling Upper Canada in 1836. Soon after arriving from England, Head dissolved

Parliament and called an election.28

Backed by the colonial elite and wealthy empire loyalists”—like the Shavers, and

the Woodsworths of the Wesleyan Methodist church—Head faced reformers and rebels

who demanded “responsible government.” They opposed the Family Compact’s system

of patronage which allied bankers, businessmen, politicians and corrupt

officials, with the state’s repressive forces of “law and order.” To fight the

rebels, Bond’s troops handed out weapons to vigilants who remained fiercely

loyal to the Empire and its corrupt local elite.

In

their biographies of J.S.Woodsworth, neither Mills nor McNaught shed much light

on Richard’s loyalist sword. For details we must turn to the earliest records of

a Loyalist force called the British American Fire Co. (BAFC). Its records show

that in April 1837, Richard Woodsworth became the BAFC’s “First Lieutenant.”29 This

fire brigade was backed by about fifty of York’s most prominent men, including

Family Compact leaders Archdeacon John Strachan, John Elmsley, Jr. and William

Allan. The latter, who governed the BAFC, was a banker, businessman and Tory

official who has been called “the financial genius of the ruling Family

Compact,...one of the two or three richest men in the province,”30 and

“the unquestioned doyen of Upper Canadian business.”31

It is

no wonder then that Richard Woodsworth, and others in the Loyalist BAFC, vowed

to help crush the uprising. On December 5, 1837, “the city was alarmed by the

ringing of the fire bell” which warned that the rebels were approaching. The

brigade’s records report its unanimous resolve “to take up arms as an

independent volunteer company to resist the attempt of traitors and rebels to

invade our rights and disturb our peace.”32

Like

other Empire Loyalists eager to take up arms to protect the Family Compact, the

BAFC gathered at City Hall. It was there, at the start of the Rebellion, that

James Ashfield, a gunsmith like his father, had “the duty of putting in order

and serving out to the volunteers the muskets and small arms.”33 “Fighting

Tory” Richard Woodsworth may have received his sword from Ashfield, who became

the Fire Brigade chief, a City Councillor and leader of the Orange Lodge (a

Masonic-style order of AngloProtestant supremacists).

BAFC

minutes show that Richard Woodsworth was active throughout the rebellion, moving

and seconding motions and, no doubt, taking part in company duties which

included “patrolling the streets... [to] arrest suspicious persons.” When

700-800 rebels approached, the BAFC was “ordered...to give them a warm

reception” and “with great spirit” they did, “most of them with muskets in their

hands.”34

Woodsworth’s closest comrades in arms within the BAFC brigade were Alexander

Hamilton and Thomas Storm. All three were prominent in York’s building trade. In

1840, these three Loyalists were rewarded with “a contract for the erection of

the new garrison,”35 New

Fort York. The old fort was the base used to quell the rebels. (Later, during

WWI, the fort’s Barracks—built by Woodsworth et al—were used to intern

the Germans and Ukrainians being sent to forced labour camps.36)

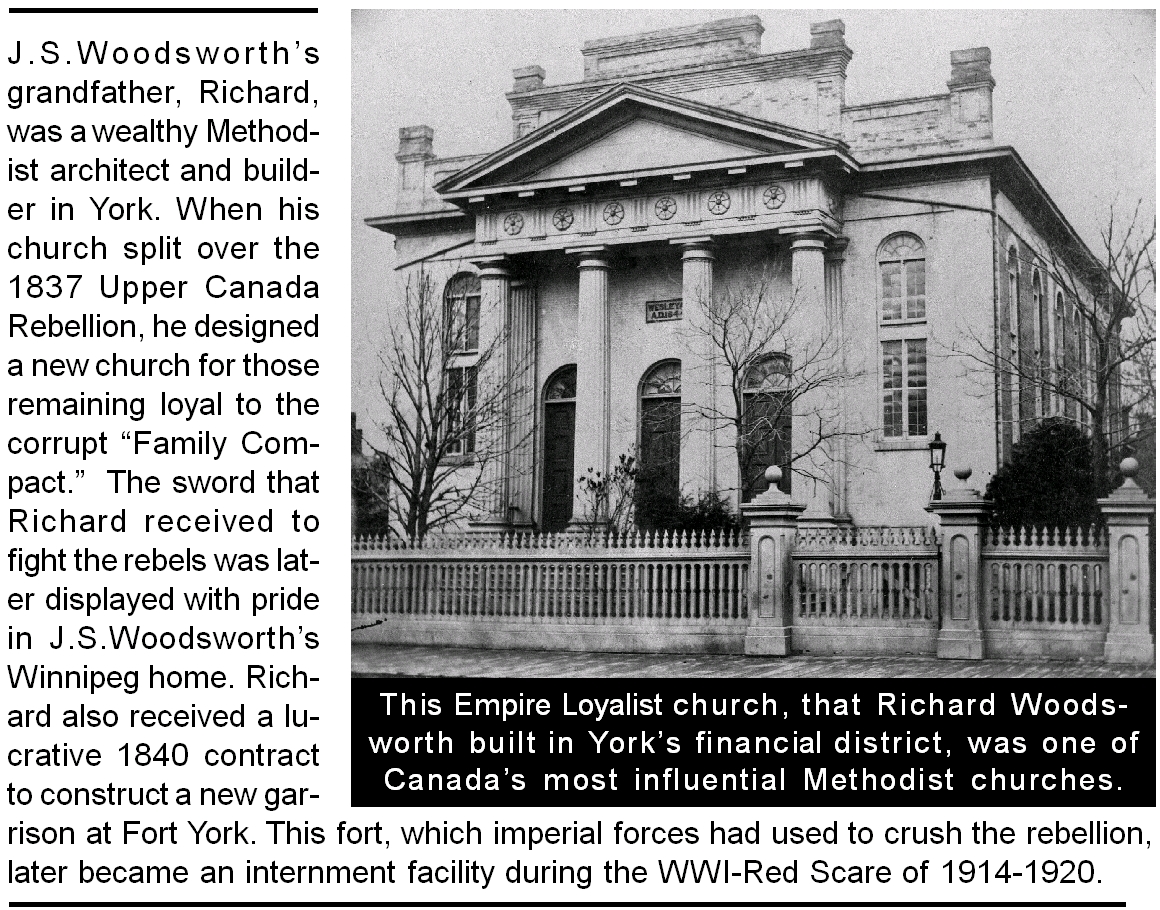

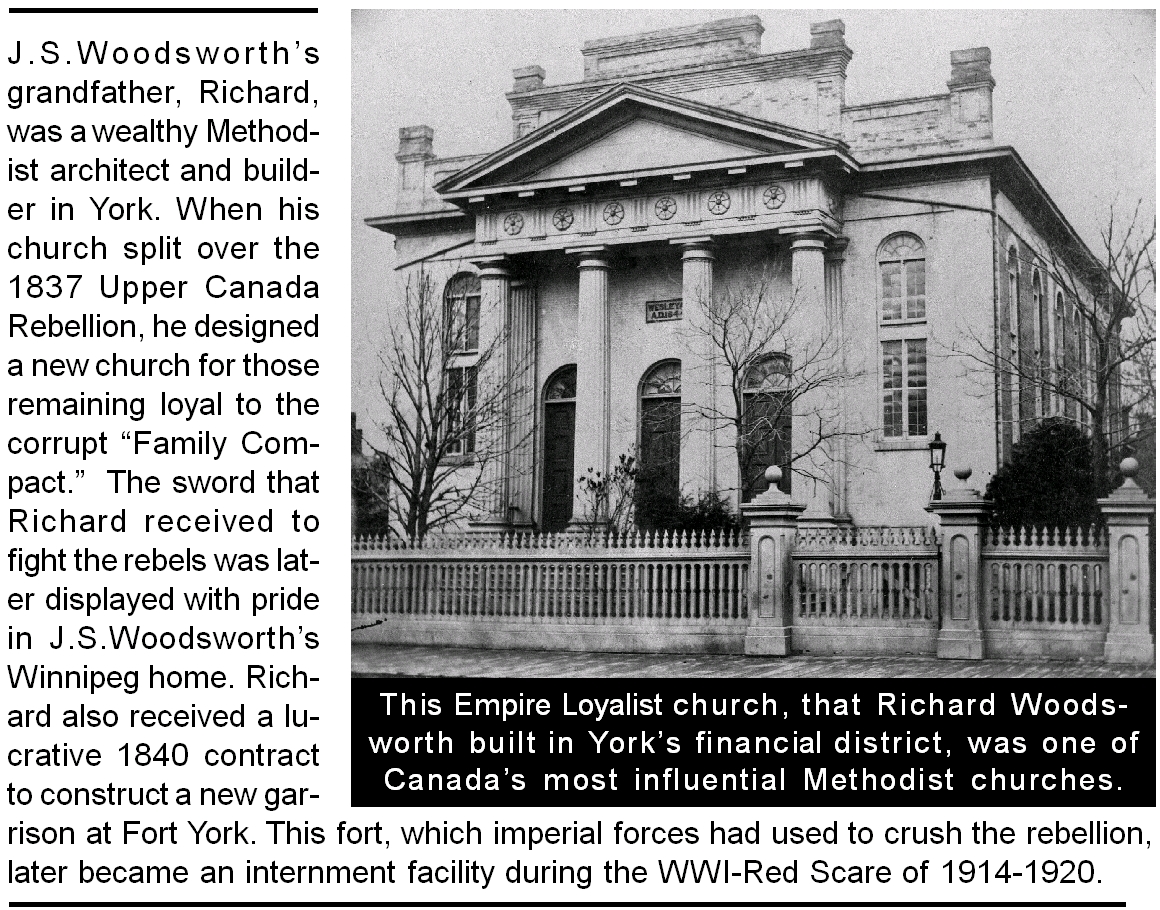

Woodsworth, Storm and Hamilton were also all prominent members in the same

church. When the Methodists were irreconcilably split over the rebellion,

Richard designed and built the new Richmond St. church in York (Toronto) for the

Loyalist Wesleyan faction.37 Erected

in 1844, in the financial district, it was perhaps “the largest and most

influential Wesleyan Methodist church in Canada.”38

J.S.: The Anti-Marxist Socialist

Like

his mother’s and father’s loyalist forebears, J.S.Woodsworth helped to quel the

rise of rebellious radicals. In the years leading up to WWI, Woodsworth used

his status as a rising star of the Social Gospel to shepherd public opinion

about the supposed danger that certain immigrants posed to Canada’s Christian

civilisation. His fear-filled musings about unassimilable aliens targeted east

Europeans, who were the bogeyman of choice among Canada’s political, corporate

and religious elites.

During Russia’s 1917 revolution, Woodsworth finished his government report on

Ukrainian Rural Communities. Its conclusion, “The Ukrainian as seen by

Canadian Protestant Missionaries,” quoted Methodist missionaries who were trying

to convert Ukrainians in northern Alberta. The first of these epistles, by

Rev.C.H. Lawford, warned of a looming menace. “The great danger,” he said, “is

that these people, in their efforts for ‘freedom’ will drift into Socialism, for

socialistic literature is coming into every settlement.”39 Lawford

used this threat to request more Methodist tracts for distribution to Ukrainians

falling prey to dreaded “Socialism.”

Historian George Emery noted that “Methodist hostility to socialism... confirmed

labour and socialist spokesmen in the opinion that the church was the adjunct of

the monied classes.” Some churchmen saw “socialism as part of the un-Canadian

cultural baggage which the foreign immigrant imported from his European

background” and which should “be eliminated in the course of...assimilation.”40

By

using Lawford’s letter, Woodsworth betrayed his own biases. Both men had

graduated in 1896 from the Methodist Church’s Wesley College, Canada’s centre

for training in the Social Gospel. (See pp.26-28.) Emery said Lawford “seemed

unable to surmount a personal dislike for the Ukrainians.” Lawford said he

feared they might have “a most baneful influence on our nation throughout.”41 Emery

outlined Lawford’s efforts to use Methodism to convert, and free, Ukrainians

from their Catholic and Orthodox faiths. Lawford disliked Ukrainian priests

saying they exerted a bondage over their flocks that was “worse than any African

slavery.”42

Woodsworth’s report on Ukrainians, included a 1911 letter from Rev.W.H. Pike

who, like Woodsworth, had graduated from the Methodist’s Victoria College in

Toronto.43 Pike’s letter

said he entered an Edmonton dance hall to gather intelligence on Ukrainian youth

culture. In describing a man there, Pike says he “led him on to tell me of

their ideas and ideals.” Pike described the youth’s “desire for a life of

freedom from priest-craft, from shallowness and hypocrisy, from fear of

purgatory and divine wrath.” Methodists like Pike and Woodsworth shared this

young man’s critique of Ukrainian churches. However, they were even more irked

when young Ukrainians—like this dance-hall youth—embraced atheist socialism by

saying that:

"we

have come to Canada and we are going to be free; it’s a free country and we are

not going to be slaves of priests or pope or church.... The best thing for us is

socialism.”44

In

Five Missionary Minutes (1912), Pike voiced his fear of Ukrainian

socialists. “How are we going to deal with the type of Socialism we find among

these people?” he asked. “It is a mixture of socialism, infidelity, and

Christianity. They have a false idea of freedom and throw off all religious

restraint.”45 (J.S. said

he was “indebted” to Pike “for assisting in the intensive study of farms in

selected districts.”46)

Woodsworth’s virulent contempt for Marxism, and for the atheist strain of

socialism, was an ideology he shared with Canada’s political, corporate and

religious elites. He was, “of course... [an] anti-Marxist and anti-Communist,”47 who

defined his politics “in contradistinction to Marxism,” said Mills. “At the

bottom of his quarrel with Marxism was a disagreement over the nature of

economic class.”48

Woodsworth was hostile to the Marxist narrative that social change is won

through “class struggle.” To Woodsworth, success came by finding common ground

with one’s adversaries. Although he always pushed for cooperation between rival

classes, like workers and bosses, he refused to allow any cooperation with

Marxist socialists. He even opposed forming a “common front” with them against

Fascism.

Just

as Woodsworth derided Marx-ist narratives, communists spent decades criticising

his compromising brand of bourgeois socialism. In 1919, an activist with BC’s

radical Socialist Party called his theories “consummate twaddle.”49 A

decade later, the Communist Party (CP) labelled him a “Pacifist Flunkey of the

Ruling Class.”50 In 1932,

renowned Canadian poet Dorothy Livesay echoed the CP narrative that his

watered-down, “pink” socialism made bedfellows of “Capital and Labor.”51

In

1934, Woodsworth dissolved the Ontario CCF for cooperating with the Canadian

Labour Defence League (CLDL).52 With

350 branches and 17,000 members by 1933, the CLDL defended militant unionists in

court. It also collected 459,000 signatures to repeal Section 98, a repressive

law used to intern radicals, including leaders of the CP.53

(See pp.42, 45.)

While

some Woodsworth fans are inspired by Marxist ideals, Mills said this shows how

“myth can embroider reality, for Woodsworth was, of course, a militant

anti-Marxist.”54

“Discovering the ‘real’ Woodsworth requires putting aside myth,” said Mills, to

get “beyond the hagiography which masquerades as biography.”55

Mills’ own book on Woodsworth is a case in

point. He used much sophistry to argue that Woodsworth was not a racist.56

In 1999, another biographer, McNaught, said that

in his 1959 biography of Woodsworth: “I did err in glossing over some frailties

in Woodsworth. He was..., by today’s judgement, a racist....”57

Confined by

Hero Myths

In his

2013 MA thesis on the “Myth and the Reality” of J.S.Woodsworth, Eric MacDonald

described how biographers selected “different historical events to gloss over

and misrepresent in order to cast Woodsworth as an even greater hero.” Because

each writer crafted “a more compelling character for the period, and a more

captivating story,” the

Woodsworth “mythology has placed the narrative above... historical accuracy.”

Narratives about Woodsworth, said MacDonald, “created the impression of a

messianic character, who represented all the hopes and ideals of the nascent

Canadian political left.”

This “admiration” for Woodsworth, he said, “morphed into exultation and

exaggeration.”58

Biographers have been among the most important information gatekeepers of the

Woodsworth hero cult. This cult uses the Woodsworth brand to create a group

identity for progressives in the CCF-NDP tradition. The success of this

mythmaking has required that adherents ignore Woodsworth’s flaws, and also

overlook any positive features of his radical socialist rivals.

In

discussing the core of Woodsworth’s longstanding opposition to Marxism, Mills

made this observation:

"He

did not hold that human beings were captives of their class status or

historical conditions.... (Woodsworth probably believed that, since he had

extricated himself from the professional middle class, his own life was

an illustration of this principle.)”59 (Emphasis

added.)

While some people are able to free

themselves from the shackles of their religious, political and class biases,

Woodsworth’s success in this personal struggle is debatable. And, it is

certainly far from clear that Woodsworth ever “extricated himself from the

professional middle class,” as claimed. Neither is it clear that he was able

to fully escape the outdated delusions of AngloProtestant superiourity that had

secured his forebears’ loyalty to successive Canadian elites. One certainty

however is that Woodsworth did remain a loyal, lifelong captive of the

fervent, antiRed phobia that has long informed a diverse array of Canadian

political and religious narratives, from those employed by the radical right to

the those of the progressive left.

59. Mills, Op. cit.,

p.77.

The Next Generation:

Charles Woodsworth, Our Man in Saigon

By Richard Sanders

In exploring the Woodsworth

family tradition of cooperating with empire, it is worth examining the career

J.S.Woodsworth’s oldest son. Born in 1909, Charles grew up to be editor-in-chief

of the Ottawa Citizen (1948-1955). But besides being the paper’s key

gatekeeper, he also made it into the news.

In 1949, after the ethnic cleansing of 957,000

Palestinians from their homeland,1 Woodsworth

went to Israel. He praised it as a “democratic” and “progressive socialist

state” leading “a social revolution...long overdue in the Middle East,” which he

called “one of the most backward areas in the world.”

Israel, he said, “could not afford” to “absorb the 250,000 Arab

refugees...inside her borders.”2

He praised heavily-fortified kibbutzim that, “like stockade[s]

against Red Indians,... guard colonizers and defend Jewish homeland against

enemies.”3

Woodsworth was a Cold Warrior. In 1952, he told

the Canadian Citizenship Council (CCC): “Let us not try to minimize the dangers

of Communism.... Let us see it for the reactionary and brutal thing it is.”4

During the 1950s and 1960s, the CCC was an agency of assimilation funded

by the government’s right-wing, Citizenship Branch. (The Branch sought “the

integration of new immigrants, ethnic minorities, and Indians.”5

See p.47.)

Charles soon became a diplomat. After a posting

to the US (1956-1960), he became Canada’s point man on the International

Commission for Supervision and Control (ICSC) in Saigon (1960-1961).6

In Quiet Complicity: Canadian Involvement in the Vietnam War, Victor

Levant said Canada’s role on the ICSC was “characterised by partisan voting,

wilful distortion of fact, and complicity in US violations of both the Geneva

and Paris agreements.”7 Woodsworth’s

duplicity in this charade was revealed by the US Ambassador to Saigon in a secret cable describing Woodsworth’s detailed suggestions on how US

troops and war materials should be smuggled into

Vietnam without alerting the international

commission overseeing the ceasefire.8

Charles Woodsworth later served Canada as

ambassador to South Africa, Ethiopia, Somalia and Madagascar.

8. Frederick Nolting Cable,

June 21, 1961. Cited by Levant, Ibid., pp.156-157.

This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in

James

Woodsworth Sr.

James

Woodsworth Sr. Richard

Woodsworth

Richard

Woodsworth