This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in

Captive Canada:

Renditions of the Peaceable Kingdom at War,

from Narratives of WWI and the Red Scare to the Mass Internment of Civilians

Issue #68 of

Press for Conversion (Spring 2016),

pp.36-38.

Press for Conversion! is the magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).

Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this

coupon,

or use the paypal link on our webpage.

If you quote from or

use this article, please cite the source above and encourage people to

subscribe. Thanks.

Here is the pdf version of this

article as it appears in Press for Conversion!

Canadian antiSemites, antiReds and the Internment of Trotsky

By Richard Sanders, Coordinator,

Coalition to

Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT)

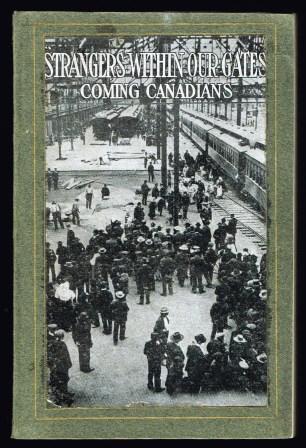

In Strangers Within our Gates (1909),

J.S.Woodsworth revealed his contempt for east Europeans, Aboriginals, Asians and

Blacks. However, he had a slightly higher regard for Jewish immigrants, in large

part because he saw a better chance of assimilating them.

In Strangers Within our Gates (1909),

J.S.Woodsworth revealed his contempt for east Europeans, Aboriginals, Asians and

Blacks. However, he had a slightly higher regard for Jewish immigrants, in large

part because he saw a better chance of assimilating them.

Labelling all “Hebrews” as “[n]aturally

religious,...industrious and ambitious,” Woodsworth concluded “the Jew is bound

to succeed.” Then, saying “they may be miserly along some lines,” he branded

all Jewish people as having “keen business instincts,” from the “pedlars or

sweat-shop tailors to the money-barons who control the world’s finances.”1

After explaining that young Jewish newcomers to

Canada were “drifting away from the Synagogues,” Woodsworth sadly noted the

disturbing fact that “they are not becoming Christians, but atheists or

secularists.”

He then concluded his section on “Hebrews”

by saying that the “most serious danger” faced by “our immigrants,” is “the loss

of old faith in the new land.”2

Woodsworth made no secret of his view that this

vulnerability among Jewish immigrants was an opportunity that Christians should

exploit. In his chapter, “A Challenge to the Church,” he used anecdotes about

Hebrew children straying from Judaism, “to plead the cause of Jewish missions.”

Stating that the “old faith is lost,” he asked: “Have we a better to offer?

Then, can we refuse to make the Jews sharers of our Gospel liberty?”3

His answer lies in stories promoting church efforts to convert Jews who had

wandered from their faith.

Woodsworth gave praise to the “London Society for

Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews” for its missionary work in Montreal and Ottawa. He also

blessed Presbyterian and Anglican Churchs’ efforts to convert Jews in Toronto

and Winnipeg. In advertising the Methodist Mission in Winnipeg, of which he was

then Superintendent, Woodsworth rejoiced that “Russian-Jewish children are

taking an active interest in the Sunday School.”4

English professor Terrence Craig compared “racial

attitudes” in Woodsworth’s “pseudosociological” work with those in Rev.Charles

Gordon’s novel, The Foreigner. Calling the latter “a fictionalised

version of Strangers Within our Gates,” he noted that while Woodsworth

“deplored...Jewish middlemen acting dishonestly as

interpreters and business agents for less educated immigrants, the villain in

The Foreigner is such a character. Rosenblatt, a greedy, conniving, and

immoral Jew, is the antithesis of the Christian missionaries. He exploits the

simple Galician [Ukrainian] community in Winnipeg both financially and

immorally.”5

Craig also explained that:

“For Gordon and Woodsworth..., the idea of Jews being

God’s chosen people contradicted their own claim for predestined Anglo-Saxon

superiority in Canada.... Theirs was a narrow national ...and unhistorical view,

so ethnically egotistic that racism was its inevitable result.... [I]t was

popularly believed that Jewish immigrants would ...compete in business with the

WASP entrepreneurial superstructure.”6

Canada’s rabid anti-Semitism and the widespread

prejudice against east Europeans went hand in political hand. Jews and Slavs

were often tarred as seditious, leftwing radicals. Woodsworth not only linked

east Europeans with Judaism, but with an atheist brand of socialism that went

far beyond the accepted, religious pale:

“Many of our immigrants from Russia and Roumania are

Socialists, some of them of the most extreme type. This seems rather

strange, as naturally the Jew is individualistic.... Socialism has

come as a gospel, and they have welcomed it with almost religious devotion.

Some of them have preached anarchy.”7

(Emphasis added.)

Woodsworth was suggesting that “extreme”

Socialism, which replaced “religious devotion” with a political “gospel,”

threatened the Canadian establishment. He devoted his life to crafting Social

Gospel politics as an acceptable alternative. Christian social democrats were

tolerable to the establishment because they rejected the atheist, anticapitalist

Socialism attributed to radicalised Jews and east Europeans. Compared to these

“extremists,” Woodsworth’s middle-of-the-road socialism was tame, loyal,

compliant and easily co-opted.

Blaming “extreme” socialism on “despair”

caused by “intolerable conditions” abroad, Woodsworth believed that better

conditions in Canada meant that “extremists cannot secure a large following.”8

His narrative did not mention the Czar’s

use of extreme violence, including mass murder, to crush general strikes

and mass protests for democracy. Nor did Woodsworth note that the Czar had

forced hundreds of thousands into internment. (See

“The Russian Revolution of

1905-1907,”

pp.38-39.) Instead, Woodsworth’s worries dovetailed nicely with the paranoid

antiRed delusions of the Canadian elite. They shared an intense phobia that

godless, east European socialist fanatics were threatening the established

social, religious and political order of our so-called Peaceable Kingdom.

Jewish Socialists in Revolt

In the 20th century’s first decade, the imperial

Christian rulers of Britain, Russia, Germany and Austria—besides being an

intermarried racist elite—all faced a common threat from popular socialist

uprisings. Jewish socialists were active in all of these multiethnic movements.

The Bund for example, which began in 1897, was a militant Jewish trade union and

political party in Russia. Between 1903 and 1905, Bundists organised “a

succession of strikes in factories, in railways, in sweatshops and textile

mills”

and in one summer alone, 4,500 of them

were arrested.9

Russia’s reactionary backlash included state

repression of the Left and deadly antiSemitic rampages. Between 1903 and 1906,

2,500 Jews were killed in Odessa Ukraine alone. In the worst Ukrainian pogrom of

1905, 400 to 800 were killed when blamed for a general strike.10

After the Czar crushed the Bund and other

socialist groups, “many Jewish radicals fled to North America...[and] both

secularists and radicals became a driving force in the life of North American

Jewry.”11

In 1906, while radicals—Jewish and otherwise—were

being killed, exiled or interned by Czarist forces, a Conservative MP presented

Canada’s Parliament with a resolution denouncing Russia’s “reign of terror.” It

stated that “large numbers of helpless men, women and children of the Hebrew

race were massacred in a most brutal and inhuman manner.” While saying the

murder of 100,000 Hebrews was “a disgrace to...civilization,”12 the

resolution did not mention the mass killing and internment of those who were not

Jewish. It also failed to mention the huge strikes and protests that were then

threatening to topple the Czar’s brutal regime.

After uttering a few niceties, Liberal Prime

Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier spoke out against the idea of even debating the

motion. Conservative Sir Robert Borden agreed, as did Liberal Quebec

nationalist, Henri Bourassa, who argued:

After uttering a few niceties, Liberal Prime

Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier spoke out against the idea of even debating the

motion. Conservative Sir Robert Borden agreed, as did Liberal Quebec

nationalist, Henri Bourassa, who argued:

“[S]o far as Russian Jews are concerned, perhaps we might

be a little careful about our expressions of sympathy, in view of the well

established fact...that the Jews have been at the bottom of most of the social

troubles that have risen in Russia—that a great deal of the money that has been

raised...on behalf of the Russian Jews has been used...in purchasing firearms

and supplies for the revolutionists.”

Bourassa added that it would be

“embarrassing for the British government ...if

we...express[ed] sympathy for people who, having taken a large share in the

revolution in Russia, are now... sufferers from that revolution.”13

Official Canadian criticism

of the Csar’s mass murder of Jews would have been especially “embarrassing

for the British government” because Czar Nicholas II [pictured on left] was the first cousin of

King George V [pictured on right]. And, Canada’s then-Governor General, Prince Arthur, who passed

laws by decree with Borden’s Cabinet, was a son of Queen Victoria. Also, both Czar Nicholas II and Queen Victoria were both descended from Britain’s King

George II, a German.

Bourassa supported the Christian killing of Jews by

saying “the Jews had prepared a conspiracy to slaughter the Christians.” No MPs

countered his narrative to excuse the mass murder of Russian Jews. Neither did

MPs criticise the Czar’s regime for quelling protests and strikes by killing

thousands and interning hundreds of thousands more. Russian “Reds,” like the

“Reds” in Canada or anywhere else, were the diabolical enemies of empire.

Canadian Liberals and Conservatives, would not deign to embarrass British

authorities by issuing resolutions denouncing the slaughter and imprisonment of

anti-imperialist “Reds,” especially Jewish ones.

The Canadian elite’s burgeoning opposition to

radicals found loyal support in the Social Gospel. By 1909, when Canada faced

the nascent stirrings of its first Red Scare, right-wing bigotry was at home in

the pages of reformist Christian literature, from Rev. Woodsworth’s missionary

diatribes to Rev. Gordon’s populist novels. The Canadian public’s growing

distrust of east Europeans and Jews—spurred on by Social Gospeller’s

fearmongering rants about the horrors of “extreme” socialism—put these aliens

into the cross hairs of a fierce AngloProtestant hatred.

Trotsky Fever Hits Largest Prison Camp in Canada

Trotsky Fever Hits Largest Prison Camp in Canada

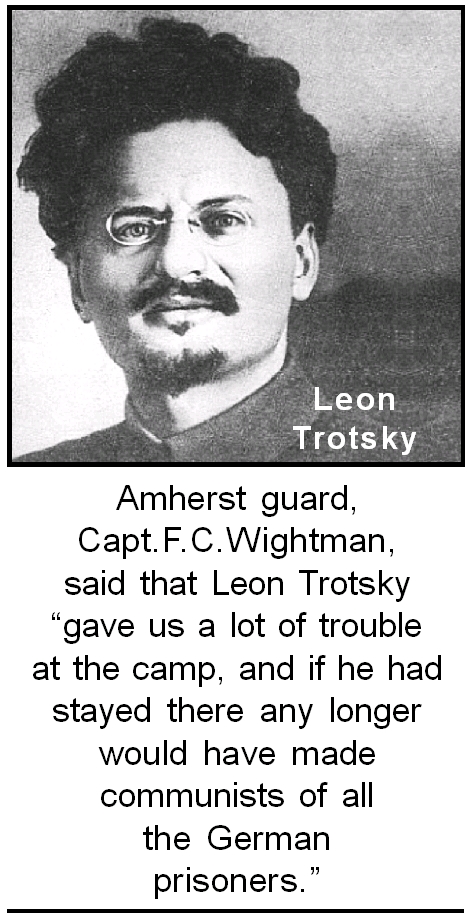

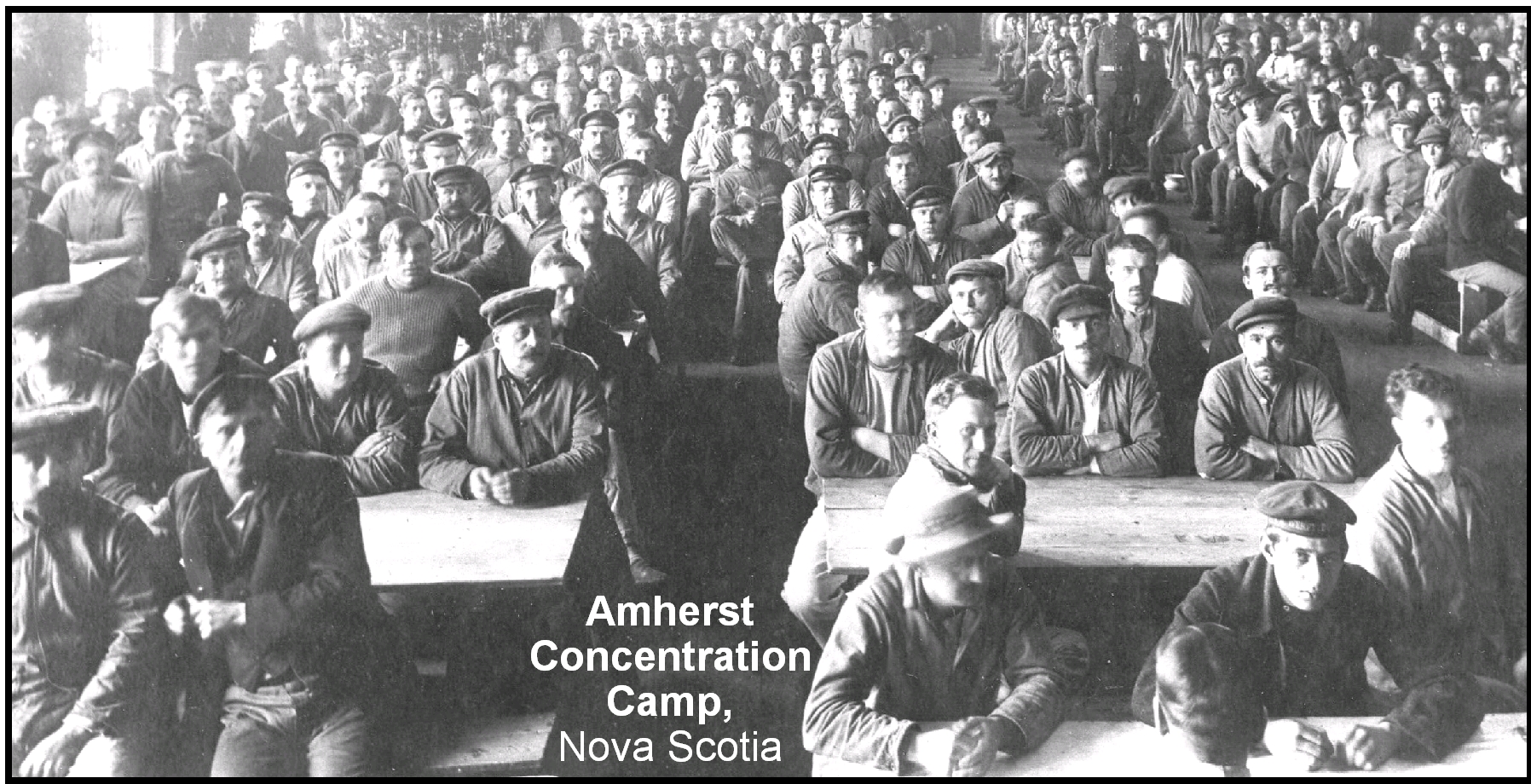

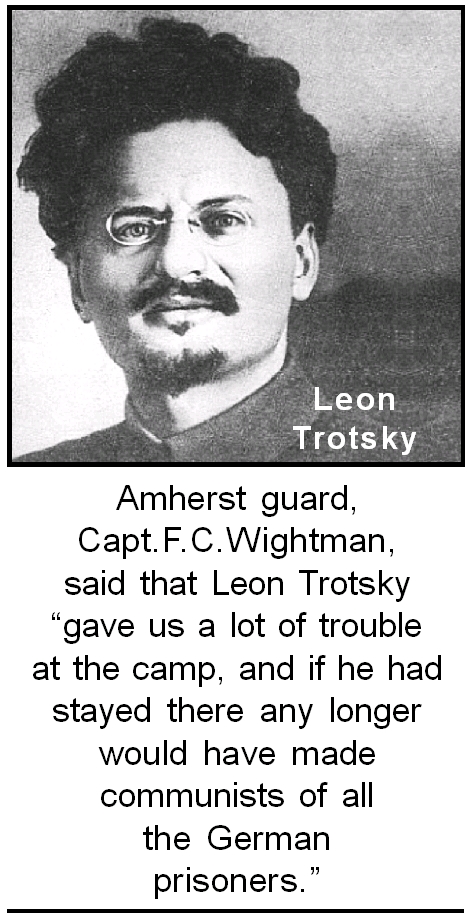

Leon Trotsky, the infamous Soviet revolutionary

of Jewish Ukrainian origins, was the best known prisoner ever held in a Canadian

concentration camp. His account of the physical, social and psychological

conditions inside Canada’s largest internment facility provides insights into

the potential for radicalisation among internees.

Trotsky, who later became the first leader of the

Red Army and a member of the Soviet Politburo (1919-1926), was born Lev

Davidovich Bronstein in the Ukraine. By the age of 21, in 1900, he was a devout

Marxist and had helped form a major union, spent two years in prison and had

been sentenced to four years in Siberia. Later, after his arrest for taking a

leading role in Russia’s failed 1905-1907 revolution, Trotsky was again forced

into exile. Besides his radical politics, Trotsky did not endear himself to

imperial elites with his outspoken self-identification as an “irreconcilable

atheist.”14

By 1917, Trotsky was rabblerousing in New York

City. When the February Revolution ousted the Czar, he and his family boarded a

steamer to return home to Russia. His narrative states that:

“At Halifax British naval authorities inspected the

steamer, and police officers made a perfunctory examination of the papers of the

American, Norwegian and Dutch passengers. They subjected the Russians, however,

to a downright cross examination, asking us about our convictions, [and] our

political plans….”15

After removing Trotsky, his wife and two

children, and others from the ship, he was separated from his family and taken

to the prison camp in Amherst, Nova Scotia.

Once there, he endured

“an examination the like of which I had never before

experienced, even in the Peter and Paul fortress. For in the Czar’s fortress

the police stripped me and searched me in privacy, whereas here our democratic

allies subjected us to this shameful humiliation before a dozen men.”16

Trotsky said Camp Commander Col. Arthur Morris

“made his career in the British colonies and in the Boer war.” Morris had led

imperial forces in Egypt, India, Burma, Ireland and the Gold Coast.17 Not

surprisingly, the two men did not exactly get along. “I did not show proper

respect when I spoke to him,” said Trotsky, “which made him growl behind my

back.”18

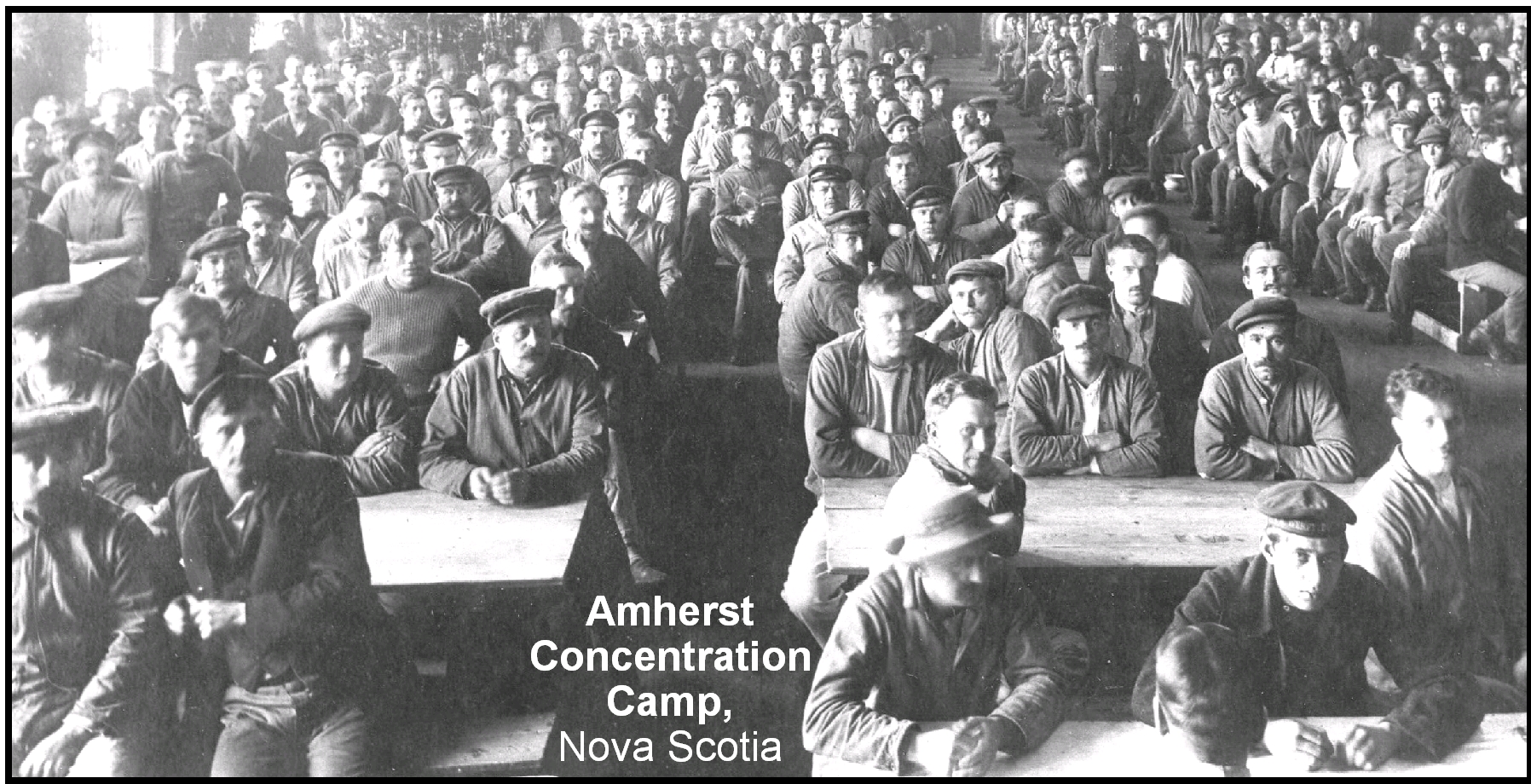

Trotsky described the “Amherst concentration camp” as

“an old...very dilapidated iron-foundry...confiscated from its German owner.”

Its prisoners, he said, were segregated into two distinct classes:

(1) 100 “officers and

civilian prisoners of the bourgeois class,” and

(2) 500 “sailors from

German boats sunk by the British” and 200 “workers caught by the war in Canada.”19

Trotsky’s relations with his fellow inmates

depended on their view of “revolutionary socialists.” While “officers and petty

officers, whose quarters were behind a wooden partition, immediately set us down

as enemies,” Trotsky said, the “rank-and-file...surrounded us with an ever

increasing friendliness.”20

To Trotsky, it was a chance to proselytise. “The

whole month...was like one continuous mass-meeting,” he said. “I told the

prisoners about the Russian revolution, about Liebknecht [a German socialist],

about Lenin,…and the intervention of the US in the [Russian civil] war.” With

“constant group discussions ....[o]ur friendship grew warmer every day.”21

When German officers complained about his sermonising,

Camp Commander Morris “locked Trotsky in the foundry’s old blast furnace as a

form of solitary confinement.”22

Trotsky’s narrative states that Morris “forbade me to make any more public speeches.

But…the sailors and workers,” he said, “responded to the colonel’s order by a

written protest bearing five hundred and thirty signatures.”23

Trotsky also reminisced that:

“prisoners gave us a most impressive send-off,….sailors

and workers lined the passage..., an improvised band played the revolutionary

march, and friendly hands were extended to us from every quarter. One of the

prisoners delivered a short speech acclaiming the Russian revolution and cursing

the German monarchy. Even now it makes me happy to remember that in the very

midst of the war, we were fraternizing with German sailors in Amherst.”24

The Amherst camp did not close until September

27, 1919, almost a year after WWI ended. Other Canadian prison camps kept

operating even longer, until February 1920. Authorities did not want to free

radicalised, leftwing prisoners of the class befriended by Trotsky, because they

feared that what Woodsworth called “extreme” socialism might spread like a

disease through Canada’s body politic.

14. Leon Trotsky, Testament, Feb. 27, 1940.

15. Leon Trotsky, My Life, 1930, p.217.

16. Ibid., p.218.

17. The Commandant

18. Trotsky, Op. cit., p.281.

19. Ibid., pp.281, 282.

20. Ibid., p.282.

21. Ibid., p.282.

22. Aaron Beswick, “Leon Trotsky forged notable month at Amherst foundry-turned

internment camp,” Herald, January 2, 2015.

http://thechronicleherald.ca/novascotia/1260632-leon-trotsky-forged-notable-month-at-amherst-foundry-turned-internment-camp

23. Trotsky, Op. cit., p.283

24. Ibid., p.285.

This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in In Strangers Within our Gates (1909),

J.S.Woodsworth revealed his contempt for east Europeans, Aboriginals, Asians and

Blacks. However, he had a slightly higher regard for Jewish immigrants, in large

part because he saw a better chance of assimilating them.

In Strangers Within our Gates (1909),

J.S.Woodsworth revealed his contempt for east Europeans, Aboriginals, Asians and

Blacks. However, he had a slightly higher regard for Jewish immigrants, in large

part because he saw a better chance of assimilating them.

After uttering a few niceties, Liberal Prime

Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier spoke out against the idea of even debating the

motion. Conservative Sir Robert Borden agreed, as did Liberal Quebec

nationalist, Henri Bourassa, who argued:

After uttering a few niceties, Liberal Prime

Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier spoke out against the idea of even debating the

motion. Conservative Sir Robert Borden agreed, as did Liberal Quebec

nationalist, Henri Bourassa, who argued: Trotsky Fever Hits Largest Prison Camp in Canada

Trotsky Fever Hits Largest Prison Camp in Canada