This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in

Captive Canada:

Renditions of the Peaceable Kingdom at War,

from Narratives of WWI and the Red Scare to the Mass Internment of Civilians

Issue #68 of

Press for Conversion (Spring 2016),

pp.5-14.

Press for Conversion! is the magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).

Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this

coupon,

or use the paypal link on our webpage.

If you quote from or

use this article, please cite the source above and encourage people to

subscribe. Thanks.

Here is the pdf version of this

article.

War Mania, Mass Hysteria and Moral Panic:

Rendered Captive by Barbed Wire and Maple

Leaves

By Richard Sanders,

Coordinator, Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT)

A century ago, in 1915, a youthful Canada was already waging its second

imperialist war overseas.1

The colony’s political and economic elites — ably represented in Parliament by

Sir Robert Borden and his pious AngloProtestant cabinet — had rallied mainstream

Canada behind the imperial hubris of a phoney “war to end all wars.”

Subjected to every propaganda trick

imaginable—from patriotic political speeches, popular novels, classroom tripe

and religious sermons, to flag-waving parades and church picnics—Canadians were

propelled into a mass hysteria that justified not only the imperial war abroad

but harsh repression on the homefront.

Exploiting the endemic classism, racism and

xenophobia that riddled mainstream Canadian society, opinion leaders demonised

their foreign enemies, and rationalised the domestic persecution of a very

specific demographic of newcomers. Armed with the wartime pretext that Canada

was under siege by diabolical aliens who had infiltrated the gates of our

“Peaceable Kingdom,” the Conservative government crafted draconian new security

legislation. Passed in 1914—with the loyal support of all Liberal MPs, and

the lone Labour Party politician in Parliament—the War Measures Act gave

authorities a new arsenal of repressive powers for exerting control over

Canadian society. Among these powers were tools to monitor and detain anyone

even suspected of becoming a potential enemy of the state.

History has been repeating itself ever since.

When Harper’s Conservative government used Bill C-51 to revamp Canada’s

institutions of repression, the so-called Anti-Terrorism law was approved with

overwhelming Liberal Party support. Armed with these new weapons, Canada’s

secret police and spy agencies can now target and pre-emptively jail anyone they

believe might possibly threaten the established order of business.

The legal boundaries of the word “terrorist”

have been redrawn. Expanded to capture activists said to cause “interference

with the economic or financial stability of Canada,” the term “terrorism” now

encloses those “unduly influencing a government” by “unlawful means.”2 This

makes terrorists out of unionists who use illegal strikes, or even pacifists

devoted to using Gandhian acts of nonviolence.

After 100 years, Canadian business elites,

driven by the same endless pursuit of profits, still wrap themselves in the

Maple Leaf and use simple narratives to instil a fear of fiendish, foreign

enemies. And, Canada’s security-fixated, state institutions are still the

gravest threat to our civil rights.

While the foreign enemies du jour are now

said to be radicalised Muslims, Canadians of a century ago were caught in an

epidemic of fear that was stirred up by dire warnings that east Europeans—mostly

Ukrainians—were being radicalised by militantly socialist labour activists.

Between 1914 and 1920, Canada was held captive

not just by jingoism, but by a virtual dictatorship. When MPs unanimously

passed the War Measures Act, they gave extraordinary powers to Borden’s clutch

of Tories. His Cabinet—working with the Governor General, a son of Queen

Victoria—used the “emergency” of war to bypass Parliament and issue laws they

saw as “necessary...for the security, defence, peace, order and welfare of

Canada.”3

By dictating the legal definitions captured by

these vague grab-all terms, the Governor in Council also became Canada’s

semantic gatekeeper. But besides being the despotic guardian and ward of the

word of law, this official cabal helped harness prevailing national

narratives to capture the hearts, minds and loyalties of mainstream society.

This public support was required not only to wage the imperial war abroad, but

the one at home as well.

The War Measures Act of 1914 was a reaction to

what its framers called “the existence of real or apprehended war, invasion or

insurrection.”4 Gripped by

fear of revolts, rebellions and resistance to authority, global elites were in

crisis. Canada was not immune to the political anxiety disorder that plagued

imperialists around the world. Canadian elites were preoccupied and obsessed

with phobic worries about seditious uprisings by radicalised socialists and

labour activists. By 1917, the angst among Conservative/Liberal elites went

viral. Canada was under siege by mass, public hysteria. This moral panic attack

is known as the “First Red Scare.”

But the foreboding that afflicted European

capitalists began decades before the Russian revolutions of 1917. Their fear

was sparked by popular mutinies that upset imperial and monarchic control on

five continents. Popular insurrections and revolutions included: Ghana, 1900;

Angola, 1902; Bulgaria, Macedonia, Greece, 1903-1908; Armenia, 1904; Namibia,

1904; Paraguay, 1904; Argentina, 1905; German East Africa, 1905-1906; Russia,

Poland, Finland, Ukraine, Latvia, Estonia, 1905-1907; Persia, 1905-1909;

Romania, 1907; Turkey, 1908; Bali, 1908; Syria, 1909; Morocco, 1909-1910;

Monaco, 1910; Portugal, 1910; Mexico, 1910-1920; China, 1911-1913; Mongolia,

1911-1921; Balkans, 1912-1913; Ireland, 1912-1923; Albania, 1912-1914; and South

Africa, 1914.

So, for decades prior to WWI, Europe’s

colonial powers were increasingly terrified by growing social movements for

democracy, justice and labour rights that were organising mass protests and huge

general strikes. The nearly successful Russian revolution of 1905-1907, pushed

many capitalist power brokers to conclude that they needed to take even more

desperate measures to contain the spread of socialism, if not to crush it

completely.

During WWI, Canadian authorities rallied loyal

citizens around the Union Jack to support Britain’s imperial interests abroad.

But the War Measures Act not only consolidated state power to wage a foreign

war, it provided special tools to quell a feared socialist revolt within

Canada’s borders. The war thus furnished a convenient pretext for targeting

domestic enemies of the state. Authorities imagined that foreign radicals who

had infiltrated Canada’s gated community, were an infection that had to be

stopped from spreading throughout the body politic. Cabinet used its new powers

of preventative, mass detention to capture and enslave thousands of single,

recently-laid off labourers mostly from eastern Europe. These young men—then

amassing in Canada’s cities—were feared not only as a source of anticapitalist

ideas, but as the group at highest risk of being agitated into action by radical

socialists.

Capturing History

The WWI-era repression of

Canada’s radical left has been all but erased from mainstream narratives about

the period. Instead, the war’s centenary has created an onslaught of

spellbinding stories that pull at our collective heart strings and build

nationalist feelings that support the armed forces. The government, corporate

media and mainstream civil-society groups have memorialised Canada with poignant

tales of soldiers who lost their lives in WWI.

Official WWI narratives have also been used to

justify Canada’s military and foreign policies. “Nothing has changed,” said

then-Prime Minister Harper at a 2014 ceremony marking WWI. Continuing with what

the Canadian Press called a “veiled reference to Canada’s tough stands in

support of Ukraine and Israel,” he went on to say that “Canada is still loyal to

our friends, unyielding to our foes,” and stands “once again beside allies whose

sovereignty, whose territorial integrity—indeed, whose very freedoms and

existence—are still at risk.”5

(Canada’s “tough” support for the Ukrainian and Israeli governments

continues apace under the Trudeau Liberals.)

The October 22, 2014, murder of an army

reservist at Ottawa’s National War Memorial (built to commemorate our WWI

military losses), was used to justify the deployment of troops and warplanes to

Iraq. On the next day, Harper told Parliament that “laws and police

powers...in the area of surveillance, detention, and arrest ...need to be much

strengthened.”6 On October

24, then-Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney said the government was

“eyeing the thresholds established in Canadian law for

the preventive arrests of people thought to be contemplating

attacks that may be linked to terrorism.”7 (Emphasis

added.)

The pre-emptive jailing of

those thought to be thinking about actions that might be “linked

to terrorism,” requires extreme paranoia. Ironically, Canada’s current war

against IS—framed as a humanitarian attack on ultraconservative religious

fanatics—was begun by evangelical neocons keen on restraining domestic civil

liberties.

Missing from the militarised human-interest

stories of WWI are historical narratives about Canada’s harsh attacks on

domestic civil rights. In 1914, when Tories and Liberals passed the War

Measures Act, Cabinet was given unlimited powers to restrict and control

communications, travel, manufacturing, property and trade. The Act also gave

them absolute powers to arrest, detain and deport anyone, without trial.

Cabinet was soon using this power to wage war against a specific set of

immigrants. Many of them—not coincidentally—were sympathetic to anticapitalist

ideas and radical, labour actions.

While official stories of Canada’s WWI

internment now critique the ethnic profiling of Ukrainians, they usually ignore

the role of economics, class and politics in targeting them. Such renditions of

history are common among Canada’s nationalist Ukrainians. For example, on

Remembrance Day 2010, the ultraright Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC) said

that:

“Thousands of Ukrainian Canadians were jailed in

Canadian internment camps....not because of anything they had done, but only

because of where they had come from.”8

Concentration Camps

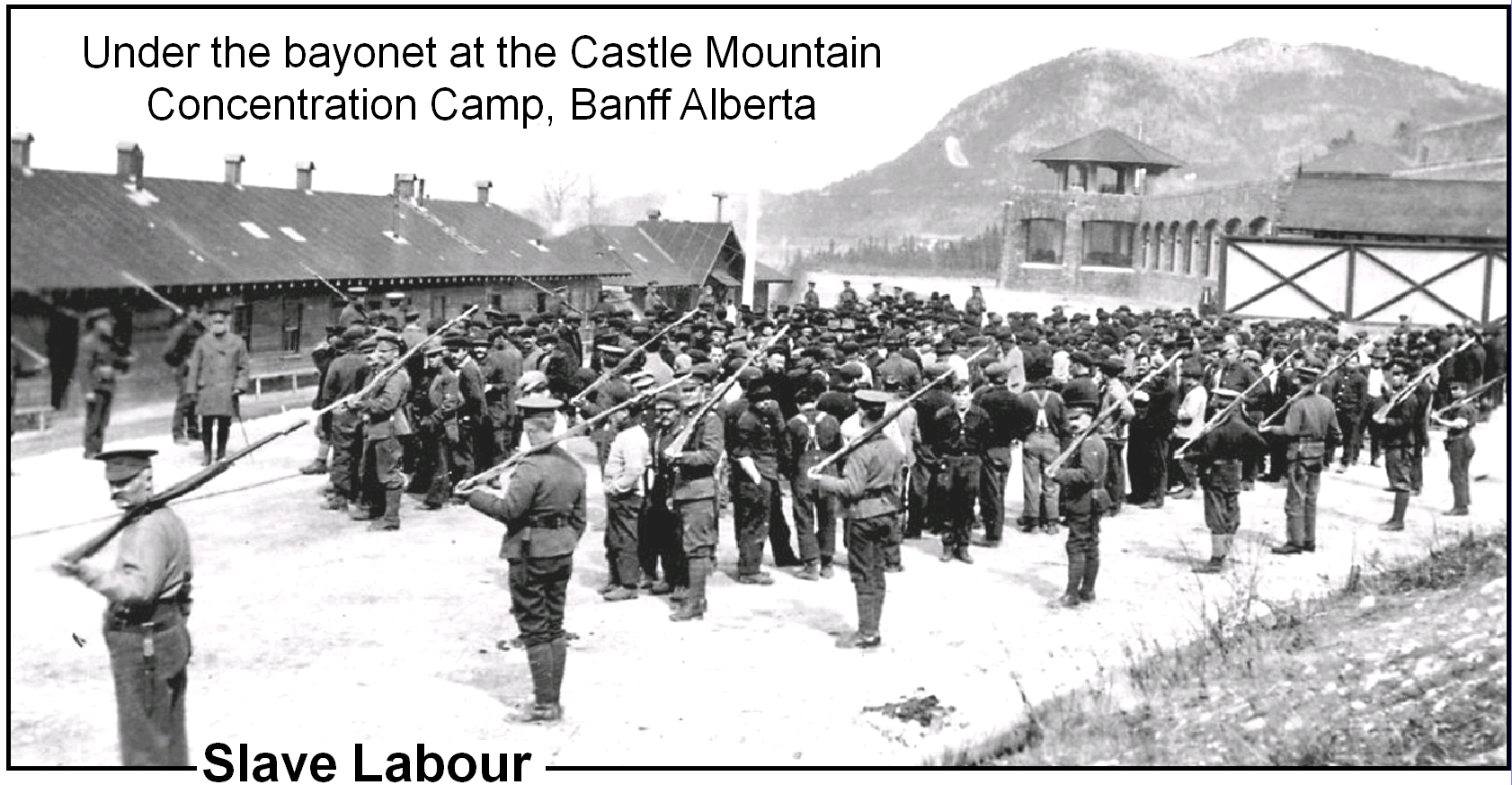

Between 1914 and 1920, 8,579 men “of enemy

nationality” were interned in what authorities originally called “Concentration

Camps.” Of these, 7,762 (90%) were civilian residents of Canada. Also imprisoned

were 81 women and 156 children. While 2,009 of the men were German, 5,954 were

listed as “Austro-Hungarians, covering Croats, Ruthenians, Slovaks and Chzecks.”9

(Serbs were also among those interned.) About 5,000 of these

“Austro-Hungarians” were actually Ukrainian.

Canada’s 24 internment

facilities were commanded by Maj.Gen. Sir William Otter, who is still fondly

heralded as the “father” of

Canada’s

Army. His official report, Internment Operations, 1914-1920, says he

“suspected that the tendency of municipalities to ‘unload’ their indigent was

the cause of the confinement of not a few.”10 By

mid-1915, 4,000 of the aliens forced into these prison camps, were being

described as “indigent.”11

To abide by the Hague Convention on POWs, Otter

had two classes of internees. Only a few were among what he called the military

“officer class or its [civilian] equivalent.” Mostly German, these “first class”

prisoners—held largely in cities—received “better quartering and subsistence.”12 And,

they were not forced to work. “Second class” internees were mostly Ukrainian

civilians. Banished to rural camps, they laboured under the gun, endured hunger,

disease, unsanitary conditions, overcrowding and dangerous work environments.

Some were beaten, prodded with bayonets, or viciously tortured. Ten were shot

dead trying to flee the camps.

Otter’s narrative claimed that

“very little friction occurred between troops and prisoners.” His report also

said he had “little complaint” about guards. Otter did admit that

Canada’s prison camp conditions may have led to “insanity.” Noting that

“Insanity was by no means uncommon among the prisoners,” Otter said that in some

cases, “the disease possibly developed from a nervous condition brought about by

the confinement and restrictions entailed.” In “many other cases,” Otter said

he “suspected” that the “insane” were “interned ...to relieve municipalities of

their care.”13

The psychotic brutality of Canadian camp guards

was described by US Consul Samuel Reat. He said in 1915 that some prisoners in

the Lethbridge Alberta camp were put

in “dark cells and given a diet of bread and water from 1 to 4 days.” Others, he

reported, were “handcuffed and drawn up so that their toes just touch the

floor.” Another US Consul, G.Willrich, said “petty officers” inflicted

punishments to “gratify their brutal instincts,” “as is so often the case when

men of inferior intelligence are invested with autocratic powers.”14

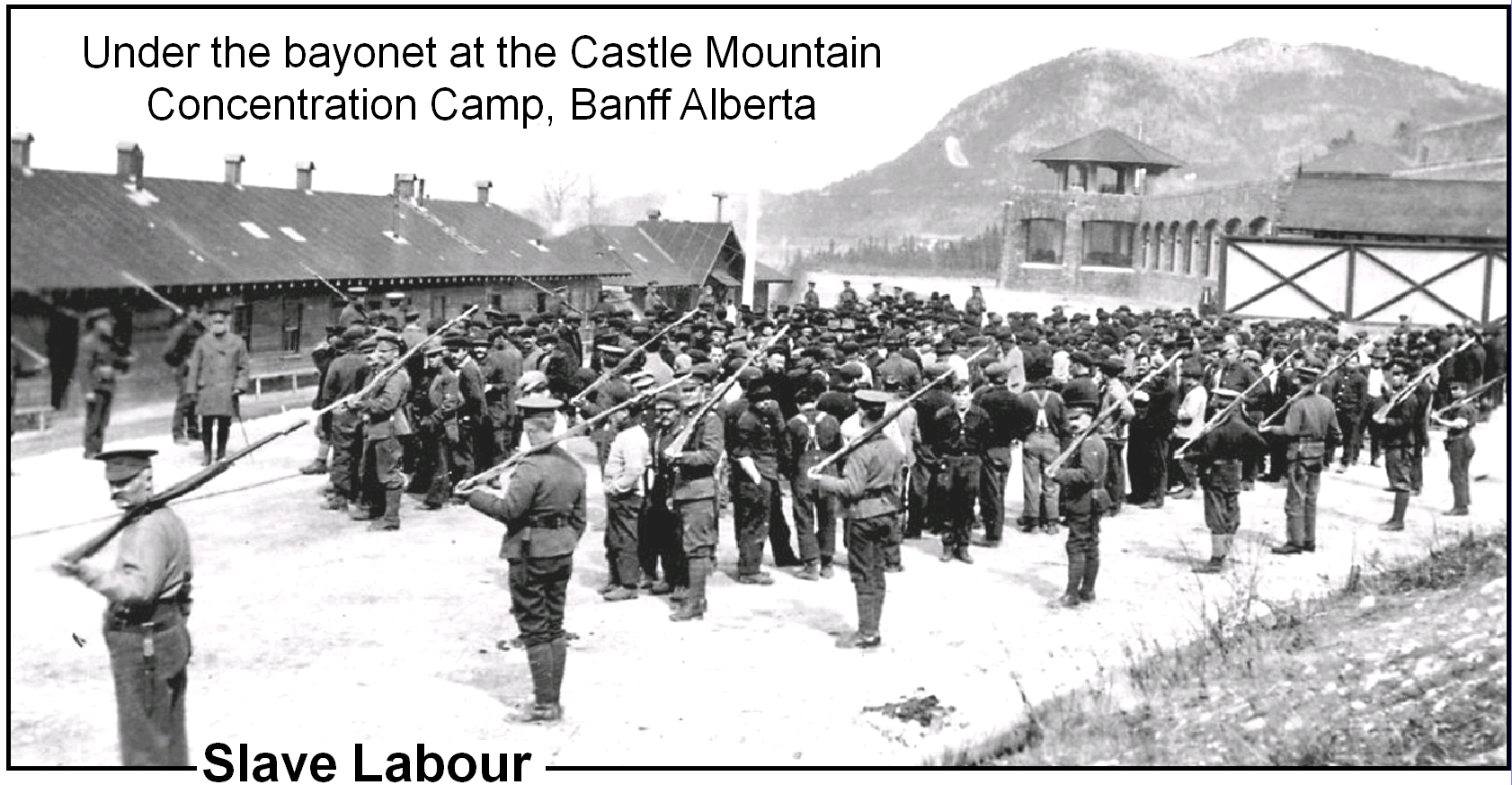

Slave Labour

Although “first class” internees,

mostly German officers, were not forced to work, “second class” prisoners,

mostly Ukrainian civilians, were used as slaves. Even upon release, their

slavery did not end. In 1916 and 1917, when the British Empire’s increased

demands for Canadian cannon fodder in Europe led to a shortage of workers, the government’s corporate friends asked

for welfare assistance. Borden’s government was only too happy to oblige by

providing thousands of foreign slaves from

Canada’s labour camps. In the official narratives however, these historic

realities were rendered in more euphemistic terms. Otter’s narrative captures

the official history with these words:

“[W]hen the most strenuous call for reinforcements was

made by the Allies, the depletion of men in many of the large corporations of

the country was so keenly felt that application [was] made for the services of

our prisoners to supply the want.... This system proved a great advantage to the

organizations short of labour.”15

Otter also reported that 6,000

“Austrians,” mainly Ukrainians, were “released from confinement on signing a

‘parole.’” For example, over 1,300 mostly Slavic inmates were released from a

northern Ontario camp in Kapuskasing when it was “decided to parole them to

work for the Dominion Steel Corporation and other big manufacturers.”16

Paroled prisoners were kept on a tight leash. They could be returned to

captivity if they failed to report regularly to the police, or lost their jobs.

Col.Anderson-Whyte, a former guard from the

Castle Mountain internment camp

in Banff, was more blunt: “We had plenty of labour. Anybody who asked us to do

anything, we provided the slaves.”17 Enslaved

by federal and provincial governments and private firms, they hewed trees, built

structures, fences, railways, roads and parks, and sweated on farms or in

factories, steel mills and coal mines.

Getting a pittance for their 10-hour work days,

many got only 25 cents a day for hard labour, when a standard wage was 20 cents

an hour. Although not paid until after the war, some were not paid even then. By

mid-1929, the government still owed $23,000 to prisoners for their work,18 i.e.,

92,000 hours of labour. In

contrast, on top of his pension, for his part in running Canada’s slave labour

camps, Otter got $30,000, i.e., $5,000 per year from 1914 to 1920. (In 1914,

$5,000 was the equivalent of $103,000 in 2015.)

Some internment-camp labourers were denied any

allowance. As the Consul of Switzerland wrote in 1917, after visiting the camp

near Fernie, BC:

“They complain that the allowance of One dollar per

month has been withdrawn in consequence of which some of the men are absolutely

destitute.”19 ($1 in 1914

was equal to $21 in 2015.)

Mark Workman, president of the Dominion Iron and

Steel Corp., was so enthused with the government’s forced labour program that he

requested “troublesome” internees. As he put it, “there is no better way of

handling aliens than to keep them employed in productive labour.” In 1917,

Workman asked Borden to request that Britain transfer their internees to Canada

for work in his Cape Breton mines.20

Even after November 11, 1918, with WWI over,

Canada continued its repressive internment program. The government reported

that as of December 19, 1918, there were still 2,222 prisoners being held in

four camps: Munson, AB (63), Vernon, BC (388), Kapuskasing, ON (1,007) and

Amherst, NS (764).21

Conflicting Narratives

To explain why some Canadian prison camps stayed

in operation until 1920, BC lawyer Diana Breti argued that the

“forced labour program was such a benefit to Canadian

corporations that internment was continued for two years after the end of the

War.”22

In 2005, Liberal MP Borys

Wrze-snewskyj gave Parliament the same narrative when he lauded efforts by the

Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC). He said:

“This infrastructure development program benefited

Canadian corporations to such a degree that even after the end of World War I,

for two more years the Canadian government carried on the internment.”23

This official story is still

found on the UCC website. “This infrastructure development program,” says the

UCC, “was so beneficial to Canadian corporations that the internment program

lasted for two years after the end of the war.”24

The UCC has worked closely with government ever

since Prime Minister King’s Liberals facilitating its creation in 1940. Their

shared goal was to unify Ukrainian anticommunists and to marginalise their

common socialist enemies. (See “Consolidating the Ukrainian Right,” p.46)

While it is useful to

expose the confluence of government and corporate interests in exploiting

WWI-era slave labour camps, this narrative ignores the political function of

internment. Camps were also used to contain the spread of radical socialism.

This was particularly obvious after the Russian revolution of 1917.

In 1917, Canadian censors

banned many leftwing publications, making hundreds of books and periodicals

illegal to print, import, distribute or even possess. By September 1918,

Borden’s regime outlawed all publications in languages spoken within enemy

states, including German, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Turkish, Romanian, Ukrainian,

Russian, Finnish, Syrian, SerboCroatian and Latvian. This ethnic profiling did

not apply to religious texts or other materials that officials found

unobjectionable.25 Describing

this crackdown, labour activist Michael Martin wrote that although

“[t]he pretext was the war; the real goal was to limit

and control the effects of the Russian Revolution. At the same time, fourteen

political organisations were banned, as were publications of trade unions and

socialist and anarchist organisations. On

October 11, 1918, exactly one

month before the armistice, the government prohibited all strikes, and made

conciliation obligatory and binding in industrial disputes. [A] pattern of

action was installed which was ...putatively aimed at wartime security, but

actually aimed at controlling and disciplining the working class.”26

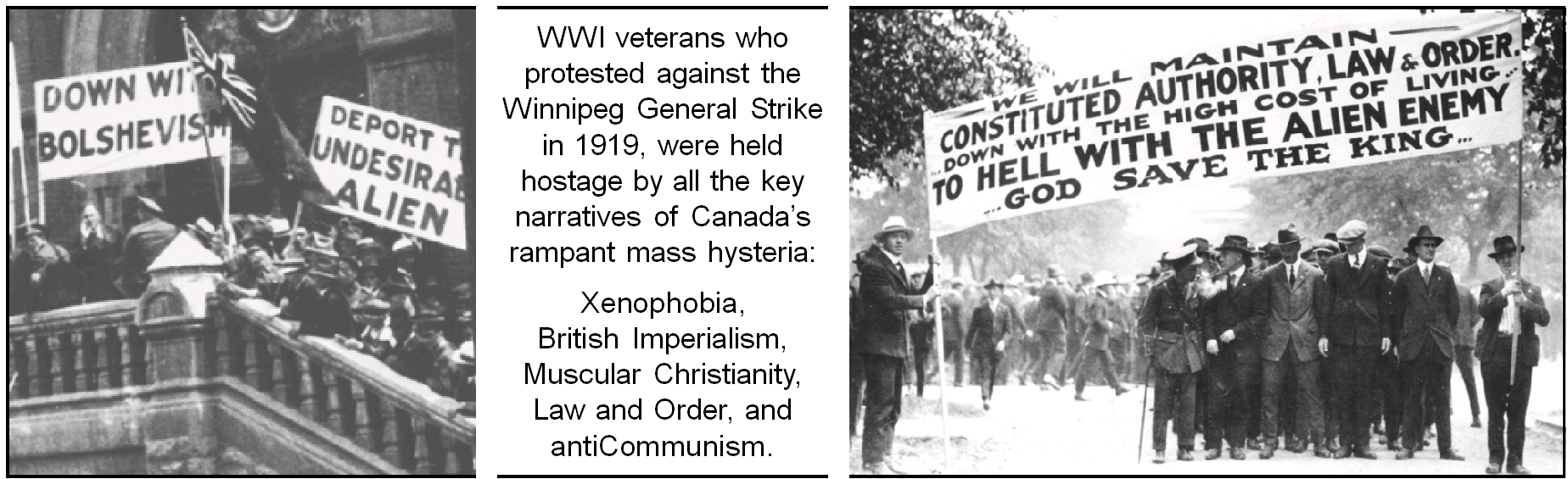

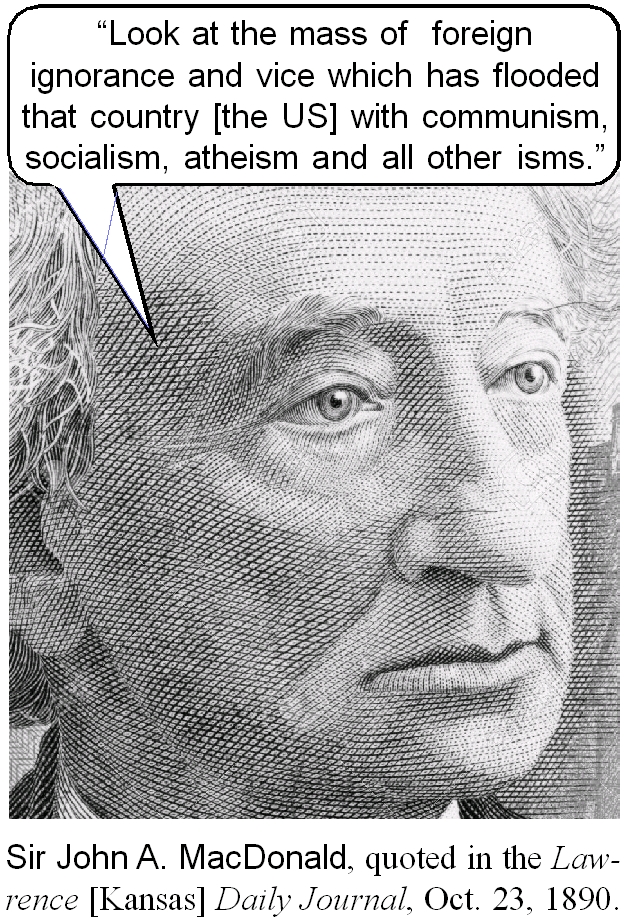

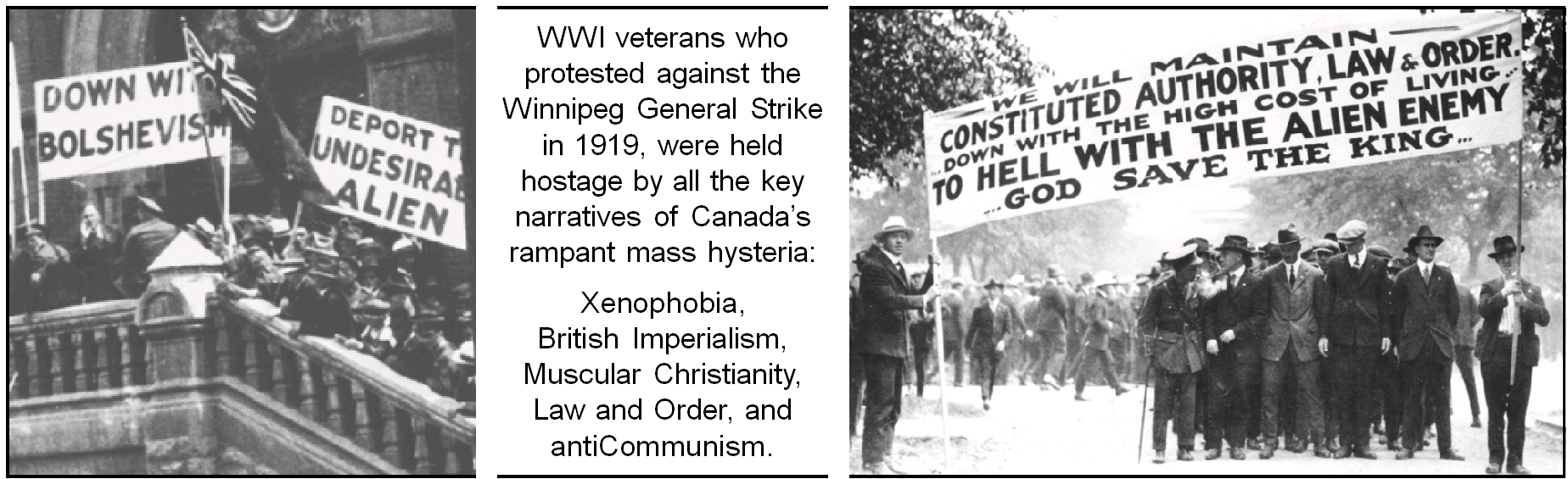

Canada’s

antiRed psychosis reached a frenzied peak in the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike.

The madness was inflamed by elites at every level, from the federal Cabinet to a

local “Citizens’ Committee” of

Winnipeg’s

richest industrialists, lawyers, bankers and politicians. Joining the fray were

media moguls whose papers branded radical labour activists with slurs like

“Bolsheviks,” “Bohunks” and “alien scum,” or depicted them in cartoons as

crazed, bomb-throwing anarchists.

Despite such vivid propaganda

tactics, when police rounded up strike leaders at gunpoint in late-night raids,

30,000 supporters rallied on June 21, braving the city’s ban on all public

gatherings. When Mounties got orders to fire into the crowd, they killed two

people. They then charged in on horseback, injuring dozens. Fleeing protesters

were beaten with bats and wagon spokes wielded by “special police” and about 100

“Reds” were arrested.27

In summing up this “Bloody Saturday” police

riot, Sir George Foster, MP, remarked that: “Some blood was shed but law and

order was maintained….”28

Winnipeg was an occupied city patrolled by army

trucks mounted with machine guns.29 When

the strike was called off, radical labour activists were fired or black listed

and the media continued to promote antiRed narratives. The madness soon spread

as Mounties “from Victoria to Montreal raided the homes and offices of socialist

and labour leaders.”30 That

summer, about 200 radicals were rounded up. “Many of those arrested,” reports

historian Don Avery, “were moved to the internment camp at Kapuskasing, Ontario,

and subsequently deported in secret.”31

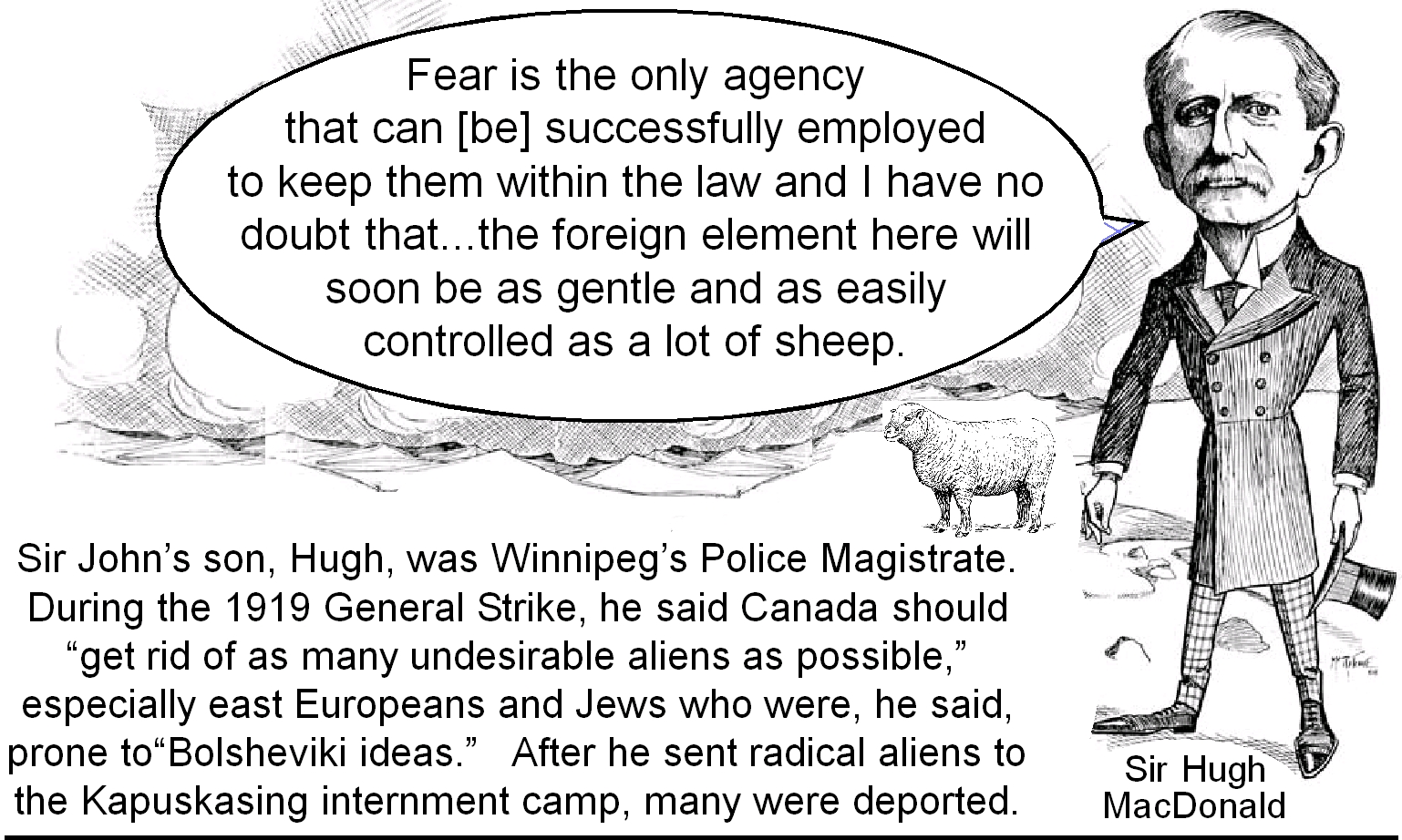

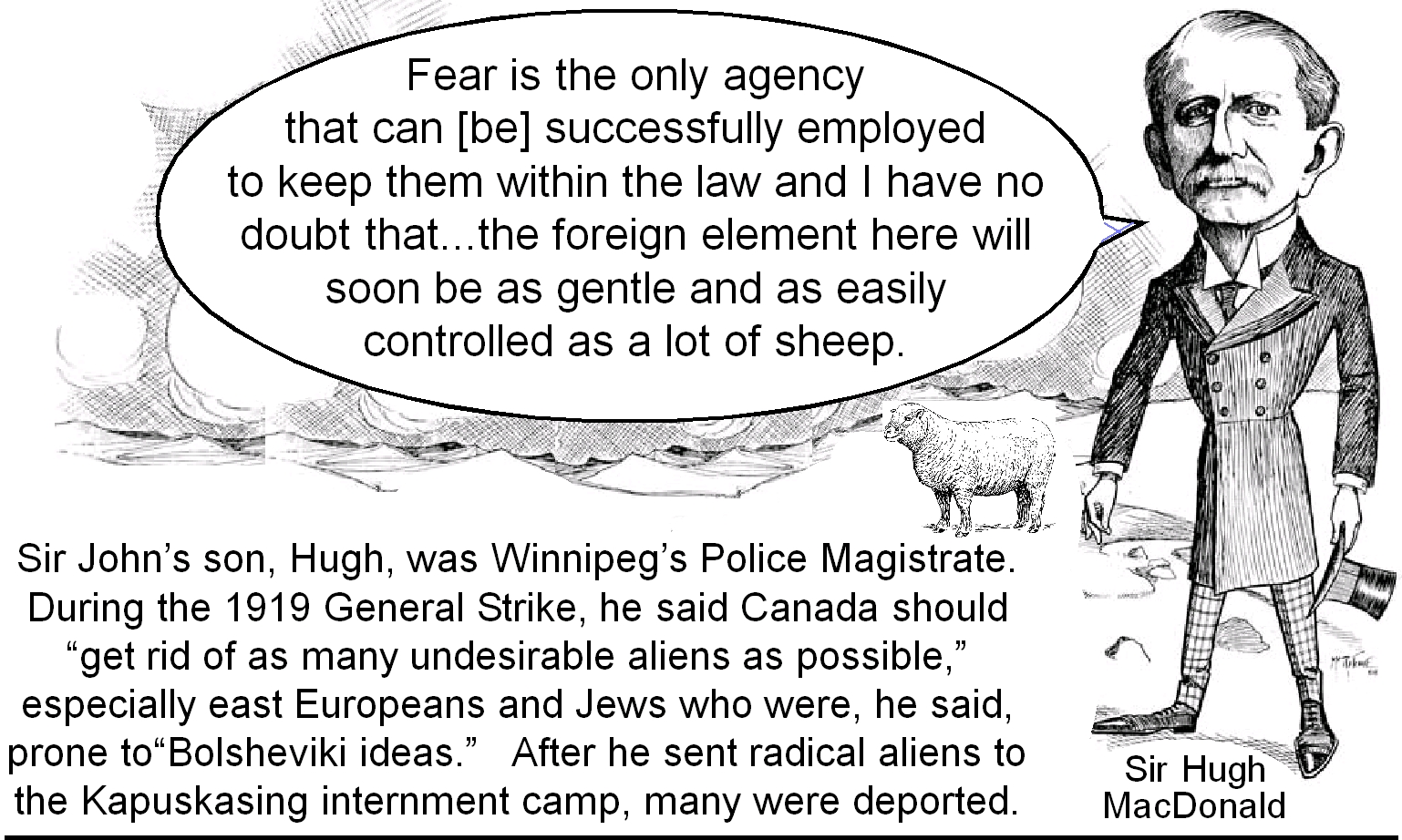

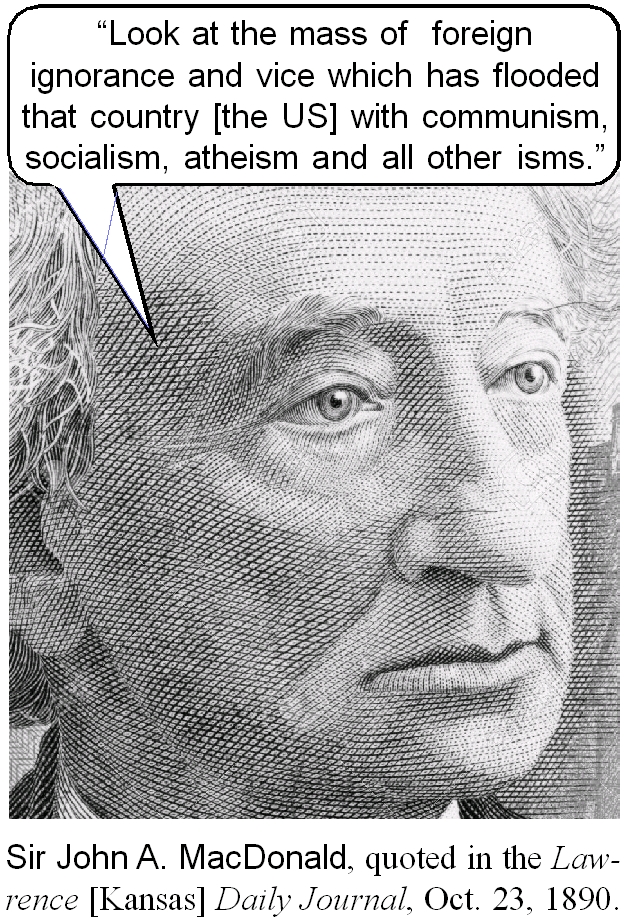

This treatment was pushed by Sir Hugh MacDonald,32 Winnipeg’s

Police Magistrate and the son of Sir John A. MacDonald. In 1919, Sir Hugh wrote

to Canada’s Interior Minister Arthur Meighen about “getting rid of as many

undesirable aliens as possible” because of the “large extent Bolsheviki ideas

are held” by Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, and especially Jews. He urged Meighen

to “make an example” of these radicals, by saying that

“fear is the only agency that can [be] successfully

employed to keep them within the law and I have no doubt that if the Dominion

Government persists in the course that [it] is now adopting the foreign element

here will soon be as gentle and as easily controlled as a lot of sheep.”33

“fear is the only agency that can [be] successfully

employed to keep them within the law and I have no doubt that if the Dominion

Government persists in the course that [it] is now adopting the foreign element

here will soon be as gentle and as easily controlled as a lot of sheep.”33

To see why Canadian prison camps kept operating until 1920, we must look at the

global context. While Russia’s revolution inspired many poor workers around the

world, it alarmed elites in Canada, the US, Europe and elsewhere. Panic

stricken by Russian events, and fearful of home-grown radicals, desperate

powerbrokers scared their societies into a mass psychosis of antiRed hysteria.

The paranoia of this “First Red Scare” was fired up by state propagandists,

media owners, church leaders, and progressive civil-society activists held

captive by xenophobic narratives.

The Canadian government’s madness to contain the

Red Menace at home was paralleled by a mounting frenzy to collar if not wipe out

communism abroad. Following WWI, Canada joined the US, Britain, France, Greece,

Italy, Japan and others, in a military invasion of Soviet Russia to turn back

their revolution.

In March 1919, France’s PM Georges Clemenceau

launched the Cold War’s “Containment Policy.” He called for an international

cordon sanitaire to encircle and quarantine Bolshevism, as if it were a

communicable disease. Britain’s War Secretary, Winston Churchill, shared this

vicious pathology. His rhetoric used a graphic metaphor to demand the deadly

encirclement of an infant’s neck. Using the murderously psychopathic trope of

throttling a newborn, Churchill said Bolshevism was a baby that “must be

strangled in its cradle.”

So it was that in 1919 more than 150,000

troops—including 4,200 Canadians—invaded the newborn Soviet state. “Canadian

troops joined soldiers from thirteen countries,” said historian Benjamin Isitt,

“in a multi-front strategy of encirclement designed to isolate and defeat the

Bolshevik regime.”34

Despite this, the prevailing

view is that political profiling was not used to target aliens for internment.

Even progressive political scientist Reg Whitaker said in 1986 that in WWI “many

Ukrainians had been interned in Canada, but not, it would seem, with any

political or ideological selectivity.”35

4Rs:

Recession, Radicalism, Rebellion and Repression

Between 1910 and 1914 alone,

about 70,000 Ukrainians—mostly single men —migrated to Canada. Most were

exploited in low-salary jobs building railways and roads, or working in mines,

mills or foundries. Because they dominated some of the hardest-hit job sectors,

Ukrainians were disproportionately affected by the major recession that hit

Canada between 1913 and 1915. For example, of the 54,000 railway workers who

lost their jobs in that recession,36 a

large percent were Ukrainian.

After the Liberal government

imposed its severe “head-tax” on Asian immigrants in 1907, Chinese railway

“coolies” were replaced largely by Italians and Ukrainians. Most immigrant men

entering Canada in the decade before WWI were forced into brute manual labour.

Many endured oppressive and dangerous conditions in remote, company-run work

camps. During the early decades of the 20th century, these bunkhouse camps were

home and workplace to hundreds of thousands of immigrant men. These poorly-paid

loggers, miners and railway workers did much of Canada’s most backbreaking work.

Railway workers were among the

worst off. Official records conservatively show that between 1901 and 1918,

12,816 “navvies” were killed in job-related accidents, while 99,668 were

injured. “A great many of

these,” said University of Manitoba historian Orest Martynowych, “were Ukrainian

immigrants.” He went on to

say that in 1912,

“a foreign consul familiar with conditions in

Europe and South American

stated that he knew of ‘no other country where the rights of workmen have been

so flagrantly abused as on railway construction in Canada.’”37

Even convicts doing railway

work had better housing, and shorter hours, than Canada’s alien “navvies,” said

an observer who likened their conditions to “lesser forms of serfdom” and

“peonage.”38

Despite being the backbone of

Canada’s economy, mainstream unions turned a blind eye to the workers in these

camps. Two main factors affected large unions’ disinterest in organising them,

said Erica Martin, “the racism which beset early Canadian labour activism” and

“the fact that most manual workers on the frontier were immigrants.” Only in the

early 1920s did big unions begin to take an interest in Canada’s work camps

because they “felt threatened by ‘radical’ groups like the International Workers

of the World (IWW) which were attempting to organize camp men.”39

By 1911, the anarcho-socialist

IWW had about 10,000 Canadian members, mainly in mining, logging and railway

construction camps. They gained strength by uniting thousands in strikes and

walkouts to achieve better wages and safer work conditions in the camps.

By the summer of 1913, thousands of Ukrainians,

many laid off from death-defying railway work where they were radicalised by the

IWW, moved into western Canadian cities. The police used vagrancy laws to

arrest them for loitering, and some were deported.40

Speaking

of indigent labourers in western Canada at that time, Ukrainian Canadian

academics, Bohdan Kordan and Peter Melnycky, wrote that:

Speaking

of indigent labourers in western Canada at that time, Ukrainian Canadian

academics, Bohdan Kordan and Peter Melnycky, wrote that:

“these people...were interned when urban municipal

councils, concerned about this additional burden on the tax rolls and unwilling

or unable to provide relief for them, insisted they were ‘a threat to civil

order.’ The policy of internment offered local authorities the means with

which to deal with the thousands of destitute who were milling about the

streets of urban centres.”41

(Emphasis added.)

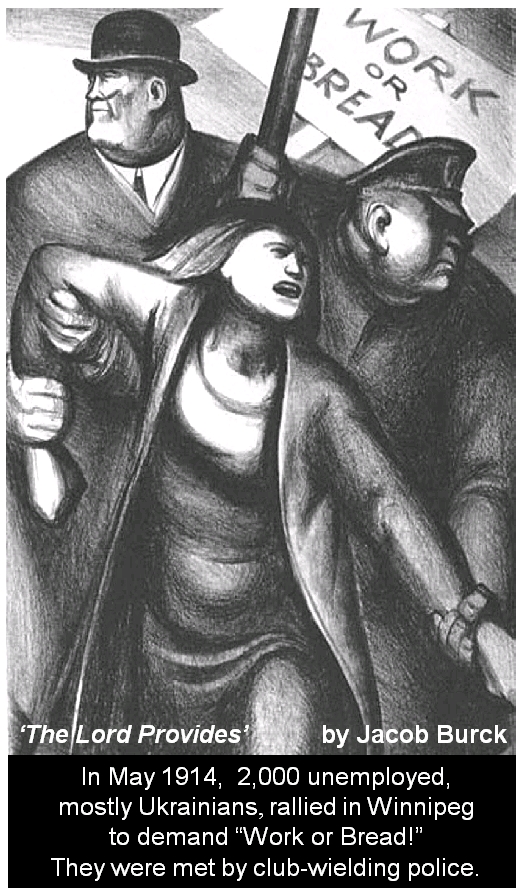

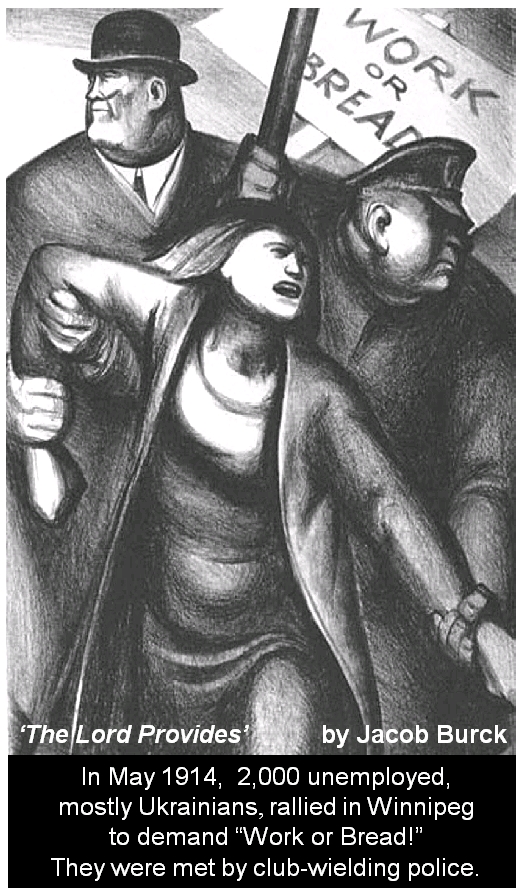

But radicalised Ukrainians were

not merely “milling about the streets,” they were protesting in the streets.

In May 1914, 2,000 unemployed, mostly Ukrainians, rallied in Winnipeg. Carrying

shovels, they called for “work or bread!” When police tried to arrest one of

their speakers, an officer was beaten. The crowd was driven back by 20

club-wielding constables.

Business leaders supported

Canada’s roundup of indigent aliens. In August 1914, CPR president Sir Thomas

Shaughnessy urged friends in government to create detention camps for laid-off

Germans and “Austrians.”42

Later that month, the War Measures Act was passed and internment stations opened

in Montreal and Kingston. Six prison camps opened that September, with five in

western Canada.43

To solve the growing crisis, Borden’s government

considered conscripting foreigners into the military. Another idea was to

encourage unemployed aliens to leave Canada for the US. When Borden cabled

Canada’s colonial masters in Britain for advice, he noted that the

“[s]ituation with regard to Germans and Austrians,

particularly Austrians [is] very difficult. From fifty to one hundred

thousand will be out of employment during coming winter as employers are

dismissing them everywhere under compulsion of public opinion.”44 (Emphasis

added.)

It was essential, Borden said, to either “let

them go, provide them with work or feed them, otherwise they will become

desperate and resort to crime.” The “crime” that scared Canadian elites was not

loitering, it was insurrection. The colonial office in London suggested that

Canada enslave these troublesome, unemployed aliens. Imperial authorities

couched this in euphemisms saying that if Canada provided enemy aliens with food

and shelter, “it would be quite proper under war conditions to make them labour

at public works.”45

Even after the War Measures

Act was enacted and internment had begun, protests by unemployed foreigners

continued to grow. In April 1915, 5,000 “unemployed non-unionized ‘foreigners’”

hit Winnipeg’s streets demanding “bread and work.” Police met them with clubs.

Another Winnipeg protest of 15,000, took place three days later. In mid-May,

hundreds of aliens, many Ukrainian, left Winnipeg. In search of work, they

walked to the US

border. Once there, 200 were arrested and sent to internment camps.46

The government and its friends

in business, shared a growing fear that radical immigrants, ravished by poverty

and with nothing to lose, posed a threat to what the War Measures Act called the

“peace, order and welfare of Canada.” Destitute east Europeans, roused by hunger

and socialist ideals, were menacing. With the economic crisis at home and war

abroad, authorities had a convenient excuse to round up and thus contain those

unemployed aliens who were seen as radicals prone to disruptive street protests

and labour unrest.

Meanwhile, the official story

was that indigent aliens were interned for their own good. In 1918,

then-Minister of Justice, Charles Doherty, an army veteran of the 1885 Northwest

Rebellion, told Parliament that poor aliens were interned out of Anglo-Canadian

kind-heartedness. Because “thousands of these aliens were starving,” he said,

they were interned “under the inspiration of the sentiment of compassion.”

Justifying the mass layoffs of nonAnglos, he said “the labour market was glutted

and there was a natural disposition to give the preference in the matter of

employment to our own people.”47

AngloProtestant authorities

were certainly concerned about poverty among unemployed “aliens.” However, their

concern was not for the poor’s welfare. Their goal was to protect capitalism

from a feared socialist upheaval led by radicalised foreign workers. Slave

labour camps also helped shelter corporations from the economic hardships of

Canada’s

recession.

Opposing Capitalist, Religious and Military Slavery

Why did Canadian power brokers see east

Europeans as such a threat to the established order? The anticapitalist,

liberation movements that swept through central and eastern Europe between 1905

and 1907, captured the imagination of many Ukrainians in Canada. This community

was then bolstered by politicised émigrés fleeing Czarist repression. (See

pp.38-39.) By 1906, socialist Ukrainians were printing anticapitalist tracts

and building radical, multi-ethnic organisations like the Industrial Workers of

the World and the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC).

The SPC’s largely Anglo-Saxon leadership rigidly

rejected all efforts to gradually reform capitalism. Instead, they had an

“impossibilist” ideology that demanded total and immediate revolution.

Underlying this struggle, the SPC saw “one issue...as the basis for all

political organization,” namely, the “abolition of the present system of wage

slavery.”48

Slavery tropes were also central to the rhetoric

of Ukrainian socialists. In 1907, the first issue of Chevron Prapor (“The

Red Flag”)—a Winnipeg-based newspaper for Ukrainians within the SPC—described

its purpose as leading a struggle against “injustice, exploitation and slavery.”49 By

1914, Ukrainian socialists in Winnipeg, although by then freed from the

confining ideology of the SPC, were still bound by antislavery rhetoric, saying

“only he who works for the emancipation of the enslaved masses is a true

patriot.”50

Socialist Ukrainians saw their ethnic group as

an enslaved segment of Canada’s working class, held in place by the inherently

exploitative capitalist system. As Martynowych has noted, by 1913 radical

Ukrainian socialists were saying that

“Ukrainian immigrant labourers, especially those who

worked on railway construction, in the forests and in the mines, were little

more than ‘free white slaves’ and ‘white niggers’...in the capitalist system.”51

These references to “free white slaves” and

“white niggers” are from Robotchyi Narod (Working People), the

Ukrainian Social Democratic Party’s paper in Winnipeg.

So, even before

east Europeans were literally enslaved in Canadian internment camps,

radical Ukrainians were using metaphoric links that tied corporate-run

work camps to slavery.

Many socialist Ukrainian Canadians, swayed by

Ukraine’s Radical Party, saw religion as a powerful form of captivity. These

activists, Martynowych said “were free of the cultural fetters imposed on the

individual in traditional peasant societies.” They “articulated a social and

political orientation based on anticlerical, socialist and populist principles”

because

“the higher clergy in

Galicia (Catholic) and in

Bukovyna (Orthodox) acted as the instrument of foreign ruling classes, while

most members of the lower clergy remained indifferent to the plight of the

peasantry.”52

In 1911, Ukrainian socialists in Winnipeg held a

“Free School” with talks on “female

emancipation, the Inquisition, the relation of churches to the institution of

slavery, [and] the theories of Darwin....”53

These Ukrainians were no doubt inspired by

Marxist metaphors that decried religion as “the opium of the people,” as well as

by slavery tropes in the Communist Manifesto of 1848, which infamously

said that “proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.” Marx and Engels

also mixed metaphors and similes about workers, soldiers and slaves, saying

“Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are

organised like soldiers.... Not only are they slaves of the bourgeois class, and

of the bourgeois State; they are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine.”54

Ukrainian Canadian radicals took these tropes to

heart. In 1917, Robotchyi Narod asked: “Do you realize that Ukrainian

workers occupy the lowest position in this capitalist prison?”55 While

“prison” captures the idea of a structure for inmates, it also encloses,

metaphorically, the idea of “wage slaves” trapped by class structures. The

Czar’s empire was also described in terms of captivity. After the events of

February 1917, Ukrainian socialists held a mass meeting at the Winnipeg Opera

House and sent their “fraternal greetings” to “Russian worker-revolutionaries”

to celebrate “world victory... over autocratic tsarism and the break-up of the

prison-house of nations.”56

But Ukrainian Canadian socialists were not

content to merely use rhetorical devices about prisons and slavery as an escape

valve to express liberating, anticapitalist ideas. They took action by pushing

for specific changes to Canadian government policies. For instance, radical

Ukrainian leftists called for such enlightened goals as an eight-hour work day,

a minimum daily wage, voting rights for all men and women over 21, social

insurance for seniors and the disabled, and the abolition of child labour.57 These

demands were shocking to Canada’s capitalist elites, who framed such socialist

ideals as unthinkably dangerous, if not criminally insane.

Ahead of their time, Ukrainian social democrats

strove for a more equitable society. They wanted a world where manufacturing

would meet everyone’s needs, not just amass huge profits for the privileged

few. It was, and still is, a revolutionary ideal. But, as Martynowych points

out, although “their ultimate goal...was revolutionary, their methods were

moderate.” The reforms that they demanded were meant to further “the evolution

of capitalism” and create “preconditions for a smooth and orderly transition to

socialism.”58 They pursued

gradual social change through education, peaceful protest, labour actions and

electoral politics, not by any kind of violent overthrow of the Canadian

government.

During WWI, Ukrainian radicals joined other

socialists in opposing the forced labour that was imposed by military

conscription. They did not do this to support the imperial Austro-Hungarian

regime that controlled Ukraine. They opposed the draft because WWI—which was

being pushed by governments, churches and other captive civil-society

organisations—was killing working class people around the world. Seeing that

competing imperialist powers were using workers as pawns in a “Great Game” to

profit elites, Ukrainian socialists rejected conscription.

They paid sorely for such views. Even after

internees were released on parole from prison camps, they could be arrested

again just for attending events to talk about military conscription. For

example, in June 1917, when the Ukrainian branch of the Social Democratic Party

in Toronto met to discuss the draft, police stormed in and arrested 80 of them

for violating their parole conditions. Just a week earlier, an angry mob of

several hundred WWI veterans had attacked a similar event, beating organisers

and then marching off in military formation. Toronto police stood by and did

nothing to stop the violence.59

This was typical. Canadian authorities exerted control not only by

rendering dissidents captive in forced labour camps, but by turning a blind eye

when vigilante thugs assaulted peaceful, antiwar activists.

Caged by the Fear of Captivity

While Canada’s elite used mass

internment to extract cheap labour and to contain the spread of radicalism,

whole communities were effectively held in place by fear.

During WWI, Canada had 88,000

registered “enemy aliens,” mostly Ukrainians. If caught without their

official, identity papers, they could be interned immediately. “Police conducted

regular roundups in immigrant neighbourhoods,” said Ian Angus, founder of

Canada’s Socialist History Project, “arresting every man who could not produce a

registration card.”60

But, not all “enemy aliens” had to register with

authorities. There were more than 393,000 Germans and at least 129,000

Austro-Hungarians in Canada.61

This was six times more than all of those who were forced to register, which

included Turks, Bulgarians and others. When registration centres were set up

under RCMP supervision in Canada’s largest cities, only those enemy aliens

living within 20 miles had to register. After all, the state only wanted to

control urban “aliens,” especially single, jobless, working-class

Ukrainian men.

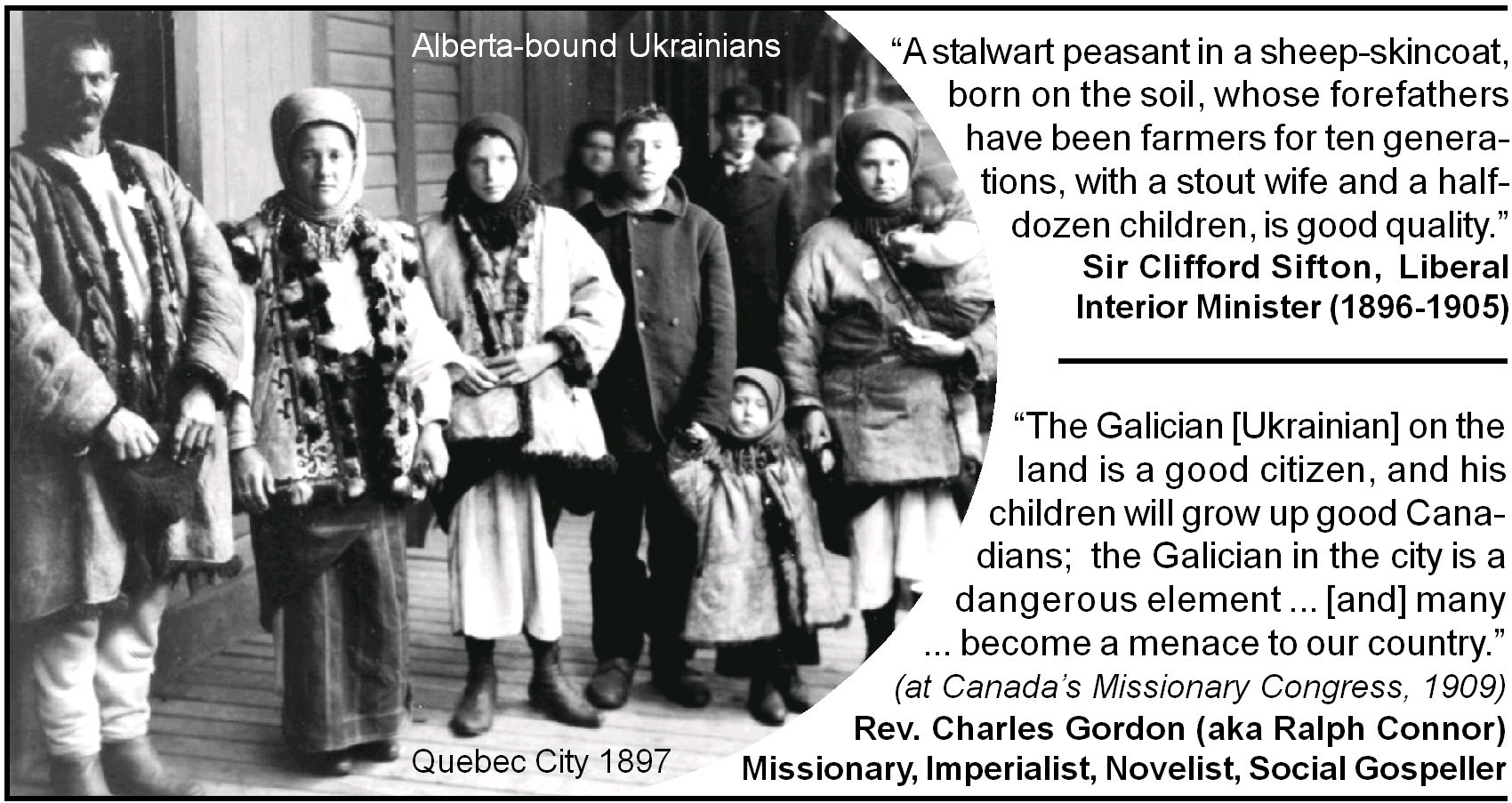

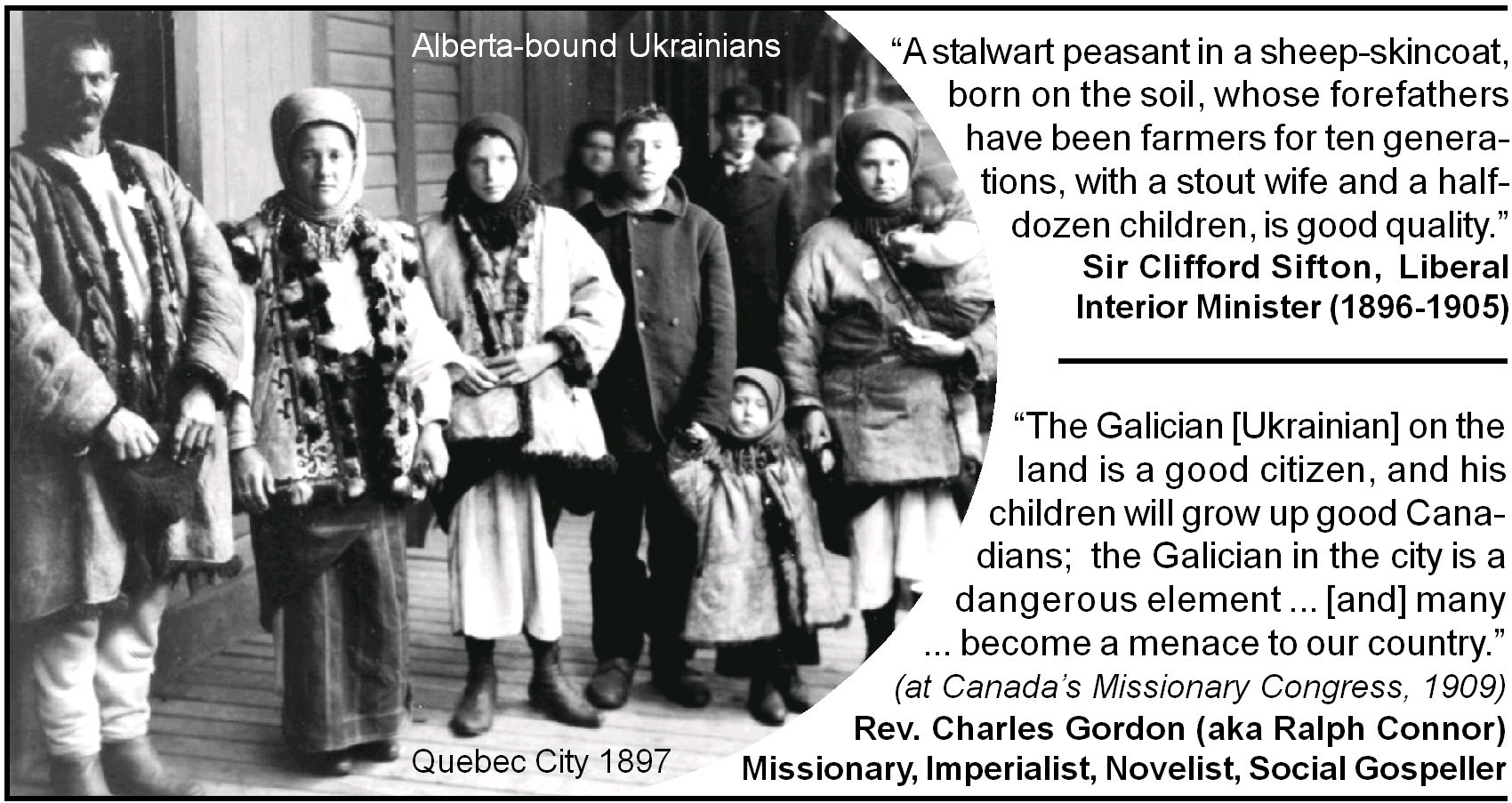

Even before WWI, it was a well-

established myth that urban Ukrainians were a grave threat to Christian

Canadian values. This meme in the paranoid folklore of Protestant elites was,

for instance, spread at the five-day “National Missionary Congress” which drew

4,000 to Toronto’s Massey Hall in 1909.62

Addressing the threat of nonAnglo-Saxon “foreigners,” that he said “really

constitute our problem,” was militant Social Gospeller Rev. Charles Gordon,

Canada’s most popular novelist. Referring to Ukrainians as Galicians (for

Galicia was held captive by Austria-Hungary), he said that while “the Galician

on the land is a good citizen, and his children will grow up good Canadians; the

Galician in the city is a dangerous element.”63

After warning that “many of the settlers who

drift into the cities become a menace to our country,” Gordon asked, “What are

we as Christian Canadians and as Christian

Churches to do?”64 The

problem, he said, was that

“we need them for our work. They do work for us that

Canadians will not do ...and were it not for the Galicians and... [other]

foreign peoples...we could not push our enterprises in railroad building and in

lumbering and manufacturing to a finish.”65

Historian Adam Crerar noted

that the “threat of internment—and the sense of rejection by Canadian

society...—was felt by all who were at risk.”66 This

was recognised in a 1916 BC police report on the reduced labour militancy among

miners. “From a police point of view, there has been less trouble amongst them

since the beginning of the war than previously,” said a chief constable. “[T]he

fact that several of them were sent to internment camps at the beginning of the

war seemed to have a good effect on the remainder.”67

Despite its targeted approach, internment had a

chilling effect on whole communities. The registry of “enemy aliens” was also a

turning point in Canada’s surveillance of radicals. Once registered, aliens had

to report to authorities at least once a month. As Arthur Meighen, Minister of

the Interior and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, reported in March 1919, the

government’s Dominion-wide register

“increased in completeness...until we...had

practically a record of all the alien enemies in the country. A close watch was

kept, and is kept, of their occupations, and activities, and they are all pretty

well followed.”68

Within two weeks of this

chilling statement, Toronto

police rounded up three socialists—two Germans and a Russian—who authorities

publicly claimed were “the nucleus of a Communist Party” in Canada. After

holding them incommunicado for a whole month, one was sent to an internment

camp, and another was held in jail. Both were later deported to the US. In

discussing this case with the Toronto Times, the city’s Inspector

of Detectives, George Guthrie, stated that police had obtained

“a list of possibly 1000 men and women, the

majority...of foreign birth, who were actively participating in this Bolshevist

agitation. We know also their names and where they are employed. At any moment

they can be picked up, and from now on they will be closely watched.”69

Publicising this blacklist’s

existence, with the threat of arrest, sent a “Red Chill” through activist

communities. The fear of being listed must have scared activists and

nonactivists away from radicals, their literature and events. Knowing that

police had data on jobs, worsened the intimidation. Livelihoods could be taken

away, not just freedoms of movement, association, assembly and expression.

The biggest threat hanging over

people’s heads was that they could be “picked up” “at any moment” and caged at a

remote slave labour camp. By wielding this blunt instrument of terror, the

government created fear not only among radical foreign activists, and their

political groups, but throughout their ethnic communities. As one RCMP constable

of Ukrainian origins informed his Ottawa bosses in 1941, the community had long

lived “in fear of the barbed wire fence.”70

But

the threat of captivity went far beyond the boundaries of ethnicity. People

across Canada got the message that authorities would not tolerate those who

dared to entertain radical socialist ideas. Internment was therefore part of a

cost-effective social-control program to render Canadians captive by fear.

Threatened the loss of jobs, civil rights and/or physical freedoms was an

effective weapon for scaring people away from even exploring ideas that elites

considered a potential threat to “peace, order and welfare” of Canada.

But

the threat of captivity went far beyond the boundaries of ethnicity. People

across Canada got the message that authorities would not tolerate those who

dared to entertain radical socialist ideas. Internment was therefore part of a

cost-effective social-control program to render Canadians captive by fear.

Threatened the loss of jobs, civil rights and/or physical freedoms was an

effective weapon for scaring people away from even exploring ideas that elites

considered a potential threat to “peace, order and welfare” of Canada.

Crazed by the fear of a threat

to the status quo and the loss of their privileged position within the

established order, Canada’s

political, economic and religious leaders developed a phobic response to radical

socialism. They reacted by using WWI as a pretext for wars of containment both

at home and abroad. Domestically, internment was used to contain supposed

enemies of Canada, largely from eastern Europe. On the foreign front, Canada

joined the 1919-1921 war to stop the Russian revolution, contain its spread and

threaten similar uprisings around the world.

In spreading their antiRed

paranoia, Canadian elites built upon existing social narratives of racist

superiority and cultural narcissism that had long captured the prevailing

Eurocentric mindset of the

Peaceable

Kingdom.

As a result, mainstream society remained entranced by a mass delusion that

perceived Canada’s imperial brand of warmongering xenophobia as if it were a

liberating effort to promote progressive Christian values.

References/Notes

70. RCMP, “Report re: 8th National Convention of

Ukrainian National Federation of Canada and Affiliated Societies,” Aug. 25-31,

1941.

Cited by Luciuk 2001, Op. cit.

This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in