This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in

Captive Canada:

Renditions of the Peaceable Kingdom at War,

from Narratives of WWI and the Red Scare to the Mass Internment of Civilians

Issue #68 of

Press for Conversion (Spring 2016),

pp.22-29.

Press for Conversion! is the magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).

Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this

coupon,

or use the paypal link on our webpage.

If you quote from or

use this article, please cite the source above and encourage people to

subscribe. Thanks.

Here is the pdf version of this

article as it appears in Press for Conversion!

Religious

Guardians of the Peaceable Kingdom:

Winnipeg’s Key Social-Gospel Gatekeepers of Canada West

By Richard Sanders, Coordinator,

Coalition to

Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT)

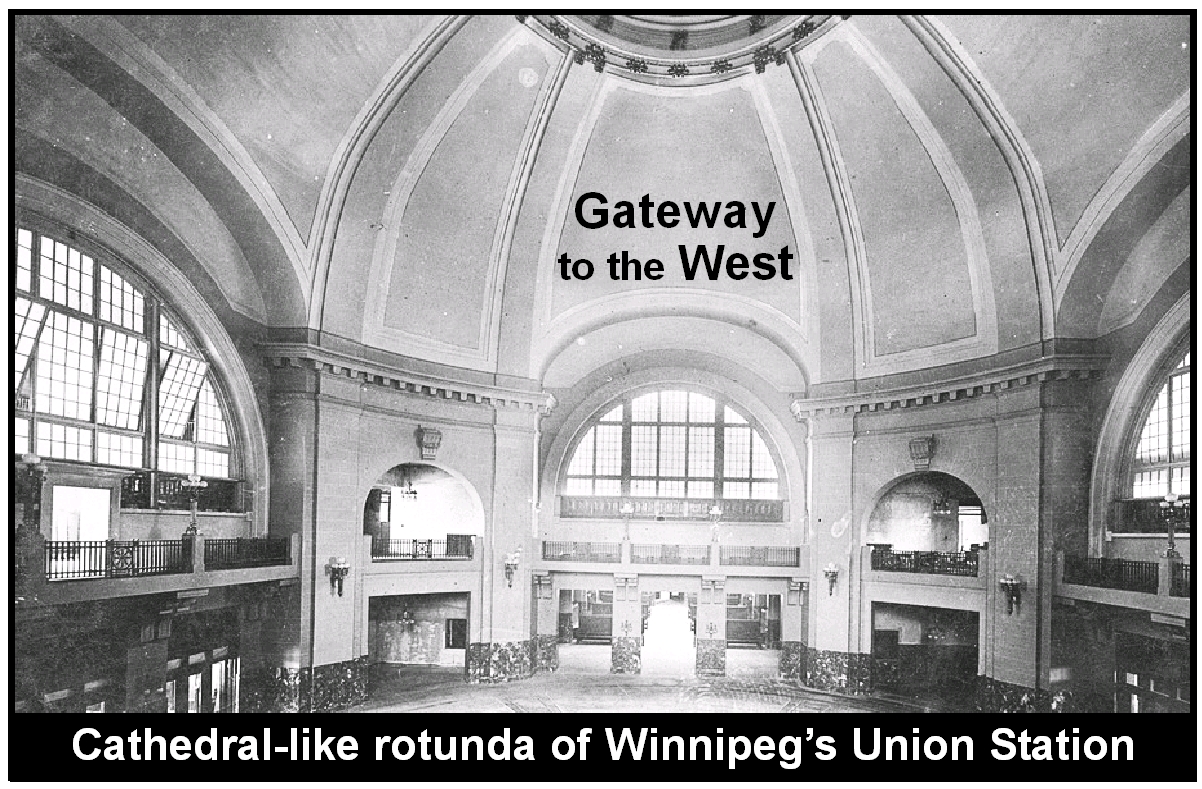

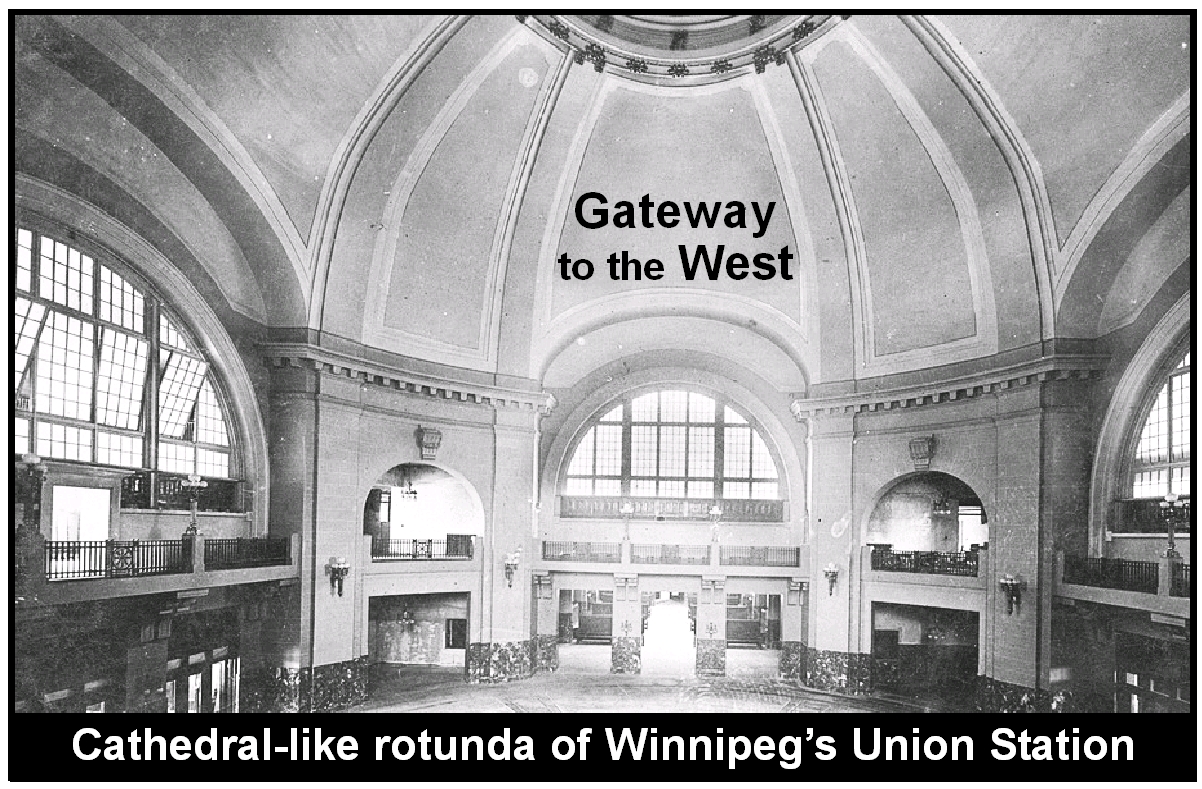

With the

ethnic cleansing of Indigenous peoples from the prairies and the arrival of the

railway in the 1880s,

Winnipeg’s

train station was the “Gateway to the West.” By the onset of WWI, over a million

newcomers had been moved in to settle western Canada.

While Canadian churches maintained their

blissful silence about the imperial land grab, the mass confinement of Indians

on reserves, and the cultural genocide imposed by Christian residential schools,

they quickly created morally indignant narratives to decry the rapid influx of

nonAngloSaxons. In reaction to these immigrants, who they considered inferior,

some of

Winnipeg’s

most prestigious clergymen took it upon themselves to become the civil-society

“gatekeepers” of fortress

Canada.

These progressives were soon locked in a battle against the gate-crashing

“aliens” who had penetrated the walls of their sacred

Peaceable

Kingdom.

With brave and heroic tales about the

progressive spread of enlightened British culture across the untamed West,

mainstream Protestant churches saw themselves as the vanguard of a grand

imperial project called

Canada. In

waging their cultural war against First Nations, these self-appointed guardians

of national security created popular myths about their valiant mission to

protect Canada from savage attacks by religious, political and racial inferiours.

Later, when confronted by unwanted immigrants with religious beliefs and

political loyalties that competed with their own, AngloProtestants changed the

sights of their xenophobic narratives and worked themselves into a new, moral

frenzy.

To convey their collective panic, they

filled a host of traditional cultural vessels—from sermons, college lectures,

missionary tracts and other, more popular religious fictions, like novels—with

cautionary tales about strangers. These narratives were like church bells

sounding warning of an impending peril. East Europeans—seen as spiritually

backward, unassimilable and politically radical—were seen as a worrisome new

threat by respected gatekeepers of

Canada’s

Christian civilisation.

In their propaganda war against unwanted

foreigners,

Winnipeg

gatekeepers demonised a certain class of “enemy aliens.” This was soon followed

by their mass captivity in WWI-era, labour camps.

Invading the Kingdom

Between 1871 and 1911,

Canada’s

prairie population grew by 1.3 million: 375,000 in Alberta, 492,000 in

Saskatchewan and 430,000 in Manitoba.1 Most

settlers came west via Winnipeg on Canada’s new railroad. They were largely

Anglos, especially in Manitoba where 64% were British. While Germans and

Scandinavians made up 15% of the total, Francophones were only 6%. During this

preWWI spurt, the dominance of northwest Europeans began to decline. For

example, the prairies’ British population fell from 86% in 1901 to 77% in 1911.

During that same decade, east Europeans

became far more visible on the prairies.

Manitoba’s

Slavic community of Austro-Hungarians, Russians and Poles, almost quintupled

from 12,760 in 1901, to 59,230 in 1911. This increased their presence from 5% to

13% of the total population.2

Most of these Slavs were Ukrainian. About 170,000 of them had entered Canada

between 1891 and 1914, with a record number of 22,000 arriving in 1913,3 on

the very eve of WWI.

But gates are not just entry points, they

are also exits for expelling the unwanted. While between 1903 and 1908

Canada

deported 1,401 “undesirables,” 1,748 were thrown out in 1909 alone. This

followed an influx of aliens fleeing Czarist repression after the Russian

revolution of 1905-1907. (See pp.36-39). This record number of deportations was

not matched until 1914. During WWI, 5,943 were unceremoniously thrown from our

gates.4

But gates are not just entry points, they

are also exits for expelling the unwanted. While between 1903 and 1908

Canada

deported 1,401 “undesirables,” 1,748 were thrown out in 1909 alone. This

followed an influx of aliens fleeing Czarist repression after the Russian

revolution of 1905-1907. (See pp.36-39). This record number of deportations was

not matched until 1914. During WWI, 5,943 were unceremoniously thrown from our

gates.4

By war’s end,

Canada was

engaged in “the deliberate and systematic deportation of agitators, activists

and radicals,” said historian Barbara Roberts. The “threat they posed was not to

the people of Canada” but to “vested interests such as big business,

exploitative employers, and a government acting on behalf of interest groups.”

Deportees included opponents of WWI and conscription, militant labour activists

and radical socialists. The excuse for deporting them was often that, as

indigents, they might need state assistance.5

Information Gateways

Winnipeg

clergymen, Charles Gordon, J.S.Woodsworth and J.W.Sparling, were on the front

line of a culture war to maintain the supremacy of Canada’s AngloProtestant

civilisation. Although they did not control the physical gates through which

aliens entered and exited Canada’s gates, these Social Gospellers did exert

control over the flow of information about aliens.

Social Gospellers were gatekeepers in the

sense invoked by Kurt Lewin, the Jewish-American father of social psychology who

fled

Germany

in 1933. In 1943, Lewin published his gatekeeping theory to explain how

individuals controlled the flow of commodities and data within social systems.

Interestingly, he was influenced by political scientist Harold Lasswell’s 1920s

research on the decision-making processes used to create WWI propaganda.

Lewin said that his gatekeeping model could

be used to understand social organizations and newsrooms. Since then, scholars

in many disciplines have developed Lewin’s gatekeeping theory to analyse how

data is filtered through various systems to construct social realities.6

As mass communications professors Pamela Shoemaker and Tim Vos have

explained:

“Gatekeeping is the process of culling and

crafting countless bits of information into the limited number of messages that

reach people each day.... [It] determines not only which information is

selected, but also what the content and nature of the messages, such as news,

will be.”7

Gatekeeping theory can explain how Social

Gospellers used ethnocentric religious and political filters to select data

about aliens that they then crafted into narratives to sway the minds of their

parishioners, politicians and the public at large.

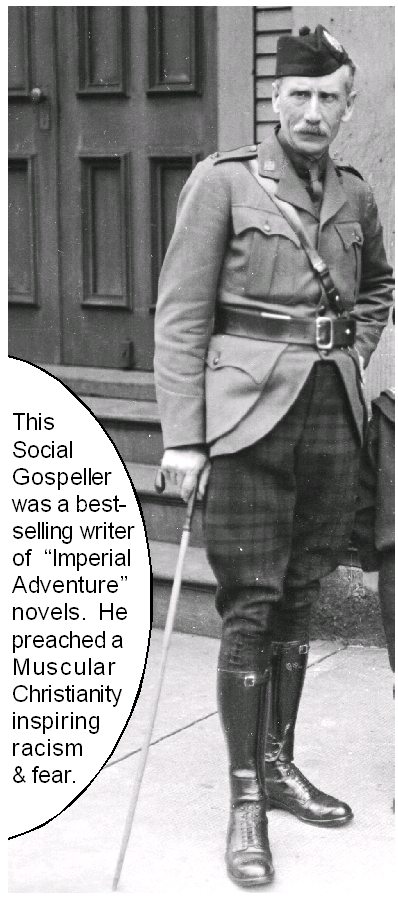

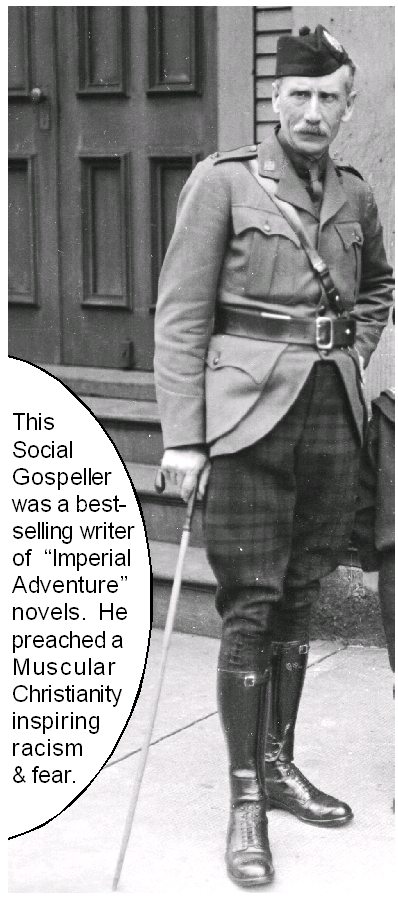

Rev. Charles Gordon, aka “Ralph Connor”

The leading populariser of the Social

Gospel was best-selling author, Rev. Charles Gordon. His first three

swashbuckling novels sold over five million copies. The “sole purpose” of his

first book, he said, “was to awaken my church …to the splendour of the mighty

religious adventure being attempted by the missionary pioneers” in Canada’s

west.8

Using the alias Ralph Connor, Gordon was “the

most successful practitioner …in the world” of a genre called “imperial

adventure fiction.”9 His

thirty novels also captured the spirit of so-called “Muscular Christianity,” a

Victorian movement stressing a mix of pious athleticism with virile

masculinity. It was hardcore Christian evangelism on imperial steroids.

Using the alias Ralph Connor, Gordon was “the

most successful practitioner …in the world” of a genre called “imperial

adventure fiction.”9 His

thirty novels also captured the spirit of so-called “Muscular Christianity,” a

Victorian movement stressing a mix of pious athleticism with virile

masculinity. It was hardcore Christian evangelism on imperial steroids.

In The Social Uplifters: Presbyterian

Progressives and the Social Gospel in Canada, Brian Fraser—a Church History

professor at Vancouver’s School of Theology—praised Gordon as one of the “central figures in articulating and

implementing a social Christianity.”10 What

he does not explain is that Gordon used his literary pulpit to preach an

ethnocentric xenophobia that spread fear and hatred.

An avid imperialist, Gordon transformed fictive

Mounties—like Corporal Cameron—into graven macho images of biblical dimensions.

Mounties were to be idolised for defending what Gordon called “the ‘pax

Britannica’...of Her Majesty’s dominions in this far northwest reach of Empire.”11 Gordon’s

cartoonified cops, and their tough missionary helpmates, teamed up in novels

about the Northwest Rebellion. In Gordon’s racist mind, the villain’s role was

played by “thousands of savage Indians, utterly strange to any rule or law”12 who

were “thirsting for revenge upon the white man.” His narrative saw the

“insatiable lust for glory formerly won in war” as the “fiery spirit of the red

man, long subdued by those powers that represented the civilization of the white

man.”13

Gordon’s words captured the image of the Métis

as “ignorant, insignificant, half-tamed pioneers of civilization,” with their

leader, that “blood-lusting,” “vain and empty-headed Riel” who stirred up

“horror unspeakable in the revival of that

ancient savage spirit which had been so very materially softened and tamed by

years of kindly, patient and firm control on the part of those who represented

among them British law and civilization.”14

Gordon not only reflected the prevailing racism

of his time, he promoted, shepherded and covered up the savage cruelty of those

who saw themselves as being on the vanguard of a physically, culturally, morally

and spiritually advanced race.

Gordon’s zeal for assimilation was channelled

through a morality tale, The Foreigner (1908). His urgent plea for robust

missionary action conjures up the dire threat of depraved Slavs who had

penetrated Canada via Winnipeg’s gates. His allegory focuses on the rescue of

what he calls “a poor, stupid, Galician [Ukrainian] woman with none too savoury

a reputation.” Entering stage right, preparing to save the day, were the heroic

churches:

“Many and generous were the philanthropies

of Winnipeg,

but as yet there was none that had to do with the dirt, disease and degradation

that were too often found in the environment of the foreign people. There were

many churches in the city rich in good work ...but there was not yet one whose

special duty it was to confer and to report upon the unhappy and struggling and

unsavoury foreigner within their city gate.”15

Gordon molded this book’s hero, Brown, after

himself, an AngloProtestant missionary trying to uplift aliens in Winnipeg’s

North End. Gordon and Brown were both trapped by an overpowering obsession: to

Canadianise and Christianise foreigners. As Brown put it, he wanted “to make

them good Christians and good Canadians, which is the same thing.”16

Through Brown, Gordon articulated the common

Canadian phobia that east Europeans could not be absorbed quickly enough into

the vastly superiour AngloProtestant culture. This process of moral and social

absorption required “uplifting” inferiour races and cultures with what are now

commonly called “Canadian values.” As Brown saw it, east Europeans

“here exist as an undigested foreign mass.

They must be digested and absorbed into the body politic. They must be taught

our ways of thinking and living, or it will be a mighty bad thing for us in

Western

Canada.”17

But the novel’s secondary

hero—French—expressed the public doubt that Slavs could ever be instilled with

the values of

Canada’s

advanced civilisation. Calling them “a score of dirty little Galicians,” he says

“You go in and give them some of our Canadian ideas of living..., and before you

know they are striking for higher wages and giving no end of trouble.”18

But Gordon was no mere novelising

missionary, he was also a powerful mediator in “industrial disputes…on behalf of

the Dominion government.” While working for the government to bridge conflicts

between huge corporations and radical unions, he exchanged many cordial letters

with the Liberal’s Labour Minister, MacKenzie King.19

Gordon also “counted national leaders such as Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Theodore

Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson among his readers and friends.”20

To Gordon,

Canada was not

only a faithful servant of British imperialism, it was also part of a divine

empire of White nations led by God that was marching towards a glorious, global

conquest. As he told thousands gathered at the national missionary congress in

1909, Canada was:

“part of a Greater Empire...that knows no

boundary all round this great world, ...an Empire led on to the conquest of the

world not by any human mind or by any human hand, but ...by the great God

Himself. For this conquest

Canada must

gird herself now; and if ...Canada

is not able to maintain those high traditions for godliness... Canada [will]

fail of her destiny,...[to] keep pace with the greater Anglo-Saxon nations who

are marching on to evangelize the world.”21

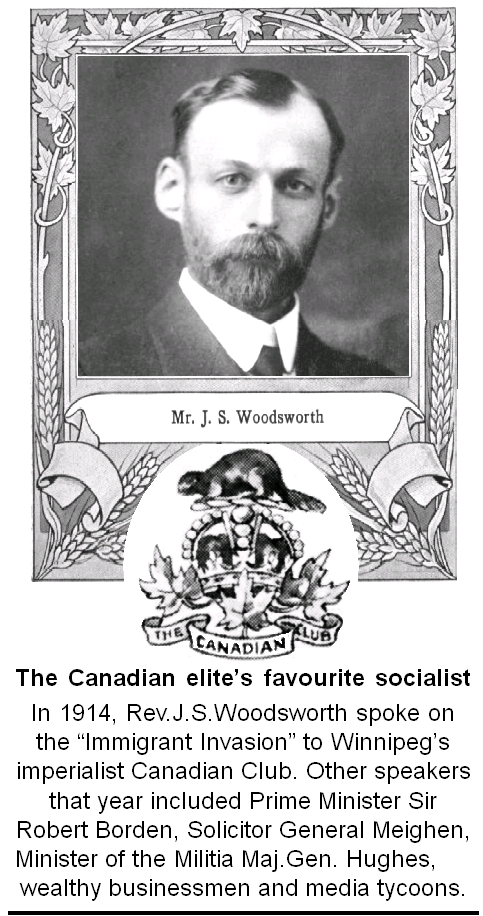

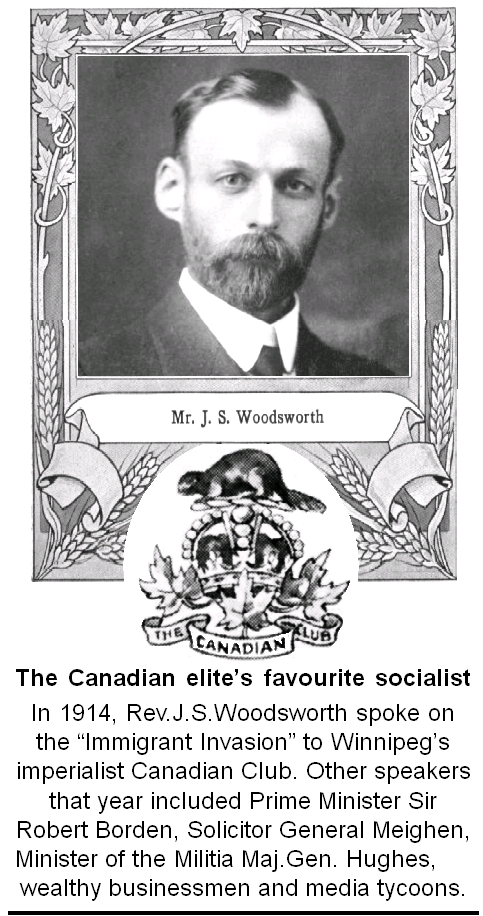

Rev. James Shaver (J.S.) Woodsworth

Winnipeg was

the setting for an activist minister named James Shaver (J.S.) Woodsworth

(1874-1942). This Methodist Social Gospeller became the MP for Winnipeg North

Centre (1921-1942), initially for the Independent Labour Party and then later

for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Woodsworth was a key founder

and first leader of the CCF (1932-1942), which joined with the Canadian Labour

Congress in 1961 to form the the NDP.

Many who still revere Woodsworth have no

idea that before WWI, he led the way in fearmongering attacks against unwanted

foreigners. In 1909, one year after Charles Gordon’s novel, The Foreigner,

Woodsworth released an utterly racist tome called Strangers Within Our

Gates. Published by the

Methodist

Church’s Missionary Society, it was one of Canada’s most influential Social

Gospel tracts. Rev. Charles Gordon loved it. “If you want to know something

about Canada and the perils of Canada,” Gordon told the huge crowd at Canada’s

1909 Missionary Congress, “get that very excellent little book of Mr.

Woodsworth’s, Strangers Within our Gates,... and you will find it is full

of instructive information.”22

Many who still revere Woodsworth have no

idea that before WWI, he led the way in fearmongering attacks against unwanted

foreigners. In 1909, one year after Charles Gordon’s novel, The Foreigner,

Woodsworth released an utterly racist tome called Strangers Within Our

Gates. Published by the

Methodist

Church’s Missionary Society, it was one of Canada’s most influential Social

Gospel tracts. Rev. Charles Gordon loved it. “If you want to know something

about Canada and the perils of Canada,” Gordon told the huge crowd at Canada’s

1909 Missionary Congress, “get that very excellent little book of Mr.

Woodsworth’s, Strangers Within our Gates,... and you will find it is full

of instructive information.”22

Woodsworth opened his text with two Old

Testament quotations that reveal a grave contradiction in the Social Gospel’s

approach to “strangers.” The first passage exhorts people to treat the “stranger

that sojourneth with you” as if he was a “homeborn” and to “love him as thyself”

(much as Jesus is said to have urged “love thine enemy”). Woodsworth’s second

verse however is a rallying cry to absorb “strangers” and their children, into

one’s religion:

“Assemble the people, the men and the women

and the little ones, and thy stranger that is within thy gates, that they may

hear, and that they may learn, and fear the Lord your God.”23

This schema of loving indoctrination was an

ideological framework within which Woodsworth and other Social Gospellers saw

their sacred mission to civilise nonbelievers. Bound by this holier-than-thou

attitude, Canadian “gatekeepers” felt a pious duty to impose their religious

belief systems on the aliens in their midst.

The preface to Woodsworth’s treatise on

assimilation, introduces the “problem” of foreigners by humbly stating that

“this little book is an attempt to introduce

the motley crowd of immigrants to our Canadian people and bring before our young

people some of the problems of population...”24

The very title of Woodsworth’s “little book”

conjures up the image of Canada as a gated community threatened by troublesome outsiders. His virulence

in expressing this phobia may surprise many progressives who still idolise

Woodsworth as the ground-breaking leader of progressive Canadian politics.

Despite all his achievements as activist, organiser, politician and architect of

Canada’s social democratic movement,

Woodsworth held the same sort of racist and patronising attitudes of religious

and cultural superiourity that plagued those on Canada’s extreme right.

For instance, Woodsworth’s book Strangers

Within Our Gates, included vile stereotypes of Indians. Whatever his

reasoning, Indigenous peoples should never have been forced into the confines of

his book on immigrants. The strange idea that Aboriginals are “foreign” to

Canada was accepted within Woodsworth’s church. In 1906, Canada’s Methodist

Church divided its Missionary Society into two departments: “home” and

“foreign.” The work of Christianising, civilising and Canadianising native

people was placed in the Methodist’s foreign-mission department.25

Woodsworth lumped “Indians” and “Negroes” into

one chapter of his book because, he said, “they are so entirely different from

the ordinary white population.”26 And,

he segregated them from other “races” because of their “savagery.”27

One crucial fact that does tie these two

peoples together, but which Woodsworth blindly left unmentioned, is that both

endured centuries of state-sanctioned slavery at the hands of Canada’s

supposedly-civilised west European Christians. By forcing them into his book on

alien strangers, and crudely black-listing them as “savages,” Woodsworth added

insult to a long- ignored historic injury.

In contrast to his disdain for Indians and

Blacks, Woodsworth had the highest regard for Anglos. He considered the first

English in North America to be “pilgrims” and colonists, not immigrants.

“They came to an unexplored wilderness inhabited only by savages,” he explained.

“They had to create a civilization.”28

After hurling a variety of racist slurs at

Blacks, Woodsworth happily noted that “We may be thankful that we have no ‘negro

problem’ in

Canada.” He

concluded with this hopeful note: “Many negroes are members of various

Protestant churches, and are consistent Christians.”29

Woodsworth’s hateful view of the so-called

“Oriental Problem,” revealed his dogged fixation on religion as a filter for

judging aliens. Woodsworth’s section on “Chinamen” relied on a 15-page excerpt

from what he called “a splendid little book” by Rev. J.C.Speer, a missionary and

Methodist Minister like himself. Speer’s racist screed on “the heathenized

nature of the Chinaman,” declared that even “the baldest kind of congregational

service in a Christian church” is “far above and beyond” Chinese “heathen

worship.” Speer decried “the Chinaman” as a “darkened heathen” and a

“dark-minded heathen” who “bows down to demons.”30

Woodsworth also hurled vile insults at

newcomers from the

Middle East, calling them “one of the least desirable

classes of our immigrants.” The worst among them, he said, were Syrians who came

mostly from “Mount Lebanon...which

the Christian powers protect against the ‘unspeakable Turk.’” As evidence,

Woodsworth turned to J.D.Whelpley’s The Problem of the Immigrant (1905)

which calls Armenians and Syrians “a most undesirable class” whose “intellectual

level is low.” Woodsworth also cites another American, Dr. Allan McLaughlin,

who wrote in 1905 that “these parasites from the near East” are a “distinct

menace” who “lie most naturally and by preference.”31

(In 1908, McLaughlin was an US “colonial bureaucrat” in the Philippines

but by 1918 he was the US Assistant Surgeon General.32)

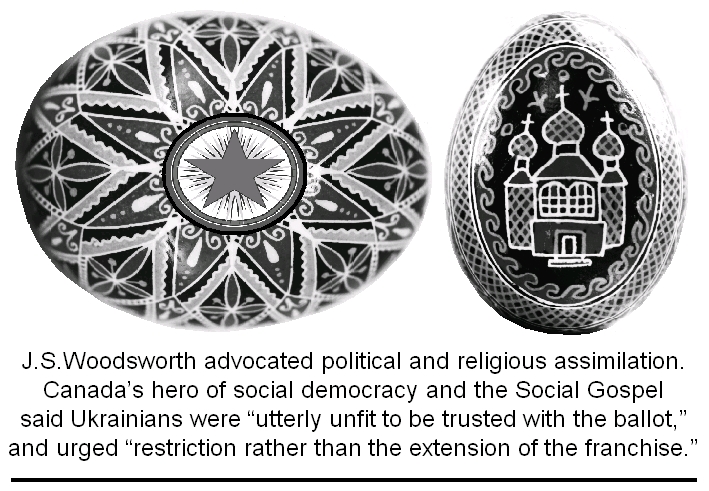

Perhaps the most slandered immigrants in

Woodsworth’s overtly racist book, Strangers Within Our Gates, were east

Europeans. He saw them as so politically inferiour that he urged the Canadian

government to “reform” matters by removing their right to vote. In his chapter

on “Assimilation,” Woodsworth insulted Ukrainians by saying “the vote of one of

these foreigners ‘kills’ the vote of the most intelligent Canadian!”33 Continuing

his anti-democratic polemic, Canada’s social-democrat crusader sermonised that:

“Peoples emerging from serfdom, accustomed

to despotism, untrained in the principals of representative government, without

patriotism...are utterly unfit to be trusted with the ballot... It is as absurd

as it is dangerous to grant to every newly arrived immigrant the full privilege

of citizenship.... The next reform should look to restriction rather than the

extension of the franchise.”34

Woodsworth’s policy proposal was ahead of its

time. It was not until nine years later that the Wartime Elections Act

“effectively disenfranchised most Ukrainians in Canada.”35

Prime Minister Borden’s government was concerned that conscription, introduced

in May 1917, would prove so unpopular that the Conservatives might lose the next

election. So, all “enemy-aliens” naturalised after March 31, 1902, lost their

right to vote, unless they had a close relative on active duty. Although the

Act also disenfranchised pacifists and conscientious objectors, it extended the

vote to women in the military, and to those with enlisted sons, husbands or

brothers.36 This was a

victory for those “progressive” suffragettes who had long argued

“that they needed the vote...to help offset

the detrimental effect which they claimed immigrants were having on prairie

society. Women’s groups pushing for the vote argued that certainly they deserved

the vote if ‘ignorant foreigners’ had it.”37

Woodsworth excelled at propagating this image of

“ignorant” east Europeans. Polish immigrants, he said, were “far from the best

class. They are poor, illiterate, and with a code of morals none too high.”38 As

for Austrians (who were mostly Ukrainians) and Russians, he said the:

“majority [are] illiterate and

superstitious; some of them bigoted fanatics, some of them poor, dumb, driven

cattle, some intensely patriotic,...some anarchists—the sworn enemies alike of

Church and State.”39

Woodsworth’s section on Ukrainians was penned by

journalist Arthur R. Ford of the Winnipeg Telegram. Ford, the son of

Methodist Minister James Ford, described “how difficult the problem of

Canadianizing” them could be. Warning that Ukrainians were “crowding to our

shores,” he revealed “the cold fact” that 125,000 had already arrived, and that

40,000 were within Manitoba’s gates. He then remarked that Canadians had “so

low an estimation” of them “that the word Galician is almost a term of

reproach.” He also associated Ukrainians with violence and criminality by

saying that their

Woodsworth’s section on Ukrainians was penned by

journalist Arthur R. Ford of the Winnipeg Telegram. Ford, the son of

Methodist Minister James Ford, described “how difficult the problem of

Canadianizing” them could be. Warning that Ukrainians were “crowding to our

shores,” he revealed “the cold fact” that 125,000 had already arrived, and that

40,000 were within Manitoba’s gates. He then remarked that Canadians had “so

low an estimation” of them “that the word Galician is almost a term of

reproach.” He also associated Ukrainians with violence and criminality by

saying that their

“unpronouncable names appear so often in

police court news, [and] they figure so frequently in crimes of violence that

they have created anything but a favourable impression.”40

Calling Ukrainians “illiterate and ignorant,”41 he

opined that “Centuries of poverty and oppression have, to some extent,

animalized him. Drunk, he is quarrelsome and dangerous.”42

In his book’s preface, Woodsworth said he “was

glad to have had the co-operation of Mr. A.R.Ford.” The fact that Woodsworth

thought it was appropriate to include Ford’s extremely bigoted slurs speaks

volumes about his own beliefs.

A decade later, in 1919, Ford was writing

antiRed diatribes for The Times, a Toronto daily. Historian

Michael Dupuis, in studying distorted news coverage of the Winnipeg General

Strike, said Ford’s stories prove that “fact was often replaced by half-truths

and false accusation.”43

Interestingly, Ford, who became an Ottawa

alderman and then the longtime editor of the London Free Press, fathered

Robert Ford, the Liberal government’s longstanding ambassador to the

USSR (1964-1980) and later, it’s Special Advisor on East-West Relations

(1980-1984).44

Woodsworth’s solutions to the immigration

“problem” included:

(1)

Further restricting the immigration of

non-white, non-English-speaking aliens,

(2)

Opening the gates to white Christians from the

UK, Germany and Scandinavia,

(3)

Implementing better church- and state-run

assimilation programs for nonAnglos who were already “within our gates,” and

(4)

Curtailing the civil and political rights, such

as the right to vote, of certain immigrants who could not be trusted.

Woodsworth chose a mixture of metaphors used by

eugenicists, militarists and empire loyalists to describe the most desirable

filters for selecting immigrants:

“We need more of our own blood to assist us

to maintain in

Canada

our British traditions and to mould the incoming armies of foreigners into loyal

British subjects.”45

Woodsworth’s choice of sources is instructive.

All thirteen of his recommended books, which he said “proved helpful” in writing

Strangers Within Our Gates, were by US authors. Most were of west

European heritage and from a highly-privileged class. The first seven books

promoted overtly racist stereotypes, praised eugenics, advocated Anglo-Saxon

superiority, pushed US imperialism, and/or saluted the work of Protestant

missionaries.46

Five years later, just after the outbreak of

WWI, Woodsworth addressed Winnipeg’s prestigious Canadian Club on “The Immigrant

Invasion after the War: Are We Ready for it?” This was one of 16 lectures in

1914 that were attended, on average, by 430 of the city’s most powerful men.

His talk came between speeches by Solicitor General Arthur Meighen on WWI, and

Prime Minister Borden on “Canada and the Empire.”

Other speakers that year included the top brass from Canada’s

ultraconservative military, banking and press establishments.47 The

fact that Woodsworth was warmly welcomed by this powerful circle, reveals his

role as the Canadian elite’s favourite “socialist.”

No longer leading Winnipeg’s Methodist Mission,

Woodsworth was then secretary of the Canadian Welfare League (1913-1916). The

self-described purpose of this national, Winnipeg-based organisation was to

confront “emergent social problems caused,” in part, by Canada’s “large and

heterogeneous immigration.”48

The Canadian Club introduced Woodsworth’s speech

by saying that

“the war had clearly revealed to us... [t]hat

we had in our midst large numbers of undigested aliens who might cause a serious

disturbance within our body politic.”49

This phraseology, plagiarised Charles Gordon’s

1908 novel which had warned of “an undigested foreign mass” in “the body

politic” that must be “absorbed...or it will be a mighty bad.”50

(When Woodsworth gave his 1914 speech to the Canadian Club, Gordon—who

had cofounded the club in 1904 and been its president, 1909-1910—was in Europe

building a new career as Canada’s leading military chaplain.)

“The danger now to be guarded against,”

began Woodsworth in his speech, “is that a sudden panic may lead us to take

extreme positions and thus intensify and perpetuate racial bitterness and

animosities.”51 Woodsworth

must have known that just four months earlier,

Canada

had taken an “extreme position” by interning thousands of civilians in 12

slave-labour camps. Manitoba had two internment facilities, with one in

downtown Winnipeg. Was this not “extreme” enough for Woodsworth?

Woodsworth then presented what he saw as

extremely disturbing set of statistics. In 1901, he said, 57% of

Canada’s 5.4 million inhabitants were British but of the 2.9 million that had

been admitted since then only 38% were British. Of those allowed in since 1901,

27% were non-English speakers. Of these, two thirds were from south and eastern

Europe. British immigration had decreased by 10% over the previous two years

and the percent of non-English newcomers was rising. After listing 24

non-English nationalities pouring into

Canada’s gates, Woodsworth asked:

“Mix these peoples together, and what is the

outcome? From the racial standpoint it is evident that we will not longer be

British, probably no longer Anglo-Saxon. From the standpoint of eugenics it

is not at all clear that the highest results are to be obtained through the

indiscriminate mixing of all sorts and conditions.... From the religious

standpoint, what will be the outcome? For...most of our foreign immigrants do

not belong to the churches which are... dominant in

Canada. From

the political standpoint it is evident that there will be very great changes and

very serious dangers.”52

(Emphasis added.)

Besides basing his rabid xenophobia on

ethnicity, politics and religion, Woodsworth’s racism was also tied to

“eugenics.” This phobic pseudo-science sought to improve humankind—physically,

culturally and morally—through selective breeding, sterilisation and

segregation. In 1916, Woodsworth was promoting eugenics through his work as

Director of the Bureau of Social Research (BSR). This government agency

“actively campaigned for the segregation and sterilization of defectives.”53

Although this arm of the Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba governments

was created to deal with “mental defectives,” Woodsworth expanded its scope to

target other so-called “community problems,” such as “Our Immigrants.”54

The immigrants that most worried Woodsworth, and

Canada’s prairie governments, were the Ukrainians. Woodsworth’s BSR report,

Ukrainian Rural Communities (1917), contained some of the usual slurs

against this ethnic group:

“[T]he immigrant is invariably laboring

under the hypertrophy of racial, social, religious and mental traditions brought

from the old country. This is only natural, but it does not facilitate social

evolution. His marked racial physiognomy, temperament, habits and customs

hinder him...from merging into the Canadian society....”55

This section of Woodsworth’s report,

although rife with assimilationist views, was not penned by an AngloProtestant.

The author chosen by Woodsworth was Ivan Petruschevich, editor of the

Canadian Ruthenian,56 the

official organ of

Canada’s

Ukrainian Catholic Church. Between 1911 and 1927, this paper was financed by

Canada’s Catholic Bishops who were “solidly behind the Ukrainian eparch” in

Canada, and supported its leader Bishop Nykyta Budka.57 (See

pp.41-42.)

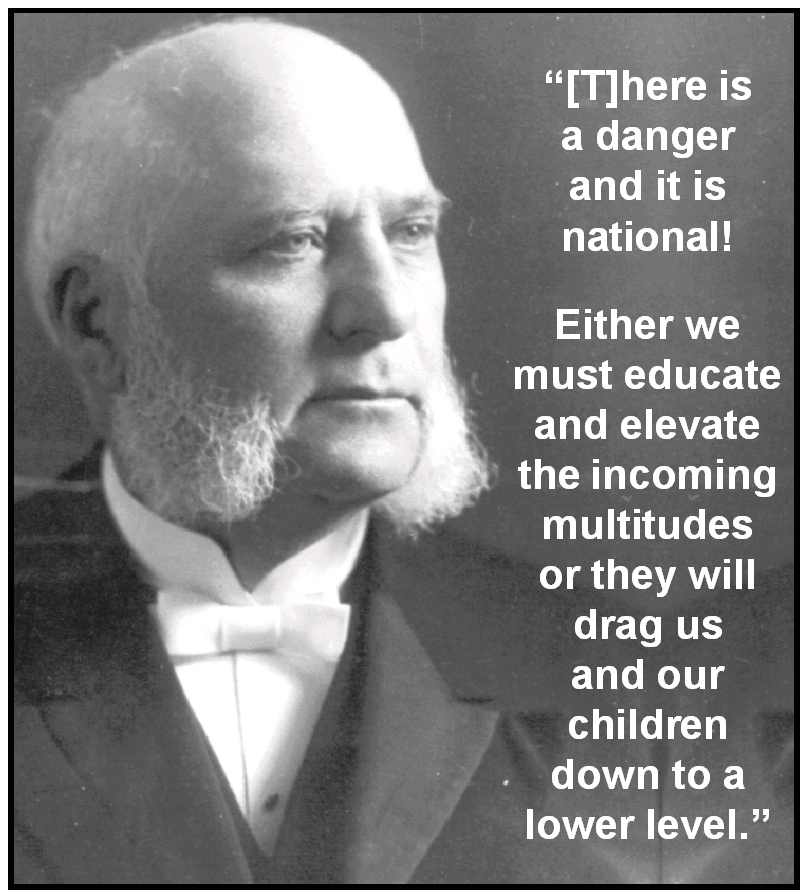

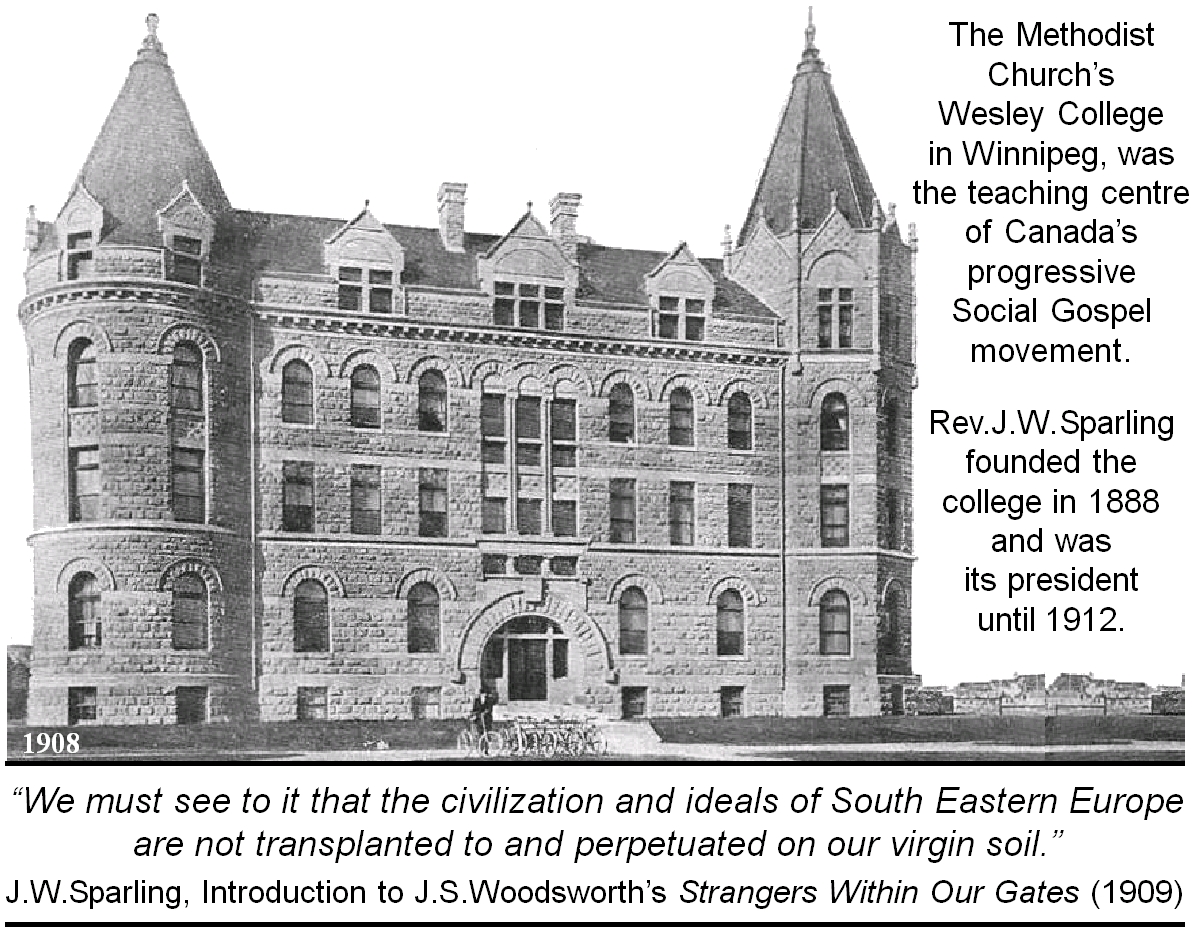

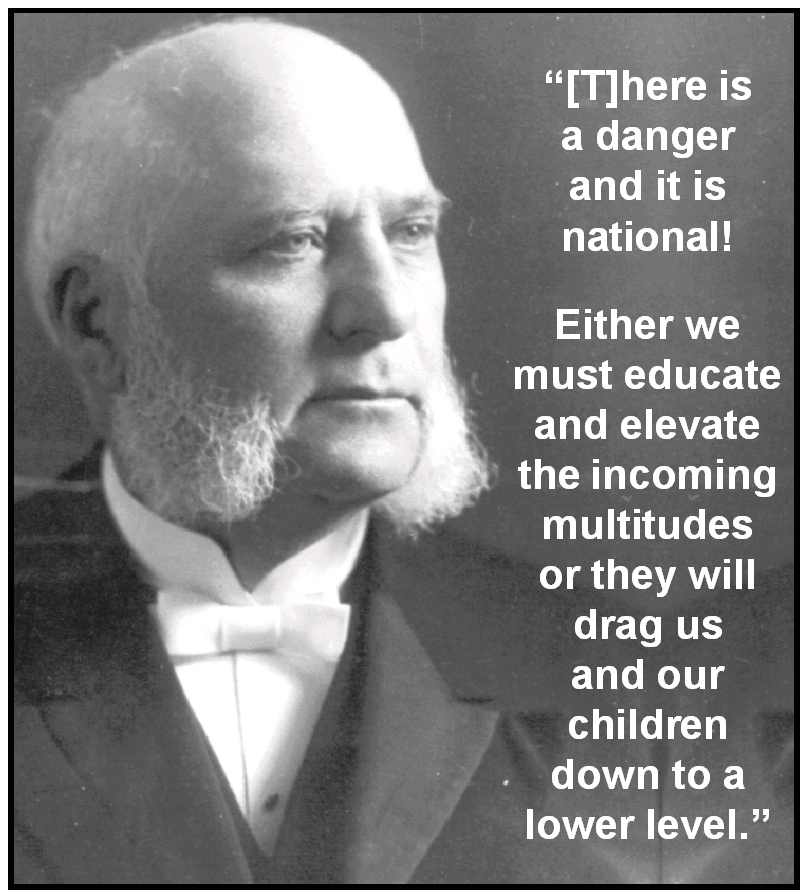

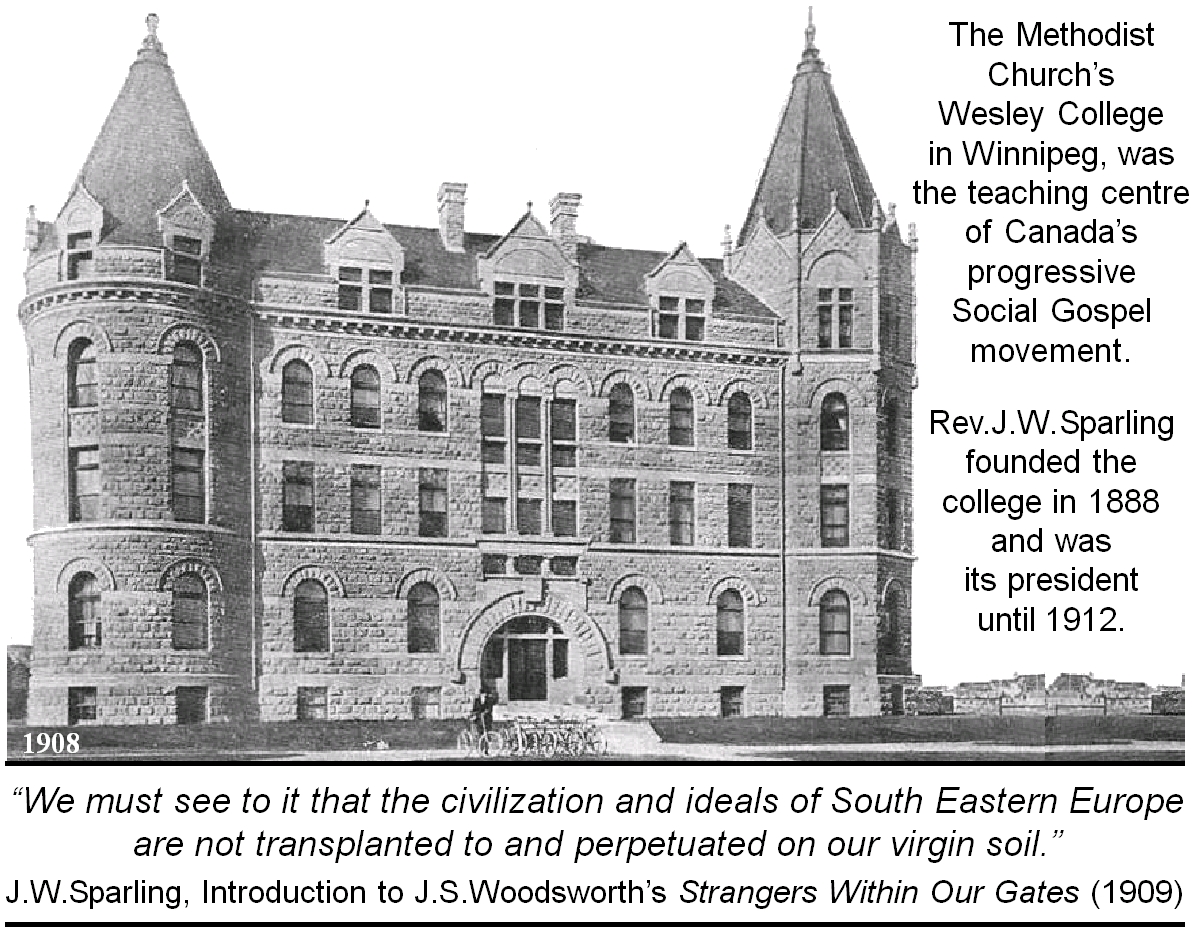

Rev. Joseph Sparling and Wesley College

Rev. Joseph Sparling and Wesley College

The introduction to Woodsworth’s Strangers

Within Our Gates was written by another prominent Social Gospeller, Rev.

Joseph W.Sparling. Like Woodsworth, Gordon, and The Foreigner’s hero,

Sparling was also a clergyman. Best known as the founder of Winnipeg’s Wesley

College, Sparling was its first principal from 1888 until his death in 1912.

This prestigious Methodist college, said Paul

Phillips, a historian at St. Francis

Xavier University, was

“established as a major training centre for Social Gospelers.”58

Richard Allen, a leading historian of Christian socialism, explained that “by

the first decade of the new century,” Wesley

College was, “if not the only, then the most vigorous source of the social

gospel in Canada.”59 Among

Wesley’s famous graduates was J.S.Woodsworth, who received its bronze metal in

“Mental and Moral Science” and was its “senior stick” (student president) when

he graduated in 1896.60

Wesley’s faculty included Canada’s pre-eminent

Social Gospel leader, Rev. Salem Bland, who Sparling recruited in 1903. Bland

taught at Wesley until 1917,61

when he was fired thanks to College chair and Winnipeg mayor, James

Ashdown, who saw him as a fundraising liability.

Sparling’s introduction to Strangers

Within Our Gates, is the entry point through which to understand its key

message. Calling

Winnipeg

“the storm centre” of

Canada’s

immigration “problem,” Sparling framed Woodsworth’s book by saying: “Perhaps the

largest and most important problem” is how “incoming tides of immigrants of

various nationalities and different degrees of civilization may be assimilated

and made worthy citizens.”62

In crying out his alarm, Sparling exclaimed:

“[T]here is a danger and it is national! Either we must educate and elevate the

incoming multitudes or they will drag us and our children down to a lower

level.” He made it clear which aliens posed the biggest threat to progress: “We

must see to it that the civilization and ideals of

South Eastern

Europe are not transplanted to and perpetuated on our virgin soil.”63

Sparling concluded his fearmongering, warning

knell about dangerous aliens by saying: “I fear that the Canadian churches have

not yet been seized of the magnitude and import of this ever-growing problem.”

Having the principal of Wesley College ring out religious alarm bells from the

ivory tower of Canada’s Social Gospel movement was like shouting “Reds!” in a

crowded church.

But Sparling was not all doom and gloom. His

panicstricken entrée to Woodsworth’s textbook urged “all our young people” to

“read and ponder” its subject matter. “I can with confidence commend this

pioneer Canadian work,” said Sparling, “to the careful consideration of those

who are desirous of understanding and grappling with this great national

danger.”64

But Sparling was not all doom and gloom. His

panicstricken entrée to Woodsworth’s textbook urged “all our young people” to

“read and ponder” its subject matter. “I can with confidence commend this

pioneer Canadian work,” said Sparling, “to the careful consideration of those

who are desirous of understanding and grappling with this great national

danger.”64

In his otherwise darkly ominous and

foreboding opening to Woodsworth’s primer, Sparling saw only one other

positive light at the end of the tunnel. That light was a wealthy capitalist and

Winnipeg’s

then-Mayor, J.H.Ashdown. (Ironically, five years after Sparling’s death, Ashdown

was responsible for firing Wesley’s most famed Social Gospeller, Salem Bland.)

In what reads like a paid political ad, Sparling praised Mayor Ashdown for

believing that the problem of assimilating foreigners was “vital and

fundamental.” He also lauded Ashdown as a “resident [of] the West for over

forty years” who had “perhaps given more time, attention, and money to the

working out of a solution of this question than any other layman in the West.”65

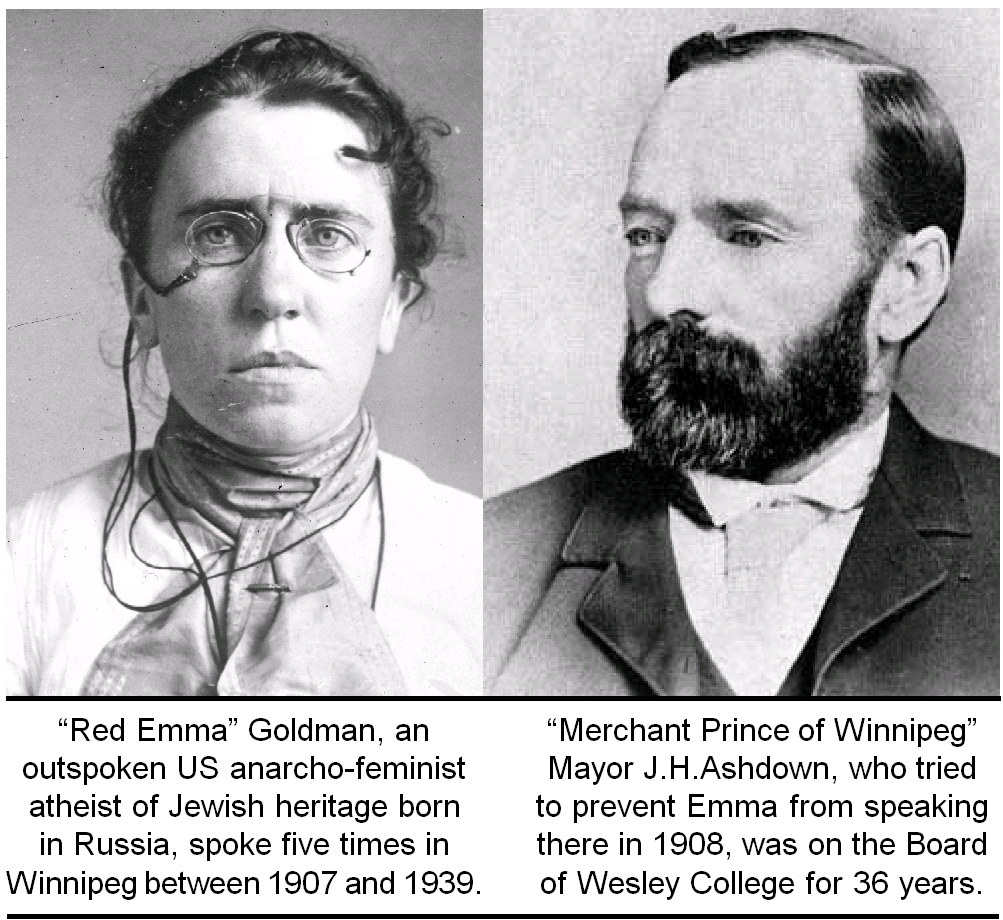

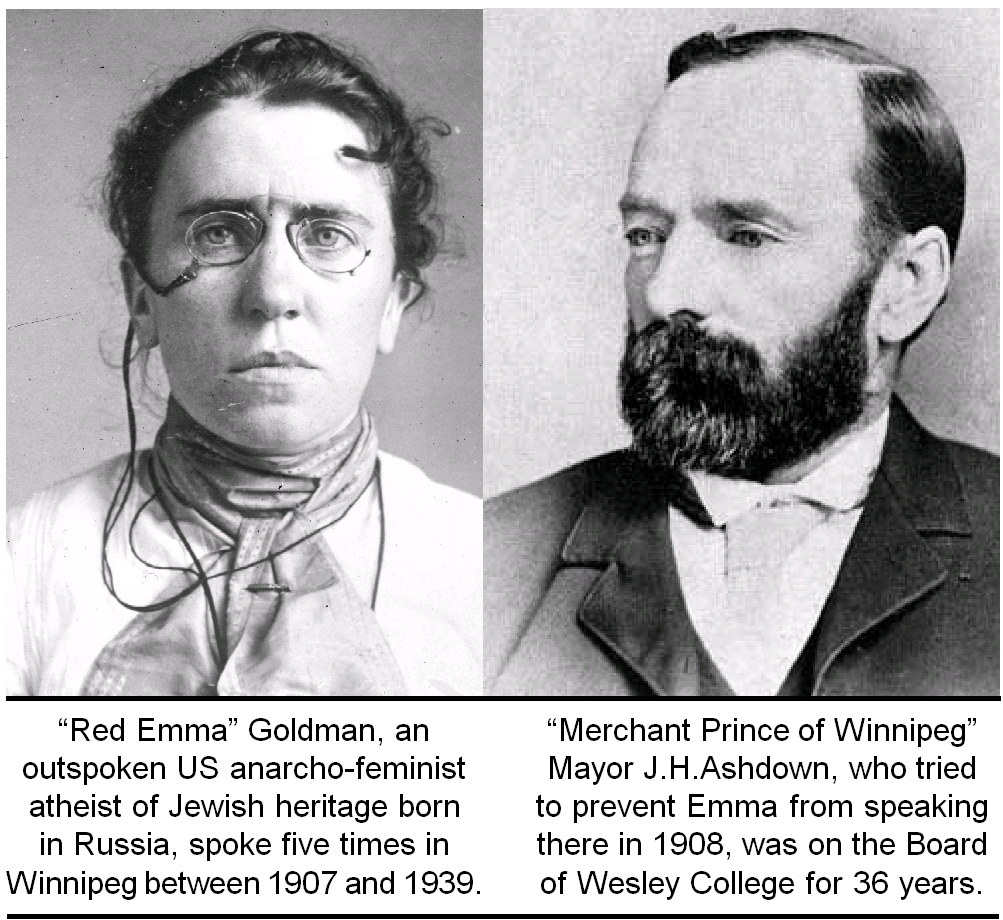

Although Sparling did not describe Ashdown’s

“solution” to the immigration problem, he must have known that the millionaire

mayor was rabidly averse to political radicals. This was public knowledge.

Ashdown’s “solution” included barring outspoken undesirables. In April 1908,

just two months before Woodsworth wrote the preface to his book, Ashdown—the

acclaimed “Merchant Prince of

Winnipeg”—tried to stop “Red Emma” Goldman from speaking in their city. Born to

a Jewish family in Russia, Goldman was a prolific

US

writer, lecturer and activist. She was also a philosopher, feminist, anarchist,

unionist, atheist and an advocate for peace, civil rights, free speech and birth

control.

Goldman had already visited

Winnipeg

twice. Her 1907 lectures included “The Curse of Religion” and “Trades Unionism

and the General Strike.”66 Wanting

to abort a repeat performance, Ashdown wrote to Liberal Interior Minister Frank

Oliver. (See below.) Ashdown explained:

“we have a very large foreign population in

this City, it consists approximately of 15,000 Galicians, 11,000 Germans, 10,000

Jews, 2,000 Hungarians and 5,000 Russians and other Slavs and Bohemians.

Many...have had trouble in their own country with their Governments and come to

the new land to get away from it but have all the undesirable elements in their

character that created the trouble for them before. They are just the right

crowd for Emma Goldman or persons of her character to sow seeds which are bound

to cause most undesirable growths in the future.”67

Some

Winnipeg

“NGOs” agreed. The Christian Women’s Temperance Union for instance, was fearful

that Goldman would further radicalise immigrants.

The Interior Ministry also tried to stop the

so-called “Apostle of Anarchy,” and her kind, from entering

Canada’s

gates. A 1908 memo to Minister Oliver from Superintendent of Immigration

W.D.Scott, said Ashdown’s letter had asked “whether the law could not be amended

in such a way as to keep such persons out.” Scott then suggested they “debar her

on the ground of insanity.”

Oliver however replied: “I am afraid that this is not sufficient warrant.”

Goldman’s lectures in late 1908 attracted over 1,500 Winnipeggers.68

Allowing US anarchists, like Goldman, to

enter

Canada’s

gates was also deplored by Boer-War veteran, Sir Sam Hughes. This bigoted

imperialist, Methodist and Conservative MP (1892-1921) was the WWI Minister of

Militia and Defence (1911-1916). “I would prefer a Hindu who has served the

Empire in the armies of

Great Britain,”

he said in July 1908, to a “Yankee who has been an anarchist ....[and] crosses

over to Canada, ...to disrupt the established laws.” Calling anarchists “a

class of animals,” he said many were “not worthy the name of human beings.”69

Although the government did not ban the entry of anarchists until 1910,

many were deported using such pretexts as poverty.

Besides their deeply shared aversion to

certain aliens, Sparling and Ashdown were both central to the

Methodist

Church’s Wesley College, Canada’s Social Gospel training centre. As its

founding president, Sparling had known Ashdown from Wesley’s board of directors

since its creation in 1888. Ashdown was the College’s bursar (1888-1890),

vice-chairman (1890-1908) and chair (1908-1924).70

Interestingly, during the Winnipeg General

Strike of 1919, said Norman Penner, “Ashdown’s hardware store... supplied

‘thousands’ of wagon spokes for clubs for the specials.”71 (The

“specials” were an 1,800-man force of ruthless, paramilitary thugs hired by the

city to attack strikers and protesters.) Later that year, Ashdown represented

western Canadian wholesalers at the government’s National Industrial Conference

in Ottawa.

It brought together handpicked government-friendly representatives from large

corporations, virulently antiCommunist labour unions and other captive,

civil-society organisations.

Culpability: Stirring the Pot

It is worth chewing on Gordon’s trope that

east Europeans were “an undigested foreign mass” to “be digested and absorbed

into the body politic.” In the Social Gospel’s heyday (1880-1920),

Canada’s

national dish was a banal daily fare of ethnocentric pottage that was as bland

and tasteless as it was racist. Spices were considered foreign and indigestible.

The garlic of east European cookery was particularly unpalatable, and communists

were the Red-hot chili peppers of politics, likely to provoke a revolting

upheaval from within.

When

Ottawa chefs

added so many immigrants to the prairie’s simmering nativist pot, the result was

a profound social dyspepsia. In their frenzy to dissolve these new ingredients

into the Canadian stock, AngloProtestants stirred the cultural stew into a

hateful froth of social frenzy. The mass phobia of mainstream culture saw east

Europeans as distasteful rabble-rousers who, unless contained and absorbed,

would spoil the tastefully civilised purity of Canada’s “Christian values.”

It was no wonder then that when the draconian

War Measures Act of 1914 passed unanimously through Parliament, thousands of

east Europeans were either deported without trial or sent into internal exile as

slaves in Canada’s remote gulag of WWI “concentration camps.” This huge

injustice occurred without any noticeable protest from AngloProtestant society.

Social Gospel leaders were not about to

protest WWI internment. They had long been among

Canada’s most

outspoken xenophobes, conjuring up fearmongeringly-hateful stereotypes of east

Europeans. Woodsworth, Gordon, Sparling and other leading Social Gospel

progressives, had long been ringing loud bells of warning to frame these

unwanted aliens as a special threat to Canada. When WWI provided the pretext to

remove “enemy aliens” from Canadian society, many Social Gospellers likely saw

this as a religious, economic and political godsend, not an injustice.

Similarly, the churches were not only key supporters of the genocidal program to

concentrate Aboriginals on reserves, they worked as faithful agents of the state

to administer residential schools.

Canadian chauvinism became a national

prisonhouse—if not a mental asylum—whose inmates were truly committed to their

national cult. Although trapped by the seductive allure of elitist

AngloProtestant institutions, and shackled by their collective narcissism,

prisoners of the Canada Syndrome were committed to spreading the mass delusion

that they were free. Dedicating themselves to building the very institutions and

narratives that had metaphorically captured them, those faithful to the

official myth of Canadian exceptionalism were duty bound to accept if not run

national programs that literally imprisoned the enemies of both church

and state.

Social Gospellers not only reflected the

religious and political bigotries that panicked Canada’s civil society, they

were influential social gatekeepers whose narratives greatly influenced

the mass psychosis of fear and loathing that spread throughout the

AngloProtestant mainstream.

By selecting, filtering and interpreting stories

about unwanted “strangers,” from a variety of intolerant sources, Social Gospel

gatekeepers created convincing narratives to rationalise, promote, shape and

prolong the chauvinism that dominated Canadian society. By shepherding

mainstream suspicions of foreigners into a virulent xenophobia, Canada’s Social

Gospellers went far beyond serving as wardens and guardians fixated on watching

the nation’s gates. These well-meaning, progressives became hardened cultural

warriors whose powerfully eloquent narratives aided and abetted the mass

physical captivity of aliens, as well as the ideological captivity of the

Peaceable Kingdom’s dominant AngloProtestant society.

http://books.google.ca/books?id=R1gsAAAAMAAJ

This

article was written for and first published in

This

article was written for and first published in But gates are not just entry points, they

are also exits for expelling the unwanted. While between 1903 and 1908

But gates are not just entry points, they

are also exits for expelling the unwanted. While between 1903 and 1908  Using the alias Ralph Connor, Gordon was “the

most successful practitioner …in the world” of a genre called “imperial

adventure fiction.”

Using the alias Ralph Connor, Gordon was “the

most successful practitioner …in the world” of a genre called “imperial

adventure fiction.” Many who still revere Woodsworth have no

idea that before WWI, he led the way in fearmongering attacks against unwanted

foreigners. In 1909, one year after Charles Gordon’s novel, The Foreigner,

Woodsworth released an utterly racist tome called Strangers Within Our

Gates. Published by the

Many who still revere Woodsworth have no

idea that before WWI, he led the way in fearmongering attacks against unwanted

foreigners. In 1909, one year after Charles Gordon’s novel, The Foreigner,

Woodsworth released an utterly racist tome called Strangers Within Our

Gates. Published by the  Woodsworth’s section on Ukrainians was penned by

journalist Arthur R. Ford of the Winnipeg Telegram. Ford, the son of

Methodist Minister James Ford, described “how difficult the problem of

Canadianizing” them could be. Warning that Ukrainians were “crowding to our

shores,” he revealed “the cold fact” that 125,000 had already arrived, and that

40,000 were within Manitoba’s gates. He then remarked that Canadians had “so

low an estimation” of them “that the word Galician is almost a term of

reproach.” He also associated Ukrainians with violence and criminality by

saying that their

Woodsworth’s section on Ukrainians was penned by

journalist Arthur R. Ford of the Winnipeg Telegram. Ford, the son of

Methodist Minister James Ford, described “how difficult the problem of

Canadianizing” them could be. Warning that Ukrainians were “crowding to our

shores,” he revealed “the cold fact” that 125,000 had already arrived, and that

40,000 were within Manitoba’s gates. He then remarked that Canadians had “so

low an estimation” of them “that the word Galician is almost a term of

reproach.” He also associated Ukrainians with violence and criminality by

saying that their

But Sparling was not all doom and gloom. His

panicstricken entrée to Woodsworth’s textbook urged “all our young people” to

“read and ponder” its subject matter. “I can with confidence commend this

pioneer Canadian work,” said Sparling, “to the careful consideration of those

who are desirous of understanding and grappling with this great national

danger.”

But Sparling was not all doom and gloom. His

panicstricken entrée to Woodsworth’s textbook urged “all our young people” to

“read and ponder” its subject matter. “I can with confidence commend this

pioneer Canadian work,” said Sparling, “to the careful consideration of those

who are desirous of understanding and grappling with this great national

danger.”