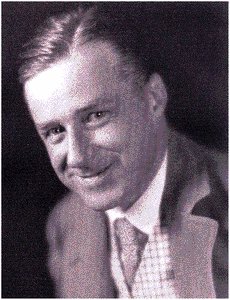

George M. Moffett

By Richard Sanders, Editor, Press for Conversion!

Moffett is known to have donated at least $10,000 to

American

Liberty League and $7,500 to one of its front groups, the

Crusaders.

As president of the Corn Products Refining Co. (CPRC), Moffett

presided over some of the country’s most advanced, chemistry

labs. CPRC processes made pure starch, for corn “syrup,”

and had invented Mazola oil in 1910. Corn is more than just a

food, it’s also a source of raw power, metaphorically and

literally. In 1906, the leading U.S. corn refiners merged into

one huge company, with capital of $33 million. It was organized

by Edward Bedford, of Thompson & Bedford Co., a marketing

firm for Rockefeller’s

Standard Oil lubricants. Bedford, a Standard Oil director since

1903, also had a brother and cousin on the board. By 1912, CPRC

was one of the world’s largest company. In 1916, Judge Learned

Hand ruled against the edible oil, “Glucose Trust.”

During that suit, a memo was exposed in which the CPRC president

said, “We have built a Chinese Wall around our competitors

and have them in chains.” (For decades, CPRC fought antitrust

actions and continued its predatory practices.) By 1919, CPRC

controlled Canada Starch and the plot thickened. In the 1920s

and 1930s, CPRC’s alcohol distilleries were linked to the

mafia’s National Crime Syndicate, that was bootlegging liquor.

In those years, CPRC was among fewer than two dozen companies

that dominated U.S. investments in Germany. When Germany’s

Knorr Co. needed infusions of cash starting in 1922, the CPRC’s

German subsidiary got loans from the U.S. head office. By 1958,

CPRC owned Knorr completely.

In a joint venture with Texaco called Pekin Energy, CPRC uses

corn starch to make millions of gallons of Ethanol per year. The

history of this fuel is instructive. When Germany’s oil supplies

were threatened in 1915, they switched to ethyl, thus prolonging

WWI. In the 1920s, Henry Ford, author of The International Jew:

Jewish Influences in American Life, one of Hitler’s greatest

fans and financiers and president of the Ford Motor Co., called

ethyl the “fuel of the future.” By the 1930s, there

was much research into the fuel. Ethyl-gas use was growing, especially

in Europe, but the major oil firms squashed it by acquiring control

over industrial alcohol production. Between 1913 and the 1930s,

the U.S. government’s anti-trust committees looked into this

sinister connection. Investigations into Standard Oil’s links

to I.G. Farben, in the early 1940s revealed that du Pont, a top

oil behemoth, owned large U.S. and Cuban distilling firms. As

mentioned above, a Standard Oil director/marketer was instrumental

in the formation of CPRC. Just before WWII, the U.S. dropped its

antitrust cases. However, top oil industry directors did have

to resign and oil firms’ supposedly sold off their alcohol

distillery stocks.

Vast investments in Germany, and the financing of fascist groups

in the U.S., were not obstacles to Moffett’s involvement

in government war planning. In 1940, Roosevelt appointed Moffett

to the Council of National Defense, which oversaw industrial production.

GM executive and Nazi admirer, William

Knudsen, oversaw the government’s National Defense Advisory

Commission. He had senior officials from large industries advising

on construction, machine tools, heavy ordnance, aircraft, shipbuilding,

small arms and ammunition. Advising on chemicals was George Moffett,

for the CPRC.

In 1942, the U.S. government seized American assets of I.G.

Farben, the Nazi’s top chemical/munitions cartel, namely,

General Aniline & Film (GAF), General Dyestuffs, its 50% holding

in Winthrop Chemical and its Jasco stock (in trust for Standard

Oil, NJ). The U.S. Alien Property Custodian imposed new managers

on these Nazi-linked companies, but the Justice Department’s

Antitrust Division (AD) objected to the managers chosen. One was

a U.S. oil firm official. An AD official said: “the connection

between I.G. Farben and all oil concerns here is well-known.”

Despite having major chemical subsidiaries and investments in

Germany, another new manager came from CPRC. The AD said: “It

can be assumed that [CPRC’s German] subsidiaries... are connected

by cartel agreements with other German chemical works, especially

I.G. Farben.” In the early 1930s, CPRC and GAF were linked

through Gibson Island Research Conferences, which brought together

top U.S. corporate chemists on a secluded island. Other American

Liberty League-linked chemical firms, also networked at these

intimate getaways: du

Pont, Firestone, H.J.Heinz,

Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Standard Oil and Sun

Oil.

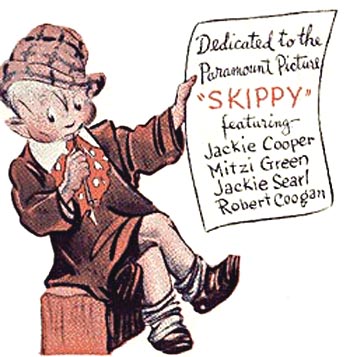

Perhaps

the saddest chapter in CPRC’s litany of scandals was its

role in stealing Skippy, a popular comic strip that hit the papers

in the early 1920s. It’s maverick creator, Percy Crosby,

knew General

Smedley Butler and shared his convictions. Crosby used his

cartoon character to tackle politicians, corporate criminals,

Al Capone’s mafia and the KKK. Skippy ran worldwide from

1926 to 1945 and championed civil rights, child labour laws and

free speech. Crosby became a wealthy man but was obviously a threat

to the upscale fascist, corporate elite and seamy underworld gangsters.

Then, in 1933, along came a bankrupt company, Rosefield Packing.

It stole the good Skippy name, its lettering and distinctive graphics

and used them to sell peanut butter. They even had a “Skippy”

radio show, 1933-1935. It was sponsored by an I.G. Farben subsidiary,

Sterling Products Co., and a CPRC official was on the Sterling

Drug Co. board.

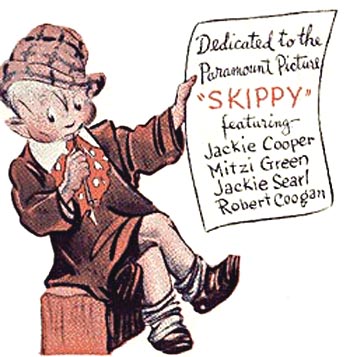

Perhaps

the saddest chapter in CPRC’s litany of scandals was its

role in stealing Skippy, a popular comic strip that hit the papers

in the early 1920s. It’s maverick creator, Percy Crosby,

knew General

Smedley Butler and shared his convictions. Crosby used his

cartoon character to tackle politicians, corporate criminals,

Al Capone’s mafia and the KKK. Skippy ran worldwide from

1926 to 1945 and championed civil rights, child labour laws and

free speech. Crosby became a wealthy man but was obviously a threat

to the upscale fascist, corporate elite and seamy underworld gangsters.

Then, in 1933, along came a bankrupt company, Rosefield Packing.

It stole the good Skippy name, its lettering and distinctive graphics

and used them to sell peanut butter. They even had a “Skippy”

radio show, 1933-1935. It was sponsored by an I.G. Farben subsidiary,

Sterling Products Co., and a CPRC official was on the Sterling

Drug Co. board.

The CPRC sugared up “Skippy” peanut butter and later

purchased Rosefield. Crosby had to fight a David-and-Goliath-style

legal battle against CPRC. It turns out that Crosby’s lawyer,

Herbert Brownell, also worked for the CPRC! Brownell later became

Attorney General for Eisehower and Nixon. Crosby’s daughter,

Joan, notes that

"’Wild Bill’ Donovan, former head of the [Office

of Strategic Services, the CIA’s forerunner], was one of

my father’s former lawyers. Allen Dulles and [brother] John

Foster [were lawyers] with the Sullivan & Cromwell law firm

(which was lead counsel for Best Foods in 1954 when it ‘bought’

Skippy assets from Rosefield Packing)."

In 1958, CPRC and Best Foods merged to form CPC. The McCarthy-era

legal battle over Skippy devastated Crosby. He was forced into

a psychiatric institution for 16 years until his death in 1964.

His efforts to contact family, friends and authorities were thwarted.

Crosby’s daughter says he

"was a political prisoner of the powerful Corn Products

Corp., which had stolen his Skippy business, destroyed his reputation

and career, and looted his estate of valuable assets. My father

was held hostage by this evil combination, and died in virtual

poverty, while CPC made millions of dollars from the Skippy criminal

enterprise."

CPC has tried to ban her website <www.skippy-scam.org>.

In 1996, CPRC paid $7 million to settle a lawsuit for corn

syrup price fixing. In 2003, it was revealed that the International

Life Sciences Institute, an international “food” industry

association, had infiltrated the World Health Organisation to

exert “undue influence” over policies on diet, pesticides,

additives, transfatty acids, sugar and genetically modified foods.

It was founded in 1978 by the Heinz Foundation. Among its top

members are CPC International and Knorr. With sales of $2.3 billion

in 2003, CPC is the world’s top dextrose producer and one

of America’s top 30 industrial stocks. It has 115 plants

in 60 countries and employs 50,000. Since Unilever bought Bestfoods

in 2000, CPRC is now part of that corporate conglomerate.

References:

Richard Tedlow, "The American CEO in the 20th Century,"

2003.

http://www.hbs.edu/research/facpubs/workingpapers/papers2/0203/03-097.pdf

Corn Products Company

http://www.scripophily.net/corprodcom.html

Education

http://www.ubfoods.co.uk/education_content_knorr.htm

Bill Kovarik, "Henry Ford, Charles Kettering and the Fuel

of the Future," Automotive History Review, Spring 1998.

http://www.radford.edu/~wkovarik/papers/fuel.html

Mark Glick, Duncan Cameron, David Mangum, "Importing the

Merger Guidelines," 1997.

http://www.econ.utah.edu/les/version_2.0/papers/importing.html

Alan Gropman, "Mobilizing U.S. Industry in World War II,"

McNair Paper, 1996.

http://www.ndu.edu/inss/McNair/mcnair50/m50c5.html

Wyatt Wells, Antitrust and the Formation of the Postwar World,

2003.

http://www.ciaonet.org/book/wew01/

Russell Mokhiber & Robert Weissman, "The Surprising

Political Economy of Skippy," July 30, 1999.

http://lists.essential.org/corp-focus/msg00033.html

Joan Crosby, "Percy L. Crosby: His Life and Times,"

July 16, 1999.

http://www.skippy-scam.org/exhibit-B-1/skippy11.html

Joan Crosby, personal communication with author, February,

2004

Wall Street Journal, 5/28/1996, p. R-45, cited in Timelines

of History.

http://timelines.ws/20thcent/1958.HTML

Backgrounder

http://www.cornproducts.com/PressKit.pdf

Bestfoods

http://www1.excite.com/home/careers/company_profile/0,15623,1306,00.html

"Achtung!! September Blues," World Market Chronicles,

Oct. 2002.

http://www.depression2.tv/chronicles/september-blues.html

Sarah Boseley, "WHO 'infiltrated by food industry,"

The Guardian, Jan. 9, 2003.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,871228,00.html

Source: Press for Conversion!

magazine, Issue # 53, "Facing the Corporate Roots of American

Fascism," March 2004. Published by the Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade.

Order a Copy: Order

a hard copy of this 54-page issue of Press for Conversion!

on the fascist plot to overthrow President F.D.Roosevelt and

the corporate leaders who planned and financed this failed coup.

Perhaps

the saddest chapter in CPRC’s litany of scandals was its

role in stealing Skippy, a popular comic strip that hit the papers

in the early 1920s. It’s maverick creator, Percy Crosby,

knew General

Smedley Butler and shared his convictions. Crosby used his

cartoon character to tackle politicians, corporate criminals,

Al Capone’s mafia and the KKK. Skippy ran worldwide from

1926 to 1945 and championed civil rights, child labour laws and

free speech. Crosby became a wealthy man but was obviously a threat

to the upscale fascist, corporate elite and seamy underworld gangsters.

Then, in 1933, along came a bankrupt company, Rosefield Packing.

It stole the good Skippy name, its lettering and distinctive graphics

and used them to sell peanut butter. They even had a “Skippy”

radio show, 1933-1935. It was sponsored by an I.G. Farben subsidiary,

Sterling Products Co., and a CPRC official was on the Sterling

Drug Co. board.

Perhaps

the saddest chapter in CPRC’s litany of scandals was its

role in stealing Skippy, a popular comic strip that hit the papers

in the early 1920s. It’s maverick creator, Percy Crosby,

knew General

Smedley Butler and shared his convictions. Crosby used his

cartoon character to tackle politicians, corporate criminals,

Al Capone’s mafia and the KKK. Skippy ran worldwide from

1926 to 1945 and championed civil rights, child labour laws and

free speech. Crosby became a wealthy man but was obviously a threat

to the upscale fascist, corporate elite and seamy underworld gangsters.

Then, in 1933, along came a bankrupt company, Rosefield Packing.

It stole the good Skippy name, its lettering and distinctive graphics

and used them to sell peanut butter. They even had a “Skippy”

radio show, 1933-1935. It was sponsored by an I.G. Farben subsidiary,

Sterling Products Co., and a CPRC official was on the Sterling

Drug Co. board.