Fictive Canada:

Issue #69,

Press for Conversion! (Fall 2017)

Click here for info about

symbolism of the front cover collage |

|

|

Table of Contents 1-

True Crime Stories and

2-

John Cabot & Britain’s Fictitious Claim on

Canada: > Why “The Dominion of Canada”?

3-

Canada’s Extraordinary Redactions:

4-

Textbook Cases of Canadian Racism:

5-

From Popes and Pirates to Politicians and

Pioneers: >

The Canadian Legal Fiction of

6-

Breaking the Bonds of Ignorance and Denial:

>

Oh say can you see? Blindsport

for Peaceable Racism

7-

Native

Captivity and Slave Labour 8-

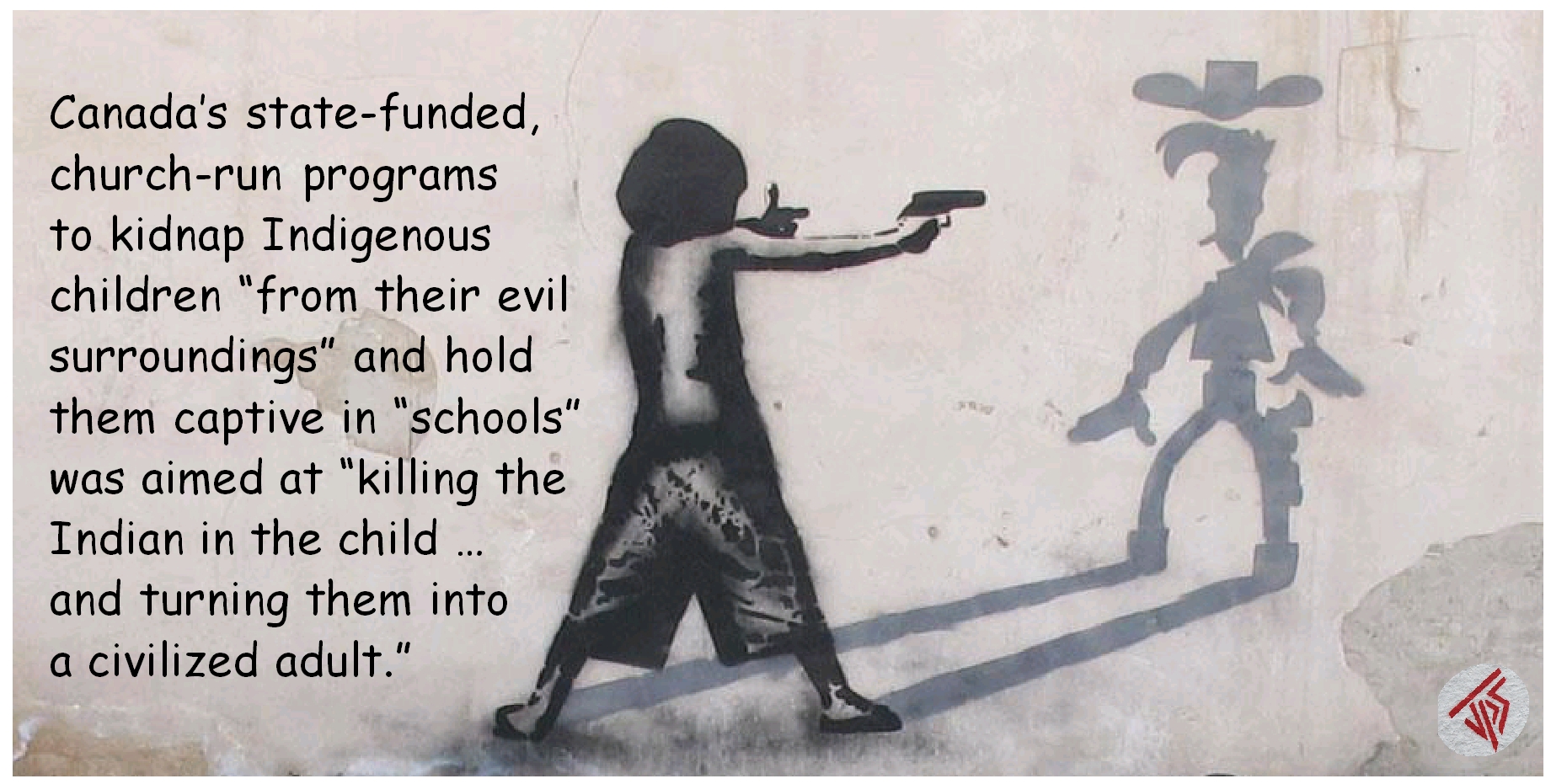

Child Slavery in Canada’s

>

Jean L’Heureux:

|

Textbook Cases of Canadian Racism: Canadian History Books as

View this article from

Fictive Canada (pp.15-18) in PDF format History textbooks are not found in the fiction section of the library. Many should be. The artificial divide between works of fiction and nonfiction is well illustrated by the false narratives about Indigenous people found in Canadian school books. These texts have been key to promoting patriotism and faith in the nation-building project called ‘Canada.’ Achieving this goal has usually been far more important than conveying disturbing truths about the unjust treatment of First Nations by Europeans. A good example of what anthropologist Bruce Trigger called the "nationalistic history-writing of the post-Confederation era" can be found in the disturbingly infantile, but still-quoted textbooks of Henry H. Miles. He penned such widely read tomes as The Child’s History of Canada (1870), A School History of Canada (1870) and The History of Canada under French Régime, 1535–1763 (1872). These texts for elementary and middle schools venerated the supposed European heroes who "discovered" Canada. Describing Jacques Cartier as "a noble specimen of a mariner," Miles began his 1872 history text with this sycophantic drivel: Canada was discovered in the year 1534, by Jacques Cartier … a man in whom were combined the qualities of prudence, industry, skill, perseverance, courage, and a deep sense of religion.1 Miles’ naive, hero-worshipping view of Cartier reflected his efforts to reconcile English and French Canadian histories.2 In contrast to this conciliatory approach, Miles exhibited the virulent, officially sanctioned racism towards First Nations shared by most French- and English-speaking Canadians. One Miles’ text informed Canadian children, both Protestant and Catholic, that the "Indians … of Canada and New England were all savages and heathens." He also stated that "the ferocious instincts of ... the Indian tribes" were harnessed by the French and English in their 17th-century colonial wars.3 Hundreds of times, Miles called Indigenous people either "barbarians" or "savages." Stating that all Indians were "believers in witchcraft," Miles cited a prominent Catholic historian, John G. Shea, who demonised native people by saying: "Pure unmixed devil-worship prevailed throughout the length and breadth of the land."4 |

|

Miles presents a sanitised account of the litany of injustices committed by Europeans against Indigenous peoples. This is exemplified in his rendition of how Cartier kidnapped two youths — the sons of Chief Donnacona of Stadacona, near present-day Quebec City — during his first voyage in 1534. The mariner’s account of the event leaves no doubt what happened. Cartier’s journal refers to the victims as "prisoners" and uses the words "seized," "captured" and "detained" to describe their forced abduction. (For more on Cartier’s version of the event, see pp.12-13). Miles however, omits these references to captivity, saying that Donnacona and sons were "easily induced ... to pass into the ship." After seizing them, "Cartier made known to the chief his wish to take two of his sons away with him for a time. The chief and his sons," said Miles, "appear to have readily assented."6 Miles conceded that some authors "strongly condemned Cartier as having practised cruelty and treachery on this occasion ..." but claimed, "the facts here recorded disprove the accusation."7 Miles justified Cartier’s method "to obtain possession of two of their young men," by saying the mariner’s noble intention, to "train them as interpreters" and "instruct them in religion and the habits of civilized life, places his conduct in very favourable light."8 Miles also explained away the kidnapping of Stadaconan chiefs during Cartier’s second voyage (1535-1536) using the "favourable light" of civilising and Christianising Indians: Cartier’s expectation was that their abduction could not but result in their own benefit, by leading to their instruction in civilisation and Christianity, and that it might be afterwards instrumental in producing the rapid conversion of large numbers of their people.… [C]onsidering the inherent viciousness of the Indian character, Cartier’s intercourse with the Indians was conducted with dignity and benevolence .…9 Miles’ widely read and often-reprinted school books served the Crown. They helped indoctrinate generations of Canadians to accept the genocide that had been taking place since Europeans landed in what is now Canada. All of Miles’ racist texts were published by Dawson Brothers of Montreal,10 a firm led by Samuel Dawson, who became "Printer to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty." Dawson’s appointment as Canada’s official printer gave him a deputy minister rank and put him in charge of Canada’s voters’ lists, the printing and distribution of all public documents, and the auditing of all government advertising.11 Dawson received this patronage "partly for his services to the government."12

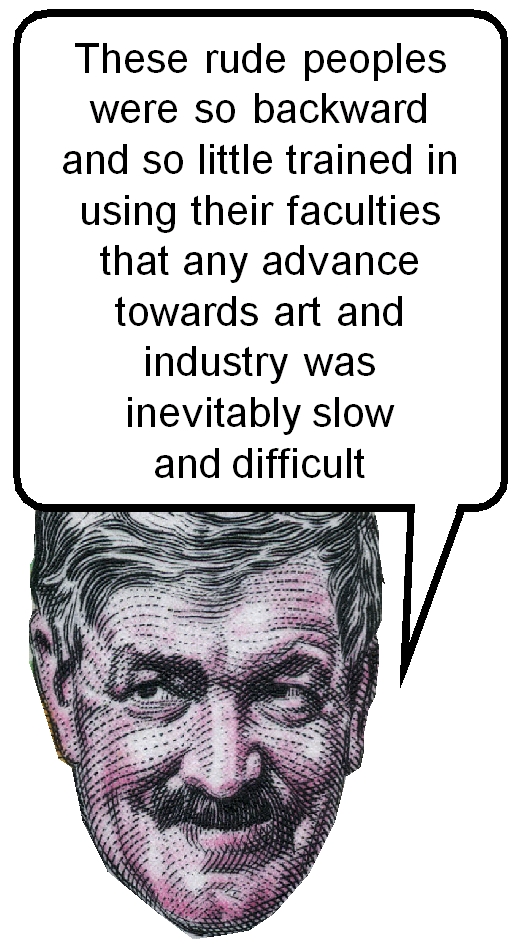

One might expect that such racist texts could find no place in today’s accounts of Cartier. However, even in this age of multicultural "Canadian values," Miles’ varnished tales live on. In fact, his sugar-coated history is featured as the primary article on Cartier by an internet source that calls itself "the #1 web site in the world about Canadian history, heritage and culture."15 This site, Canada history.com, includes the three chapters on Cartier from Miles’ History of Canada under the French Regime.16 This widely read, online resource reprints Miles’ entire 1872 narrative, word-for-word, without any context, analysis or critique of his perverted views. Miles’ gilded rendition of Cartier as a great hero appears on this website without the book’s name, or publication date, let alone any denunciation of Miles’ narrative as Canadian hate literature that was formerly used in many schools. Sadly, Miles was only one in a long line of Canadian historians who targeted Indigenous peoples with racist fictions. Another example is Stephen Leacock. Best known for his satirical stories about small-town Ontario, he was, says The Canadian Encyclopedia, "the English-speaking world’s best-known humorist" between 1915 and 1925. Few now know that Leacock was a professor of political economy at the University of McGill (1903-1936).17 Armed with a PhD in economics and political science, he wrote several Canadian history texts. His efforts at nonfiction might also be seen as humour if they were not so riddled with degrading stereotypes of Indigenous peoples. Among Leacock’s worst stabs at nonfiction were three volumes of The Chronicles of Canada. This 32-volume encyclopedia was edited by the aptly-named G.M. Wrong, an Anglican priest, University of Toronto history professor and department head (1894-1927) and influential founder of the Canadian Historical Review,18 which is still billed as the premiere journal of Canadian history. In The Chronicle’s first volume, The Dawn of Canadian History, Leacock gave a very dry account of how white people brought civilisation to the wild and depraved savages of Canada. He declared that Indigenous peoples were vastly inferior to Europeans, who represented the pinnacle of global civilization. He instructs us, for example, that "the Indians of Canada had not emerged even from savagery to that stage half way to civilization which is called barbarism." Leacock’s racist rants about those he typecast as ignorant "savages" knew few bounds. "When the white men first came these rude peoples were so backward and so little trained in using their faculties," he proclaimed, "that any advance towards art and industry was inevitably slow and difficult."19

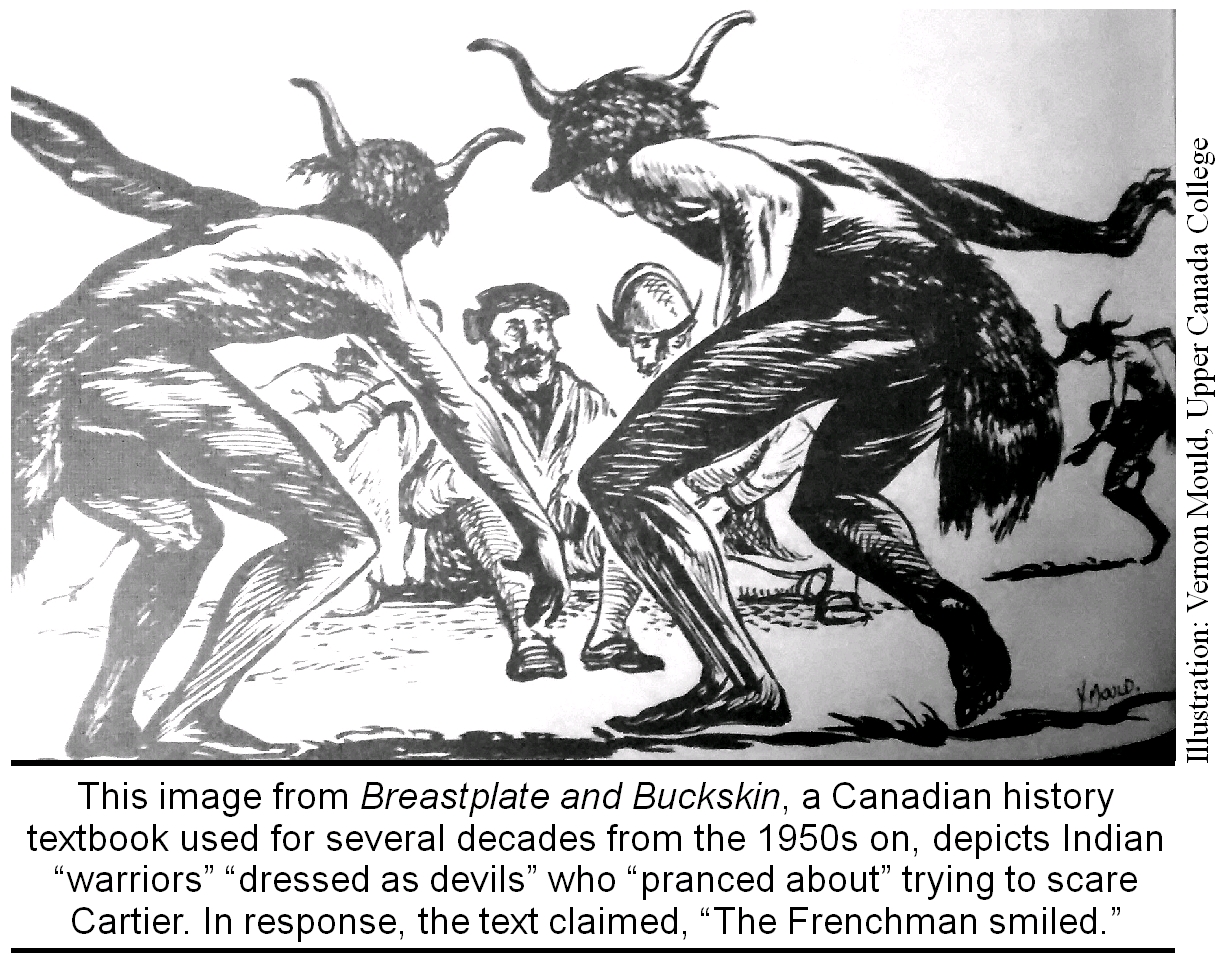

The French entertained their guests bountifully with food and drink, and, having gaily decked out two sons of the chief in French shirts and red caps, they invited these young savages to remain on the ship and to sail with Cartier.20 In his whitewashed account of Cartier’s second voyage, Leacock continued to write as if Donnacona’s sons were not prisoners. Leacock even says that Cartier was always nonviolent with Indigenous people. "It was [Cartier’s] policy throughout his voyages to deal with the Indians fairly and generously, to avoid all violence towards them," said Leacock, "and to content himself with bringing to them the news of the Gospel and the visible signs of the greatness of the king of France." Hinting that others disagreed, Leacock said the "few acts of injustice with which [Cartier’s] memory has been charged may easily be excused in the light of the circumstances of his age." This classic blame-the-victim defence, wrote off Cartier’s "few acts of injustice" as a necessary response to the supposed violence, avarice and paranoia of Canada’s savages. Cartier "could not have failed to realize the possibilities of a sudden and murderous onslaught on the part of savages," Leacock explained, because they "combined a greedy readiness for feasting and presents with a sullen and brooding distrust."21 While Miles, Dawson, Leacock and many other writers of historical fiction rendered extremely biased, blind-eye accounts of Cartier’s kidnapping of Donnacona’s sons, some more recent Canadian textbooks have actually been worse. For example, George Tait’s classic school book, Breastplate and Buckskin (1953), describes Cartier’s meeting with Donnacona without even mentioning the kidnapping. Tait’s account had no hint of controversy which previous writers at least noted in passing. On the Stadaconans, Tait wrote: These tribesmen were very friendly and showed a keen interest in trading. They were willing to give up anything they owned in exchange for metal articles... Cartier became acquainted with their chief and persuaded him to let his two sons return to France in order to learn the French language. They would be back, Cartier promised, the following year.22 Describing Cartier’s return visit, Tait says the "two Indian lads" took Cartier to Stadacona where they met Donnacona. Tait does not mention that Donnacona was the father of the "lads" who Cartier had forced into captivity.23 For 30 years, Tait’s text was used to teach Canadian history. When Tait — a professor of education at the University of Toronto — died in 2000, the Globe and Mail ran a glowing obituary. This paper, which The Canadian Encyclopedia calls "a journal of record,"24 hailed Tait’s contributions to Canadiana, saying "For three generations, school children ... studied from George Tait’s History Textbooks, grades 3 to 9." The obituary also exalted Tait by noting that "in 1971 he was presented to Her Majesty The Queen at Buckingham Palace."25 Ironically, the year that the Queen honoured Tait, the Ontario Human Rights Commission put out a scathing review of officially sanctioned textbooks. Teaching Prejudice analysed 143 social studies texts approved for use in schools. It found that "Blacks and Indians received the least favourable treatment" and that "History textbooks were the major repositories of stereotyped descriptions."26 Patrick O’Neill, a Brock University professor of education, summarised the report’s disturbing findings: Textbook portrayal of the North American Indian was distorted, denigrative, inaccurate, and incomplete. They were presented as blood-thirsty war-mongers, hostile savages and drunken thieves. They were the bad guys and the villains. In particular, textbooks contemptuously dismissed Indian religious beliefs, paid attention to Indian faults but not to Indian virtues, glossed over negative aspects of the white man’s impact, [and] discussed missionary endeavors among the Indians from only one point of view.27 Teaching Prejudice was followed by a similar studies by First Nations, academics, education ministries and human rights commissions. For example, in 1974, the Manitoban Indian Brotherhood published The Shocking Truth about Indians in Textbooks. Three years later, when Aboriginal educator Verna Kirkness summarised Canadian studies texts, she said "Indians, by far, receive the worst treatment in textbooks of any class of minority," and "recent textbooks still contain prejudice but in a more subtle manner."28 In 1982, Alberta’s Education Department issued a report called Native People in the Curriculum. It examined all 246 recommended and required learning resources for social studies in Alberta’s primary and secondary schools. Among them, "63% ... which deal with native issues were found to be either seriously problematic or completely unacceptable."29 In 1985, Brock University’s Patrick O’Neill published more research on the portrayal of natives in school resources and concluded that recent improvements were largely superficial.30 Two years later, he reviewed of ten U.S. and Canadian studies that examined dozens of kindergarten-to-college textbooks. His diagnosis was that the "status of the North American Indian in most history and social studies textbooks has not substantially improved in the last 20 years."31 In 2007, Penney Clark, a professor of curriculum and pedagogy at the University of British Columbia, and director of the national History Education Network, reviewed the depiction of Indigenous people in high school history texts from Yukon, B.C., Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia. While saying that "a transformation has taken place," she noted that the texts have not come far enough in facilitating understanding that abuses are carried out through institutional practices and have legacies within collective identities. For example, they may now acknowledge that Aboriginal people assisted European explorers and colonists but fail to acknowledge the colonial relationships of power in which such interactions occurred.32

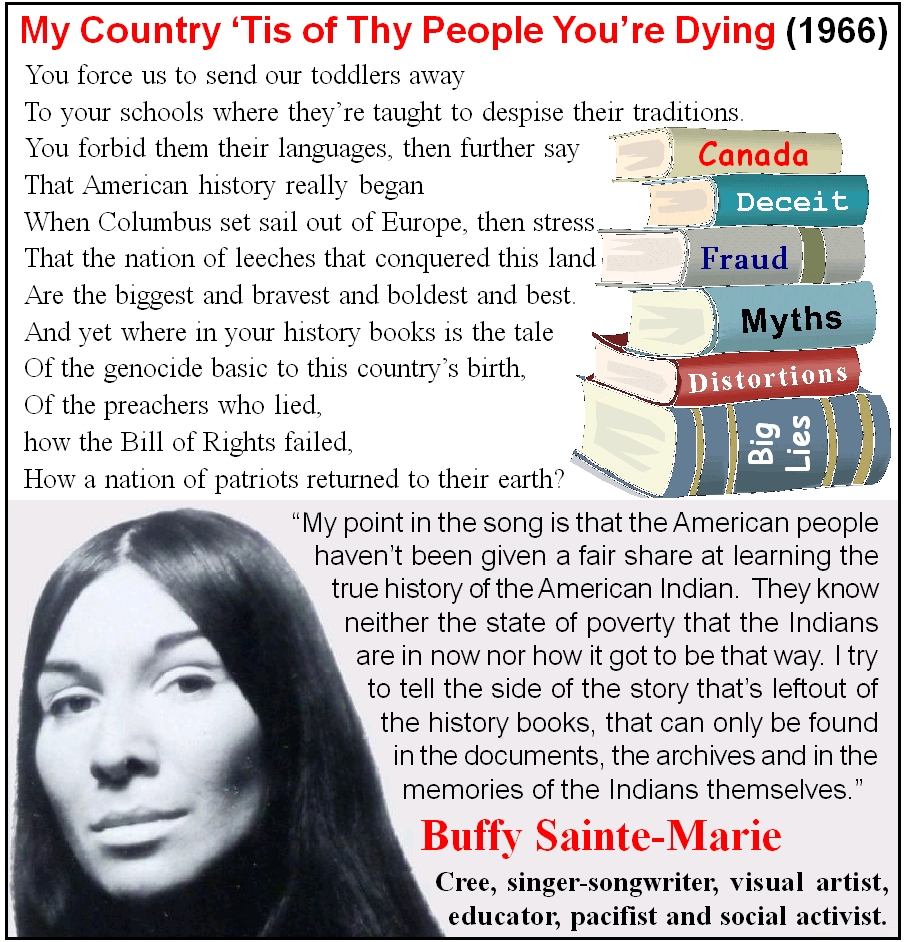

[M]ainstream Canadians see the dysfunction of Aboriginal communities but they have no idea how that happened, what caused it, or how government contributed to that reality through residential schools and the policies and laws in place during their existence. Our education system, through omission or commission, has failed to do that. It bears a large share of the responsibility for the current state of affairs.33 Sinclair challenged Canada’s Ministers of Education to change the country’s educational curricula to ensure that every single child ... is taught about the Indian Residential Schools ..., the treatment of Aboriginal people, and the historical relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people....34 Unless comprehensive changes are made to school curricula across Canada, Sinclair warned, ... I expect that I will still be approached in five, 10 or 15 years from now by people saying to me, ‘... I received my elementary, secondary and post-secondary education in this country, and I never heard a single thing about the Indian Residential Schools.’35 One solution is to add more Aboriginal voices to textbooks and learning materials. Susan Dion Fletcher, an Aboriginal faculty member in York University’s department of education, says this must include "literature written by First Nations writers and art produced by First Nations artists."36 Penney Clark notes that "the words of Buffy Sainte Marie’s protest songs could be included for analysis by student readers."37 While lyrics, poetry and myths are pigeonholed as mere works of fiction, they can contain more truth than history texts shelved as nonfiction in libraries. The truths in artistic fiction add realism to the art form, which allow us to suspend our disbelief and be entertained, or educated. History textbooks, like historical novels, contain facts that also give them the appearance of reality. The biggest difference between history texts and literary fiction may be that the former — even when riddled with outrageous biases, prejudices, misrepresentations, omissions and outright lies — pretend to be truthful accounts of reality. Once history books are blindly accepted as the authoritative truth, they become tools that define and confine how we see ourselves, our culture and nation.

1. Henry H.Miles, The History of Canada Under French Régime, 1535-1763, 1872, p.1. 2. "While Miles displays an imperialistic assumption that the French in Canada should be grateful for the perceived enlightenment brought by British rule, he also betrays a need to feel that French and English Canadians will live in harmony together." Elizabeth Galway, From Nursery Rhymes to Nationhood: Children’s Literature and the Construction of Canadian Identity, 2008, p.89. 3. Miles, op. cit., p.xxiii. 4. Ibid., p.xxiv. 5. Ibid., pp.78, 180. 6. Ibid., p.6. 7. Ibid., p.7. 8. Ibid., p.6. 9. Ibid., p.16. 10. Books by the Dawson Brothers, 1870. http://archive.org/stream/cihm_02617 11. A.J. MaGurn, "Canada’s Government printing Bureau," The Inland Printer, October 1892-March 1893. 12. George Parker, "Samuel Edward Dawson," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 2003. 13. Samuel Dawson, The Discovery of America by John Cabot in 1497, 1897. http://archive.org/stream/cihm_02612 14. Samuel Dawson, The St. Lawrence, Its Basin and Borderlands: The Story of their Discovery, Exploration, and Occupation, 1905. http://archive.org/stream/saintlawrencei00daws 15. Advertising on Canadahistory.com 16. See Henry H. Miles, "1534 Cartier Explores Canada, French Attempts at Colonization." 17. "Stephen Leacock," The Canadian Encyclopedia 18. George M. Wrong Family fonds 19. Stephen Leacock, The Dawn of Canadian History: Chronicles of Canada, Vol. 1, 1915, pp.27, 33. 20. Stephen Leacock, The Mariner of St. Malo: A Chronicle of the Voyages of Jacques Cartier, 1914, p.36. 21. Ibid., p.59. 22. George E. Tait, Breastplate and Buckskin, 1953, p.48. 23. Ibid., p.49. 24. "Globe and Mail," The Canadian Encyclopedia. 25. "Tait, George Edward," Globe and Mail, January 14, 2000. 26. Harry Dhand, A Handbook for Teachers: Research in Teaching of Social Studies, 2004, p.122. 27. G.P. O’Neill, "The North American Indian in Contemporary History & Social Studies Textbooks," Journal of American Indian Education, May 1987, p.22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24398015.pdf 28. Cited by Penney Clark, "Representations of Aboriginal People in English Canadian History Textbooks," Teaching the Violent Past: History Education and Reconciliation, Elizabeth A. Cole (editor), 2007, p.100. 29. Anne Marie Decore, Robert Carney, Carl Urion, Native People in the Curriculum: Report Summary, 1981, p.3. 30. Cited in Clark, op. cit. 31. O’Neill, op. cit., p.26. 32. Clark, op. cit., p.101. 33. Murray Sinclair, Speech to the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, July 6, 2012, p.14. 34. Ibid., p.18. 35. Ibid., p.17. 36. Susan Dion Fletcher, "Molded Images: First Nations People, Representation and the Ontario School Curriculum," in Weaving Connections (Tara Goldstein, and David Selby, editors), 2002, p.354. 37. Clark, op. cit., p.112. |

|

The

above

article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017), magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT). The

above

article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017), magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this coupon, or use the paypal link on COAT's webpage. Subscription prices within Canada: three issues ($25), six issues ($45). If quoting this article, please cite the source and COAT's website. Thanks! |

|

You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion! You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion!

Captive Canada: This issue (#68) deals with (a) the WWI-era mass internment of Ukrainian Canadians (1914-1920), (b) this community's split between leftists and ultra right nationalists and (c) the mainstream racism and xenophobia of so-called progressive "Social Gospellers" (such as the CCF's Rev.J.S. Woodsworth) who were so captivated by their religious and political beliefs that they helped administer the genocidal Indian residential school program and turned a blind eye to government repression and internment during the mass psychosis of the 20th-century's "Red Scare." (Click here to read this issue online.) Read the introductory article here: |

|

By

contrast, Miles showed great civility to the French, congratulating the Jesuits

for their noble efforts "to civilise and christianise the native Indian tribes,

by bringing them under the influence of the Church." While he noted that the

French king instructed missionaries to "spare no pains in reducing the savages

to the French habits and modes of life," Miles remarked with regret that

Catholic efforts "to train and instruct the Indian children" "were, on the

whole, unsatisfactory."5

By

contrast, Miles showed great civility to the French, congratulating the Jesuits

for their noble efforts "to civilise and christianise the native Indian tribes,

by bringing them under the influence of the Church." While he noted that the

French king instructed missionaries to "spare no pains in reducing the savages

to the French habits and modes of life," Miles remarked with regret that

Catholic efforts "to train and instruct the Indian children" "were, on the

whole, unsatisfactory."5 Besides

being a top civil servant, Dawson was also prominent within Canadian civil

society. He was a commissioner of Montreal’s Protestant School Board, active in

scientific and business councils, and was elected to the prestigious,

English-focused Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. His 1897 lectures on

"The Discovery of America by John Cabot in 1497" were published by the Royal

Society of Canada,13 of which he was later president. Dawson also wrote a

history of European explorers that praised the French treatment of "savages" and

"wild people" as "very humane." Regarding Cartier’s kidnapping of Indigenous

leaders and their children, Dawson shared Miles’ justifications of these crimes

by saying they had "the intention of treating them kindly, [and] teaching them

the Christian religion."14

Besides

being a top civil servant, Dawson was also prominent within Canadian civil

society. He was a commissioner of Montreal’s Protestant School Board, active in

scientific and business councils, and was elected to the prestigious,

English-focused Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. His 1897 lectures on

"The Discovery of America by John Cabot in 1497" were published by the Royal

Society of Canada,13 of which he was later president. Dawson also wrote a

history of European explorers that praised the French treatment of "savages" and

"wild people" as "very humane." Regarding Cartier’s kidnapping of Indigenous

leaders and their children, Dawson shared Miles’ justifications of these crimes

by saying they had "the intention of treating them kindly, [and] teaching them

the Christian religion."14 Leacock

also contributed a volume to Wrong’s Chronicles of Canada, which

glorified Jacques Cartier. Removing from the historical record Cartier’s

admission that his men seized Donnacona and sons, and forcibly took his boys

captive to France, Leacock offered this glowingly deceitful rendition:

Leacock

also contributed a volume to Wrong’s Chronicles of Canada, which

glorified Jacques Cartier. Removing from the historical record Cartier’s

admission that his men seized Donnacona and sons, and forcibly took his boys

captive to France, Leacock offered this glowingly deceitful rendition:

In a

speech to Canada’s Council of Ministers of Education in 2012, Justice Murray

Sinclair, then chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, was critical of

Canada’s educational system:

In a

speech to Canada’s Council of Ministers of Education in 2012, Justice Murray

Sinclair, then chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, was critical of

Canada’s educational system: References

References