Fictive Canada:

Issue #69,

Press for Conversion! (Fall 2017)

Click here

for info about symbolism of the front-cover collage |

|

|

Table of Contents 1-

True Crime Stories and

2-

John Cabot & Britain’s Fictitious Claim on

Canada: > Why “The Dominion of Canada”?

3-

Canada’s Extraordinary Redactions:

4-

Textbook Cases of

Canadian Racism:

5-

From Popes and Pirates to Politicians and

Pioneers: >

The Canadian Legal Fiction of

6-

Breaking the Bonds

of

>

Oh say can you see? Blindsport

for Peaceable Racism

7-

Native

Captivity and Slave Labour 8-

Child Slavery in Canada’s

>

Jean L’Heureux:

|

Breaking the Bonds of Ignorance and Denial: Slavery, Genocide, Historical Fiction and other Canadian Values

View this article from

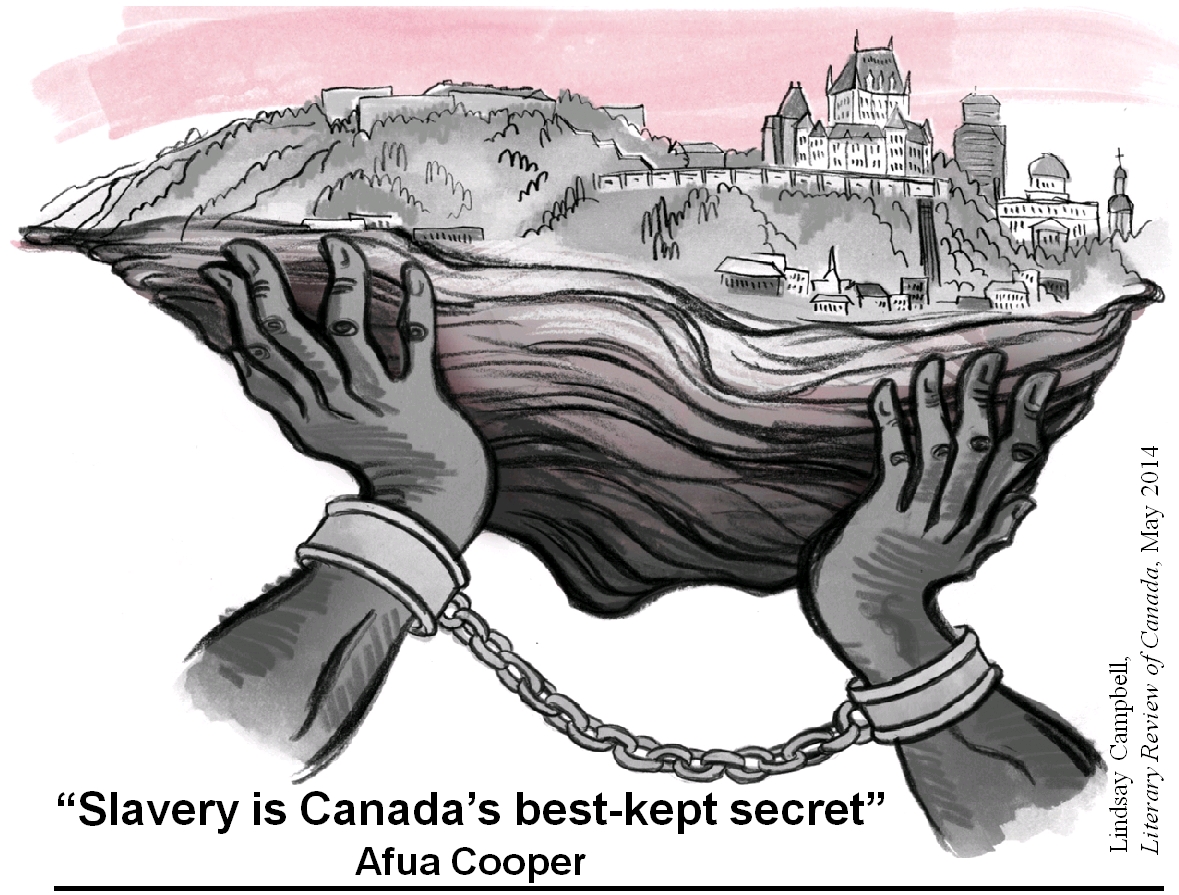

Fictive Canada (pp.30-42) in PDF format For hundreds of years, most Canadians and their leaders — legal, religious and political — valued the institution of slavery as a norm of society. This ugly blot on Canada’s heritage contradicts the grand, self-congratulatory myth that this country is a Peaceable Kingdom, infused to its core with such blessed traits as multiculturalism, human rights and social justice. To this day, although supposedly enlightened by these much-heralded "Canadian values," this country remains haunted by the spectre of its little-known history of slavery. Slavery is one of the abhorrent realities of Canadian heritage that is hidden behind grand national myths. Although for generations, Canadian laws and religious mores enshrined and sanctified the business of human bondage, this reality is now all but forgotten. When it comes to recognising this history, Canada is still enslaved by ignorance, amnesia and denial. How was Canadian slavery justified and legitimized for so long before being buried and forgotten? Learning this history may help emancipate us from the hypocrisies that continue to hold so many Canadians hostage. By freeing ourselves from the blinding myth that Canada is built on such noble values as human rights and multiculturalism, we may see through the captivating veils of deception that still colour the blissfully rosy image of our country as a Peaceable Kingdom. Uncovering our little-known history of slavery are academics such as Afua Cooper, the chair of Black Canadian Studies at Dalhousie University in Halifax. "Slavery," she says, "is Canada’s best-kept secret, locked within the national closet. And because it is a secret it is written out of official history."1 Cooper, a Jamaican-born Canadian, goes on to lament that Scholars have painted a pristine picture of Canada’s past. It is difficult to find a scholarly or popular publication on the country’s past in which images, stories, and analyses of slave life are depicted .... It is possible to complete a graduate degree in Canadian studies and not know that slavery existed in Canada.2 To explain why this history has been "suppressed or buried," Cooper says "slavery has been erased from the collective unconsciousness" because this "ignoble and unsavoury past" serves to "cast Whites in a ‘bad’ light." As a result, she says, the "chroniclers of the country’s past, creators and keepers of its traditions and myths, banished this past into the dustbins of history."3 |

|

George Clarke, a Nova Scotian poet and playwright, has also decried Canada’s naive, self-glorifying image: The avoidance of Canada’s sorry history of slavery and racism is natural. It is how Canadians prefer to understand themselves: we are a nation of good, Nordic, ‘pure,‘ mainly White folks, as opposed to the lawless, hot-tempered, impure mongrel Americans, with their messy history of slavery, civil war, segregation, assassinations, lynching, riots, and constant social turmoil. Key to this propaganda — and that is what it is — is the Manichean portrayal of two nations: Canada, the land of ‘Peace, Order and Good Government’ … where racism was not and is not tolerated, versus the United States of America, the land of guns, cockroaches, and garbage, of criminal sedition confronted by aggressive policing (and jailing), where racism was and is the arbiter of class (im)mobility.5 But there is a "price" to be paid, Clarke says, for Canada’s "flattering self-portrait" and that "price … is public lying, falsified history, and self-destructive blindness."6 Enslaved by Canada’s Underground-Railroad Myth A popular self-image held dear by many Canadians is that this country was a safe haven for American slaves. "The Underground Railroad," says Abigail Bakan, "is commonly understood as a defining moment in the ideology of the Canadian state regarding the legacy of racism and anti-racism." But as Bakan, the chair of Gender Studies at Queen’s University, has pointed out, Canada was "far from a Promised Land."7 Refrains from the sacred Canadian hymnal about the Underground Railroad, repeat the cherished chord that fugitive slaves were warmly welcomed citizens of the "True North Strong and Free." Unfortunately, the Great White North’s history has been coloured to match what Clarke has called Canada’s "flattering self-portrait." As Bakan has noted: popular understanding and retelling of the Underground Railroad story, Canada is presumed in its origins and early history as a nation consistent with modern notions of inclusiveness and multiculturalism.8 However, this self image does not match historical reality. As Queen’s University gender studies professor Katherine McKittrick has noted, Canada’s Underground Railroad history is central to the nation’s legacy of racial tolerance and benevolence .… In a post-slave context, this history has been extremely significant in the production of Canada’s self-image as a white settler nation that welcomes and accepts non-white subjects. It has been one of the more important narratives bolstering perceptions of Canadian generosity and goodwill…. This history of benevolence, conceals and/or skews colonial practices, Aboriginal genocides and struggles, and Canada’s implication in transatlantic slavery, racism, and racial intolerance. That is, the Underground Railroad continually historicizes a national self-image that obscures racism and colonialism through its ceaseless promotion of Canadian helpfulness, generosity, and adorable impartiality.9 Afua Cooper has also tried to correct Canada’s self-righteous anti-slavery myths by saying we associate Canada with ‘freedom’ or ‘refuge,’ because … between 1830 and 1860 … thousands of American runaway slaves escaped to and found refuge in the British territories to the north. [T]he image of Canada as ‘freedom’s land’ has lodged itself in the national psyche and become part of our national identity. One result is the assumption that Canada is different from and morally superior to that ‘slave-holding republic,’ the U.S.10 The idea that Canada was "a prejudice-free haven at the end of the Underground Railroad, ... waiting to receive slavery’s oppressed victims," is a "popular myth"11 said historian Allen Stouffer of St. Francis Xavier University. In truth, for more than a century after Britain outlawed slavery, racism was the law in Canada. Blacks and Asians were all but banned from entering Canada until 1967 when the "race" barrier was finally removed from our immigration laws. Racial segregation in schools was legal in Ontario and Nova Scotia until the 1960s. Segregation was also imposed in the military, and by various churches, orphanages, poor-houses, hospitals, hotels, restaurants, theatres, parks, pools, beaches, dance halls, rinks and bars.12 Despite this, "most Canadians could deny to themselves that Canada had a ‘race’ problem," said political scientist Jill Vickers. In Canada, she noted, "the majority of Whites supported segregation" and "Canada’s ‘dirty little secret’ enjoyed widespread, if covert, support."13 To derail the prevailing train of thought about Canada’s underground-railway, we must put this popular myth into reverse. Climb aboard as we look at slaves who escaped bondage in Canada to gain freedom in the US. Canada’s Reverse Underground Railroad? During the final decades of the 1700s and the first decades of the 1800s, some slaves in Canada dreamed of fleeing captivity by escaping to the US! The existence of this "reverse Underground Railroad" would surprise those who cherish the notion that Canada was always a sanctuary for runaway slaves. Although Britain, and hence Canada, did finally abolish slavery in 1834, it had by then already been in remission in parts of the American northeast for almost 60 years. Vermont began to ban slavery in 1777, followed by Pennsylvania in 1780 and New Hampshire in 1783. Massachusetts then completely outlawed slavery, while Connecticut and Rhode Island began to follow suit in 1784. Within three years, slavery was abolished in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota. Lagging far behind was New York, which stalled until 1799 when it began the process of abolition. But Canada was much farther behind. Our government lagged another 35 years until the order to ban slavery finally came from Britain in 1834.14 For years then, while Canada held on to slavery, New England was a land of relative freedom. Those enslaved by Canada’s romanticised legends of the Underground Railroad would be surprised to learn that some Canadian slaves escaped their bondage here to find freedom in the US. Cooper notes that "in Detroit, for example, a group of former Upper Canadian slaves formed a militia in 1806 for the defence of the city against the Canadians." Some former Canadian slaves soon took up arms to protect Detroit from attacks by Canadian forces during the War of 1812.15 Detroit, named after the French word for strait (d’étroit), had previously been within the bounds of New France. As part of the French Empire in North America, it too was deeply ensconced in the system of slavery that pervaded western European society.

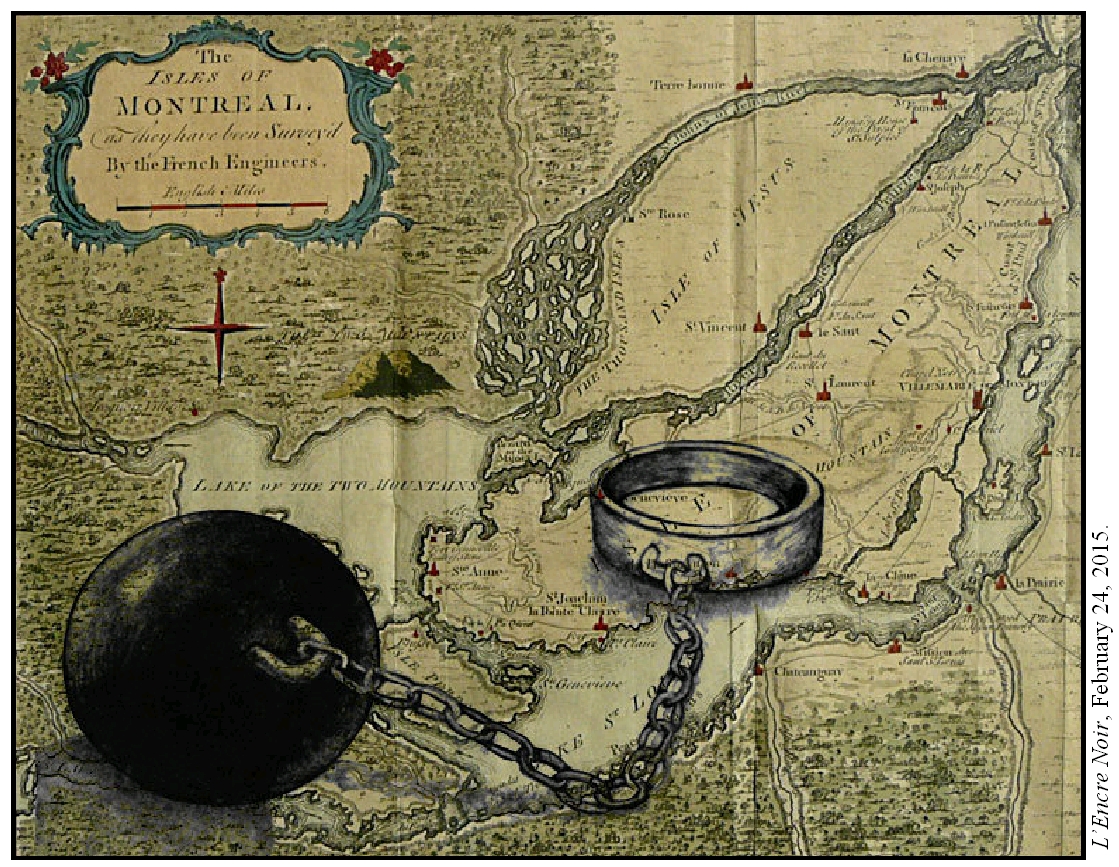

Although slavery in New France, said historian Marcel Trudel, "had an official, legal existence over two centuries ... between 1632 and 1834,"16 it is still practically unknown to Canadians. Throughout his career, Trudel tried to expose this lost history. "How can slavery in Canada have been virtually forgotten?" he asked in 2013. "Historians are surely to blame, whether because they did not examine slavery or because they failed even to notice it."17 Trudel pointed to an " influential nineteenth-century nationalist historian," Francois-Xavier Garneau,18 who "completely misinformed" readers" with an "extraordinary distortion of historical truth!" Trudel reveals that Garneau not only "claimed that slavery in Québec was largely a British institution," he also "claimed the clergy had consistently opposed slavery." Finally, Trudel lambasts Garneau for having "left out all mention of ‘savage’ slaves." The result, said Trudel, was that Garneau’s "erroneous description of slavery" helped "society forget the institution had ever existed here."19 Trudel exposed three main fictions about Canadian slavery perpetuated by Garneau and others since. Firstly, among the documented slave owners, 85.5% were Francophone and 14.5% were Anglophone.20 Secondly, regarding alleged church opposition to slavery, Trudel "could not find any single instance where the clergy opposed introducing blacks into Canada." In fact, he noted that "in 1720, religious communities joined the rest of the population in petitioning Intendant Begon to allow them to import hundreds of blacks."21 Finally, Trudel’s research showed that Indigenous slaves "far outnumbered black slaves."22 But Canada’s ignorance of slavery is not the fault of historians alone. As Trudel’s publisher noted, his research documents Canadian politicians, historians and ecclesiastics who deliberately falsified the record, glorifying their own colonial-era heroes, in order to remove any trace of the thousands of Aboriginal and Black slaves held in bondage for two centuries in Canada.23 In his book Canada’s Forgotten Slaves (2013), first published in 1960, Trudel observed that the history of slavery in Canada is "still relatively unknown" and that "we are still met with surprise" and "disbelief" that slavery ever existed here. Although the "version of Québec history we have long been told was all about missionaries and spiritualists," he remarked, "our colonial past can be likened to the Thirteen Colonies of America."24 This blissful ignorance is not new. Trudel noted that slavery left "few traces in the collective memory and literature of Quebec," and only "scattered references" are found in 19th century Québec literature. "Our novelists," he lamented, "never noticed the presence of slaves" and only one "ever bothered to mention slaves."25 Trudel delved into historical documents to expose lost details of Canadian slavery. He found data on 4,185 slaves, largely in the civil registries of Catholic and Protestant churches which noted slaves if they were baptized. These records however are incomplete because "no law compelled owners to baptize their slaves and they were in no hurry to do so."26 One of the significant but little known facts about slaves in New France is that most were Indigenous. Of the 4,124 documented slaves whose race was recorded, 35 percent were Black, while 64 percent, including 339 children, were Indigenous.27 Most slaves died young. On average, Indigenous slaves did not even survive to age 18, while Black slaves usually died by the time they were 25 years old.28 Although "the institution of slavery in Canada was first recognized and amply protected by French law," Trudel points out that slavery was "extended under the British regime" after the 1760 Conquest of New France.29 The 47th Article of Capitulation stated Negroes and Panis of both Sexes shall remain in possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong; they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the Colony or sell them; and they may also continue to bring them up in the Roman religion.30 While Francophones were more likely to own Indigenous slaves, Anglophones favoured Black ones. During the American Revolution (1765-1783), the number of Black slaves in Canada "rose suddenly to well over 600." This is because when British Empire Loyalists fled north to be warmly welcomed into Canada, the government was happy to let them bring all their property, including their slaves.31 Indigenous slaves were known as panis because so many of them had been kidnapped from the Pawnee nation in what is now Nebraska, Oklahoma and Kansas. As Jacques Raudot, the intendant who ran the civil administration of New France, wrote in 1709: It is well known the advantage this colony would gain if its inhabitants could securely purchase and import the Indians called Panis, whose country is far distant from this one .... [T]he people of the Panis nation are needed by the inhabitants of this country for agriculture and other enterprises that might be undertaken, like Negroes in the [Caribbean] Islands.32 Over 85% of New France’s Indigenous slaves, whose origins are now known, were taken captive in the Mississippi River basin.33 Although not all these slaves were Pawnee, the term panis was a generic term for all Indigenous slaves. The slaves of New France were most visible in its large urban centres, where 61 percent of all known slaves were held.34 Research by Brett Rushforth, a historian at the University of Oregon, has revealed that by 1709 about 14 percent of all Montreal households owned an Indian slave. Rushforth also found that panis were most common in Montreal’s commercial zone. In this area of the city "half of all colonists who owned a home in 1725 also owned an Indian slave."35 While Québec City had 38 percent of known urban slaves, "Montreal led the way," says Trudel, with 60 percent. Many were "acquired from Amerindian nations through the fur trade, Montreal’s economic lifeblood."36 The Slave / Fur Trade A little-known reality of Canada’s Indigenous slave trade is its close connection to the fur trade. In fact, the trade in furs and the trade in Indigenous slaves were not really two separate businesses. They were actually just two sides of the same very lucrative coin. Trudel hinted at the link between the trade in furs and slaves when remarking that slave owners were largely found in four professions: "colonial officials, military officers, explorers and fur traders." These "key groups," he said, "defined the heyday of slave-owning" in Canada because they were the "most intimately involved with native Amerindian nations."37 Trudel found records showing that at least 38 voyageurs had 73 slaves, while 35 fur traders owned 112.38 Two of the latter made it onto Trudel’s list of Canada’s thirty "leading slave owners": Jacques-François Lacelle with 16 slaves, and Louis Campeau with 11.39 Documented slaves reached a peak of about 500 between 1740 and 1760. Trudel attributed this to the importance of the fur trade, which made it easier to acquire Amerindian slaves. With the decline of the fur trade, the number of Amerindian slaves then quickly fell off.40 While Trudel did not delve into the links between fur trading and slavery, Rushforth gives many details. Before European contact, some First Nations had a tradition of exchanging gifts — including captured enemies — as a form of ritualised diplomacy to cement alliances. Rushforth notes that Indian allies of New France initially offered a few captives "from their western enemies ... as symbolic gifts to French merchants associated with the fur trade."41 While First Nations saw this as a way to "negotiate peace" and "strengthen friendships," French traders were motivated by strictly commercial goals. Seeking profits, they encouraged their Indian allies to capture more and more slaves.42 Andre Penicaut, who lived in France’s American colonies from 1699 to 1721, reported in his account of the year 1710 that French-Canadians living among the Kaskaskia Illinois were inciting the savage nations ... to make war upon one another ... in order to get slaves that they [the French] ... sold to the English. Rushforth notes that French coureurs de bois and their First Nations’ partners, spent much of the 1710s "working with Carolina traders to bring slaves and furs from the western Ohio Valley to southeastern English ports."43 The colonial administrators of New France saw this movement of pelts and slaves to British markets on the Atlantic coast as a threat not only to French business interests but to their strategic alliances with First Nations. These military ties were vital to France’s ongoing war with the Britain to control North America. Rushforth cites an English mapmaker and author, Jonathon Carver, who recorded in his 1789 journal that the French colony’s increasing demand for Indigenous slaves "caused the dissensions between the Indian nations to be carried on with a greater degree of violence, and with unremitted ardor."44 "As French colonists demanded a growing number of Indian slaves from their allies," said Rushforth, "Native American captive customs also evolved to meet the new realities of New France’s slave market." With the increasing demand for slaves, "Indian nations increasingly viewed captives as commodities of trade," explained Rushforth, "rather than as symbols of alliance, power, or spiritual renewal," or as a means to "build union and foster peace." The slave trade was certainly a depraved and corrupting force. Because it "rewarded brutality with valuable goods," said Rushforth, the French appetite for more and more slaves "encouraged the colony’s [Indigenous] allies to choose warfare over peace."45

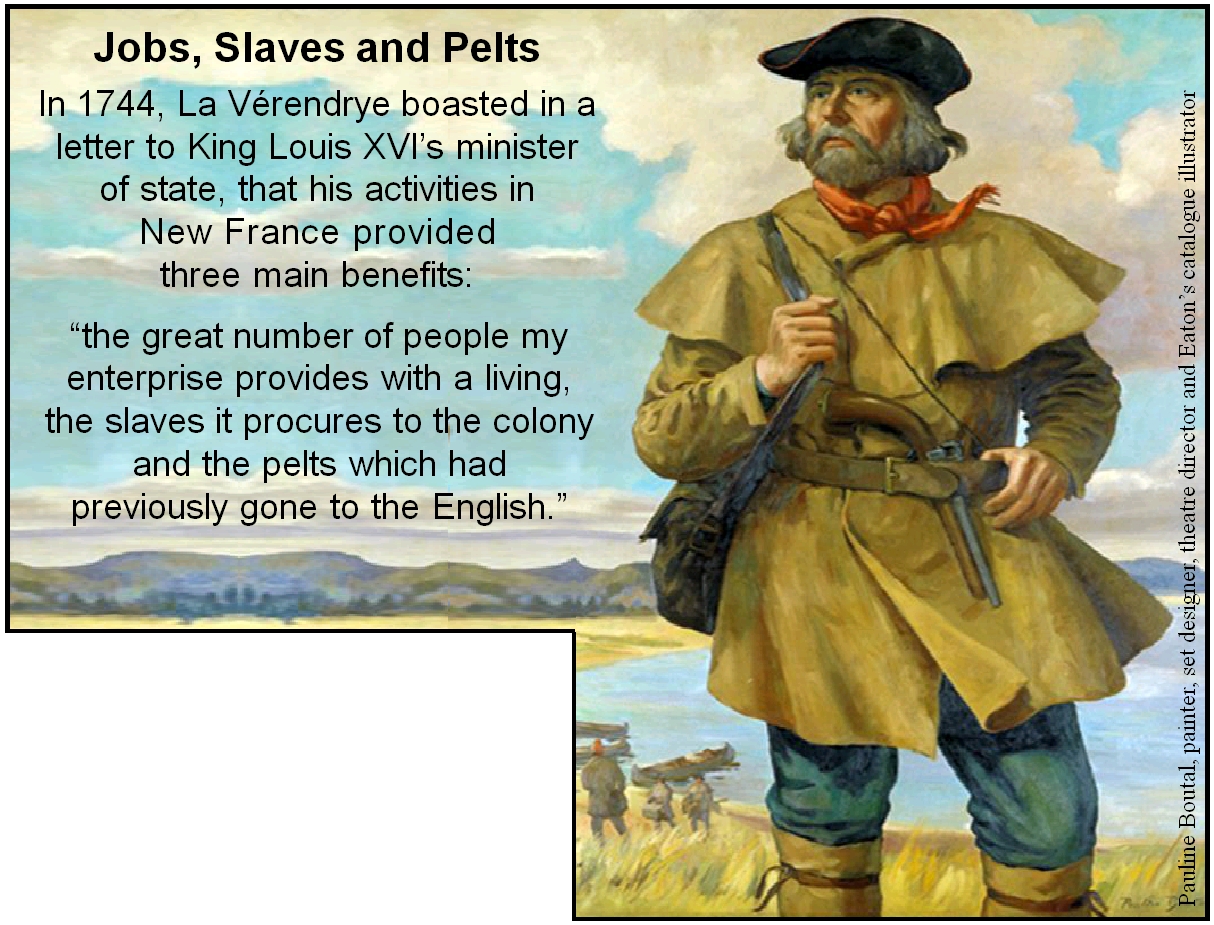

While La Vérendrye is portrayed in countless sources as a heroic figure who "opened up" western Canada, little is ever said — outside a few scholarly articles — about his pivotal role in "opening up" Canada’s slave trade. Legends about La Vérendrye have been perpetuated in many popular fictions, including Canadian history textbooks. As Karlee Sapoznik, a York University historian, has said: the historiographical literature which focuses on his travels and turbulent interactions with Aboriginal peoples is incomplete, for it is marked ... by a tradition of denial and mythology surrounding the French-Canadian slave trade.46 Trudel showed that La Vérendrye had three or more personal slaves, and that his sons owned at least six.47 This however is trivial compared to his overall role in the acquisition and sale of Indigenous slaves through the fur trade. For example, in 1742, La Vérendrye acquired a particularly large number of slaves. Claude-Godefroy Coquart, a Jesuit missionary who was accompanying La Vérendrye’s western business trip, wrote that their Cree and Assiniboine allies had killed 70 Sioux men plus an undisclosed number of women and children. During their four-day battle, they also captured so many slaves that Coquart said it formed a line four arpents long.48 (Since an arpent was 192 feet, the line of captives from this battle measured 768 feet!) When Governor of New France, Marquis de Beauharnois, reported this to Louis XVI’s chief minister, the Comte Maurepas, he said "this will not be good for La Vérendrye’s affairs for he will have more slaves than bundles of fur."49 But despite close ties to the horrors of the slave trade, La Vérendrye’s name can be found across the cultural landscape on street signs, schools, a hospital, a river and provincial park in Ontario, an electoral district in Manitoba, a mountain in B.C., and a 12,600 sq.km. wildlife preserve in Québec that contains two First Nation communities. La Vérendrye’s "memory is especially honoured and celebrated" in Manitoba, says the Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America, during "commemorative festivities, cultural events and the arts." This online source not only heralds La Vérendrye as "a symbol of courage and the spirit of adventure," but also as "the archetypal ideal of the voyageur who ... discovered new waterways and deftly ran a fur trade operation ...." It also falsely conflates his brand with Canada’s mythology of multicultural unity by saying that "La Vérendrye is alive and well in the shared memories of a variety of cultures and communities — French, English, Métis and Native alike."50 La Vérendrye’s noble visage is also commemorated in countless paintings, statues and civic monuments, as well as on a Canadian postage stamp, and on 1,000 solid gold coins produced by the Royal Canadian Mint in 2016. Although marketing for these $2,000 coins, in the "Great Canadian Explorers Series," says that it "[h]ighlights the fundamental role of Aboriginal people in Canada,"51 there is no hint that La Vérendrye’s line of work used warfare to capture Indigenous slaves. La Vérendrye did not hide his involvement in the despicable business of slavery. He was in fact proud of his work supplying Indigenous slaves to the urban markets of Montreal and Québec. La Vérendrye’s boastfulness about building the empire for his French colonial masters was expressed in his 1744 letter to Louis XVI’s minister of state, Maurepas. In describing his valuable contribution to king and colony, La Vérendrye bragged that there were three main benefits to the vast commercial venture that he founded and commanded. He listed these as: the great number of people my enterprise provides with a living, the slaves it procures to the colony and the pelts which had previously gone to the English ....52 To this, Trudel remarked that by listing jobs, slaves and furs, in that order, La Vérendrye was declaring that he "considered slavery to be the second advantage in importance, ahead of furs."53 Despite decades of research by a few leading scholars, the closely intertwined history of fur trade with the trade in Indigenous slaves is still unknown to most Canadians. Mainstream history sources must share the blame for this collective amnesia. Let’s look at three key examples that completely whitewash this facet of history: The Canadian Encyclopedia, the Canadian Museum of History, and the Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America. None of these sources even mention slavery in their material on the fur trade.54 The Canadian Encyclopedia downplays Indigenous slavery in Canada. While its main article on slavery, called "Black Enslavement in Canada," does include limited information on Indigenous slaves, it makes no mention of the fur trade.55 Likewise, the Museum of History’s webpage on slavery also neglects any reference to the fur trade.56 While the Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America does not have any articles on slavery, a few of its entries do mention, in passing, that slaves existed in New France particularly those of African origin held captive in Louisiana.57 Although these sources boost the La Vérendrye’s image as a great "explorer," they say nothing of his complicity in the business of seizing and selling Indigenous people as slaves.58 The fact that Canadian history generally overlooks La Vérendrye’s role in ‘opening up’ the slave trade is mentioned in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. It notes that "Most historians ... for reasons which are not too difficult to understand, have preferred to ignore this aspect of his career."59 It is however "difficult to understand" why Indigenous slavery and its links to the fur trade, goes unmentioned on the web sites of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The AFN website does not reference Canada’s two-centuries of trade in Indian slaves, or its ties to the fur trade.60 While the TRC website repeats two general references to the African slave trade,61 and an honorary witness mentioned slavery in Nazi arms factories,62 it gives no information about the slave trade in Canada. Although the TRC’s final report does cite statements by the UN and the United Church of Canada which mention that Europeans enslaved Indigenous people, the TRC does not say that this happened in Canada, let alone provide any details.63 Exporting Slaves to the War Galleys of France

This story of treachery and intrigue opens with a letter written in 1684 by King Louis XIV to Joseph-Antoine de La Barre, then Governor General of New France. In his letter, the king approved La Barre’s plan to attack the so-called "Iroquois Savages," and agreed to send another ship with 300 more soldiers. The king told La Barre that he wanted to furnish you means to fight advantageously, and to destroy utterly those people, or at least to place them in a state after having punished them for their insolence, to receive peace on the conditions which you will impose on them.64 His goal, the king said, was "to diminish as much as possible the number of the Iroquois" in New France. "[T]hese savages, who are stout and robust, will," said the king, "serve with advantage in my galleys." He then urged La Barre "to do everything in your power to make a great number of them prisoners of war, and ... have them shipped by every opportunity ... to France."65 Being a galley slave aboard one of France’s ships of war was a fate worse than death. Galleys were then rowed by prisoners from French jails and from the religious war being fought against protestant Huguenots. Describing the 17th century as "the great age of the galleys," and noting that Louis XIV’s galleys had a "particularly bad reputation," historian W.H.Lewis (brother of novelist C.S. Lewis) said: Until the coming of the concentration camp, the galley held an undisputed pre-eminence as the darkest blot on Western civilization; a galley, said a poetic observer shudderingly, would cast a shadow in the blackest midnight.66

France’s war against the Haudenosaunee envisioned the destruction of "all their plantations of Indian corn." He also said their villages would be "burnt, their women, their children and old men captured and other warriors driven into the woods where they will be pursued and annihilated by the ... savages" allied to the French.68 In March, the king approved Denonville’s plan saying he looked forward to "the entire destruction of the greater part of those savages" before year’s end. To this he added that "as a number of prisoners may be made .... His Majesty thinks he can make use of them in his Galleys." Then, he asked Denonville to "send those which have been captured," noting that they would "be of great utility."69 The governor launched his plan with a grand deception, not only of the Haudenosaunee but of Jesuits who had been trying to convert them to Catholicism. The insidious scheme used the pretense of peace to entrap Haudenosaunee leaders and throw them into the hellish slavery of France’s war galleys. Denonville used a missionary named Jean de Lamberville to lure Haudenosaunee chiefs into a trap at Fort Frontenac in Cataracouy, now Kingston, Ontario. Lamberville, who had been working among the Haudenosaunee for 18 years, had managed to win some confidence among them. Using the naive Jesuit’s confidence, the governor’s devious scam worked. Father Lamberville was called to Montreal from his mission among the Onondaga, a member nation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in present-day New York. He was then conned by Governor Denonville into believing that the colonial authorities wanted peace and reconciliation. Denonville provided him with numerous presents for the tribesmen, commissioned him to invite representatives from the Confederacy to a parley at Fort Frontenac and seemed to accept Lamberville’s conciliatory views. Denonville wrote, ‘This poor father does not suspect our design. He is a clever man; but if I recalled him from his mission our purpose would be suspected and the storm would burst on us.’70 Although his letter from Versailles said "His Majesty has approved ... calling the Iroquois nations together at Cataracouy," the king wanted to protect Lamberville from being "exposed to the fury of those Savages."71 Denonville risked the Jesuit’s life by keeping him in the dark. Lamberville survived thanks to his captor’s faith that he had been duped into being an unwitting shill in this imperial con game. While initiating this plan to enslave unsuspecting Haudenosaunee chiefs, Denonville was also secretly preparing a sizable army to attack their villages. In June, he left Montreal with 830 soldiers from France, over 1000 Canadian militia and 300 Indians, "including a large contingent of Christian Iroquois from the mission towns near Montreal." Along the way, when joined by 160 coureur de bois and nearly 400 from the Ottawa nation, their total reached about 2700.72 In describing the unleashing of this force, U.S. historian Francis Parkman wrote in 1877 that the: governor issued a proclamation, and the bishop a pastoral mandate. There were sermons, prayers, and exhortations in all the churches. ... The church showered blessings on them as they went, and daily masses were ordained for the downfall of the foes of Heaven and of France.73 Meanwhile, Lamberville had convinced "forty-nine chiefs, numerous pine tree chiefs, and two hundred women including clan mothers" to attend the supposed peace conference in early July. Expecting a festive negotiation with the governor and lavish gift exchanges to finalise their much-desired peace treaty, the Haudenosaunee envoys were seized by troops. Denonville also "allowed his soldiers to loot the many gifts of furs and food that the Haudenosaunee were bringing to the conference to seal their goodwill."74 Denonville’s violent breach of trust did not end there. Some Haudenosaunee villagers living close to Fort Frontenac, who had long been friendly the French, were also invited to a "feast." When "thirty men and ninety women and children" arrived to celebrate, Parkman says "they were surrounded and captured by the intendant’s escort and the two hundred men of the garrison." Then, "a strong party of Canadians and Christian Indians," were sent out to "secure" the villagers of nearby Ganneious [now Napanee, Ontario]. They soon returned with 18 men and 60 women and children captives. Other Haudenosaunee were also "offered the hospitalities" of the fort and some were "caught by the troops." These hostages included "Indian families" of men, women and children who Parkman surmised had also been "urged ... by the lips of Lamberville, to visit ... and smoke the pipe of peace."75 The treatment of these kidnap victims was grisly. Using the first hand account of Louis Lahontan, Parkman described the scene in Fort Frontenac: A row of posts was planted across the area ... and to each post an Iroquois was tied by the neck, hands, and feet.... A number of Indians attached to the expedition, all of whom were Christian converts from the mission villages, were amusing themselves by burning the fingers of these unfortunates in the bowls of their pipes, while the sufferers sang their death songs.76 Of the more than 150 captured women and children, said Parkman, "many died at the fort." The survivors were "baptized, and ... distributed among the mission villages in the colony." The men were sent to Quebec City where some of them were given up to their Christian relatives in the missions who had claimed them, and whom it was not expedient to offend; and the rest, after being baptized, were sent to France, to share with convicts and Huguenots the horrible slavery of the royal galleys.77

Bishop Saint-Vallier was no stranger to holding Indigenous people captive. In fact, this bishop owned his own personal panis, a young slave named Bernard, who he brought to the Hotel-Dieu de Quebec in 1690.79 Ironically, Saint-Vallier was later taken hostage himself. In 1704, he was captured at sea and — though not forced into slavery, let alone aboard a French war galley — he was put under house arrest for five years in England by Queen Anne who used him as a bargaining chip to gain the release of Baron de Méan, the dean of Liège, France.80 After baptising and enslaving the Haudenosaunee’s peace envoys and "distributing" hundreds of Indigenous women and children to the already converted "mission villages," Gov. Denonville continued his brutal war against the Haudenosaunee. His army went on a rampage, burning and looting Seneca towns and villages of the Confederacy. They not only destroyed fields and what Denonville estimated to be 1.2 million bushels of cached corn, they also desecrated Haudenosaunee cemeteries by destroying their religious symbols and even pillaged the corpses for grave goods.81 The kidnappings at Fort Frontenac, the enslavement of peace envoys and the devastation of Seneca communities, provoked the Haudenosaunee to respond. Counterattacks included assaults on Canada, including one against Lachine in Montreal where 24 were killed and 70-90 taken prisoner. "The Governor of Canada has started an unjust war against all the [five allied] nations," a Mohawk orator was recorded as saying, and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy have "desired to revenge the unjust attacks."82 In 1688, Denonville and his Attorney General Ruette d’Auteuil, asked Louis XIV to allow the colonists of New France to import African slaves. The king granted this on May 1, 1689. Ironically, almost 200 years later, May 1 was first celebrated as International Workers’ Day. May Day activists made radical demands such as an 8-hour work day and an end to child labour. The epicentre of this movement was Chicago, Illinois, where 100,000 went on strike in May 1886.83 Although "wage slavery" was central to their rhetoric, they did not know that May 1 was when, two centuries earlier, it became legal to import African slaves to New France, which then included Chicago. Christianity and Slavery Whenever European monarchs delegated military, political and economic agents to sally forth and extend their empires, the quest for profits from the slave trade was rarely far behind. For many centuries, the holy institutions of Christendom aided this grand imperial enterprise by furnishing the finest of rationales to promote slavery. In fact, for most of its 2,000-year history, the Church supplied the key doctrines justifying the ethics of human bondage. As the encyclopedia Africana states: It is a major irony of world history that Christianity, which teaches the fundamental equality of all souls before God, condoned for 1800 years the most unequal of all institutions. The early Church Fathers declared that slavery was a punishment for original sin. Medieval theologians accepted enslavement of prisoners in what they classified as ‘just’ wars. In the fifteenth century the pope denounced the enslavement of Christians, while explicitly offering up ‘pagans’ as fair game.84 With these Christian excuses in hand, and in mind, well-meaning churchgoing slave owners and traders could rest easy in the comforting faith that their complicity in the business of buying, selling and owning slaves was condoned by the Church and by god. Besides validating the legitimacy of slavery for almost two millennia, the Church also practised what it preached. Throughout this period, Christian leaders and their institutions were counted among the slave-owning elite. In New France, "[s]lavery was a formally established institution," explained Trudel, "and as such the highest authorities in the colony, both secular and religious, owned slaves." As for the colony’s highest religious authorities, Trudel’s research "established that senior ecclesiastics, bishops, priests, religious and members of religious communities all owned slaves."85 By examining the biographies of the four Bishops named by Trudel, we can see that they occupied Catholicism’s highest rank in Québec for almost nine decades: Bishop Saint-Vallier (1685-1727), Bishop Dosquet (1733-1739), Bishop Pontbriand (1740-1760), and Bishop Plessis (1806-1825).86 The slave-owning clergy listed by Trudel included two Sulpicians, a Recollet and four secular priests from St-Augustin (Québec City), St-Cuthbert (Montréal), Detroit and Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu (near Montréal).87 Besides individual priests, religious orders in New France also held at least 100 slaves. These included Jesuit communities in Québec City, the Seigneury of Sault St. Louis (on land taken from the Mohawks of Kahnawá:ke south of Montreal), the parish of Saint-François-du-Lac near Trois Rivières, and several missions in what is now the US. These Jesuits had at least 46 slaves. Other slave-owning religious communities were the Séminaire de Montréal and the Brothers of Charity at Louisbourg in Nova Scotia.88 Two religious communities are on Trudel’s list of the top slave-owning groups in New France. His list of the colony’s thirty leading slave owners, included the Jesuits, and the Seminaire de Québec which had 31 slaves.89 Canadian nuns also held slaves, including those who ran two hospitals: the Hôpital-Général in Québec City which had an Indigenous girl and a Black man in bondage, and the Hôtel-Dieu in Montréal which owned four female slaves: three Indigenous and one Black. Montréal’s convent of the Sisters of Notre Dame owned an Indigenous girl and a Black man."90

Indian slaves were also owned by the Sisters of Charity (or "Grey Nuns") which ran Montréal’s Hôpital Général. In fact, "the foundation of the physical support" for this hospital, says Cambridge historian William Foster, was an impressive variety of unfree laborers: female and male convicts, Indian slaves, self-indentured Canadians, and at least 27 British soldiers taken prisoner in the Seven Years’ War.91 Foster shows that the Grey Nuns who ran Montréal’s Hôpital Général "formed the apex of a pyramidal structure of over a hundred individuals, mostly men, in various states of dependency." Besides Indian slaves, the nuns had indentured servants who were "bound ... to the community for a specific term of service." They also had servants called donnés who "obligated themselves legally to serve the Grey Sisters in perpetuity." The donnés, mostly men, were "not free to leave" and were the nuns’ "movable property." English prisoners of war, "held against their will," were bought and sold for a profit. These working inmates were "as unfree as any slave on the sister’s property."92 The Grey Nuns also "imprisoned young women of questionable virtue," held them "confined in cells" "designed for the purpose of correction" and forced them into a "harsh" and "exhausting schedule of domestic work." When the Intendant of New France, François Bigot, tried unsuccessfully to close down the Grey Nuns’ hospital in 1750, he cited complaints from their female inmates.93 The Grey Nuns was founded and led by Marguerite d’Youville. She has been revered as a saint by the Catholic church since 1990. Foster contests her official hagiographies by giving voice to those subordinated to the rigours of captivity by the Grey Nuns. Using historical records, Foster constructs counternarratives to convey the long-silenced stories of slaves held by these nuns. This "community of women," he concludes, "used the redemption and coercion of captives as an instrument to accomplish its earthly purposes."94 As the nuns’ mother superior, d’Youville acquired at least two Indian slaves — a teen and an 11-year old. They were among properties given to the nuns by rich donors in the 1760s. The nuns also had a Sioux slave baptised in 1774.95 For decades, Mother d’Youville owned several slaves of her own, including two Indian women baptised in 1739 and 1766. In addition, she inherited personal slaves from her husband,96 François, after his death in 1730. A notarised list of his personal effects ended with these two pieces of property: "Panis by birth, around ten or eleven years old, value about 150 livres. A second-calf cow, red undercoat, value about thirty livres."97 Marguerite inherited three panis from her husband’s estate, who Foster says had probably "been under her direction for some time." These Indian slaves were "an eleven year old boy name Pierre, a Patoca male also called Pierre and another slave unnamed in the records."98 On at least two occasions, Marguerite d’Youville fought in court to gain ownership of a slave. Trudel says her stepfather, Timothy Sullivan, "accused her in court of having seized" an Indian "slave from him during the night."99 Although Trudel says the outcome of this case was not recorded, the story continues in another case. Foster reveals how, when Sullivan died in 1738, Marguerite was set to inherit his panis. But Sullivan’s Indian slave wanted to stay with Marguerite’s mother and contested the transfer of his ownership to Marguerite. Upon defeating his court challenge, d’Youville "took possession of the audacious slave on the spot."100 Timothy Sullivan (a.k.a. Timothée Silvain) was a violent Irish con man and quack doctor who used fake credentials to pretend that he was of noble stock. Even the Intendant of New France, Gilles Hocquart, said Sullivan was "a charlatan that all sensible people ... have abandoned" and "in whom no one has confidence."101 Marguerite’s husband, François, was another slave-owning scoundrel. Hagiographic accounts regularly note that François peddled furs and alcohol. For example, the Jesuits of Winnipeg, in their 2016 "Saint of the Week" biography of Marguerite, call François "a fur trader and bootlegger who sold liquor illegally to indigenous people."102 Such narratives fail to note his involvement — and hers — in the more despicable business of slavery. Foster called François "a trader in captured slaves" and "a man plying the slave trade." While François was "officially a furrier," Foster said he "made his living as a dealer in illicit liquor and occasionally slaves along the exchange routes running from the Saint Lawrence to the upper Great Lakes."103 François came into the alcohol, fur and slave trades through his father Pierre You Youville. As a soldier, fur trader and voyageur, Pierre was with Robert Cavalier de La Salle when he "discovered" the Mississippi, claimed its entire watershed for France, and named Louisiana for Louis XIV.104 Marguerite had even closer links to the slave/fur trade because she "belonged to one of the great families of New France." Her mother’s father was Governor of Trois-Rivières, René Gaultier de Varennes. His son, Marguerite’s uncle, was none other than the infamous Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye!105 While two of her brothers were priests, Marguerite’s little brother, Christophe, took up the family fur-trade business and was La Vérendrye’s "second in command" during expeditions beyond Lake Superior in the 1730s.106 Marguerite’s father Christophe, a squire and lieutenant,107 owned a female panise from the Great Lakes region who was born around 1706. After Christophe died in 1708, ownership of this slave passed to Marguerite’s mother. This panise, who remained enslaved for her entire life, died at age 30.108 When John Paul II canonised her in 1990, she became the first Canadian-born female saint. Besides her supposed "miracle" cure of a leukemia patient, Marguerite’s main claim to fame was founding the Grey Nuns. Beginning operations with Montréal’s Hôpital Général, they became one of Canada’s largest teaching and nursing orders.109 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission states that although the Grey Nuns had no credentials qualifying them as teachers,110 they were a dominant force within Catholic-run Indian residential schools across Canada from the 1840s on.111 For 150 years, these nuns were on the frontline in the genocidal mission to Christianise, Canadianise and "civilise" tens of thousands of Indigenous children whose ties to family, community and culture were tragically broken. This haunting legacy of the Grey Nuns still lives on in a nation held captive and coerced by the self-deceptive myths of "Canadian values" like devotion to multiculturalism, justice, freedom and human rights. The Laws of Ownership: Trudel presents the slave-owning Catholic clergy and religious orders of New France as but one segment of a whole society where human bondage was the norm. (See "Who were the Slave Owners of New France?" p.35.) Other social groups — government officials, merchants, military officers and fur traders — did own more slaves than those religious professionals were servants of the Church. While noting that "[b]ishops, priests, nuns and members of religious communities ... owned a hundred slaves," Trudel called this "a relatively small number." But what is important, he remarked, is "not the overall numbers of slaves but the fact that religious owned slaves at all."112 While Trudel saw church officials as a distinct social group that owned relatively few slaves, he saw this complicity as inevitable. The church, he suggested, was merely going along with a social system created by others: In a society where slavery was sanctioned by law, practiced by the most prominent people, and widely accepted as a social fact, we do not see why the clergy would have acted differently from the rest of society: the Church, after all, had the same property rights.113 (Emphasis added.) But the Catholic clergy was not separate from "the rest of society" and did not follow the lead of others. Catholicism was the colony’s central organising force. In fact, it dominated almost all aspects of life throughout the French empire, including the laws governing slave owners and their "property rights." The Church was leading, not following, the masses. Slavery in the French empire was governed by the Code Noir (1685). Issued by King Louis XIV, this law regulated enslavement in the West Indies. No specific Code was issued to deal with slavery in the northern reaches of New France. If such a law had existed, said Trudel, it would more appropriately have been called "Code Rouge since Amerindian slaves (called ‘rouges’ or redskins) outnumbered black slaves." Although slave owners in what became Canada had no law governing slavery, they "generally complied with provisions of the Code Noir ... even when not required to do so."114 The Code began with the king declaring that he reigned "by the grace of God" and "Divine Providence." The law’s purpose, he decreed, was not just "to regulate the status and condition of the slaves" "in our american islands," it was issued to "maintain the discipline" of the Church. The edict’s first eight articles show just how closely Catholicism and slavery were shackled together within a single legal system: 1. "[A]ll the Jews ... [and other] declared enemies of the Christian name" must be "evicted" "or face confiscation of body and property." 2. All slaves must be "baptized and instructed" in the Catholic religion. 3. The "public exercise" of other faiths was forbidden and "offenders" were to be "punished as rebels." 4. Only Catholics could own slaves "on pain of confiscation of negres." 5. Those of "the so-called reformed religion" (i.e. Protestants) were forbidden to "disturb or prevent" Catholics, "even their slaves," from "the free exercise" of their religion, "on pain of exemplary punishment." 6. No one, including slaves, could work on Sundays or Catholic holidays "on pain of fine and discretionary punishment of the masters and confiscation of the ... slaves." 7. Slave markets were forbidden from operating on Sundays or Catholic holidays on pain of fines and the "confiscation of the merchandise." 8. NonCatholics could not marry and children "born of such [invalid] unions" were declared "bastards."115 A second Code Noire, issued by King Louis XV in 1724, regulated slavery in Louisiana. It retained all of the laws regulating strict adherence to the Catholic faith, not only by slaves but their by their masters as well.116 The Mass Captivity of Religion:

This concept of social belonging returns us to the issues of ownership and property rights. Just as religious adherents are said to belong to a faith, their leaders often possess the reciprocal belief that as church authorities they have a duty to control their flocks. In the same way that shepherds own and command their sheep, the church held near absolute dominion over its faithful flock in New France. The idea that the church should rule over those belonging to it has been slow to fade away. For example, in 1938, Pope Pius XI argued that the idea of totalitarian governments was absurd. As he put it, "if there is a totalitarian regime — in fact and by right — it is the regime of the church, because man belongs totally to the church."117 (Emphasis added.) During his reign (1922-1939), this pope worked closely with Mussolini’s fascist regime. The totalitarian systems of the Vatican and the Italian state shared the twin pathologies of anti-communism and antiSemitism. For centuries, Catholicism held almost total control over life in New France, Lower Canada and then Quebec. Citizens, leaders and institutions lived under the powerful sway of religious authorities and their strict doctrines, codes and ideologies. While the whole society was bound together by ties to the church, this cultural bondage did not need to rely on physical constraints such as fences, walls, bars, chains or manacles. (See "Tied by Faith, Bound by Law, and Reliant on ‘The Word,’" p.37.) Nevertheless, the church exerted a form of social control that held individuals, organisations and the government firmly in place. So strong was the bondage of this religious social order that it is not unreasonable to liken the life of this colony’s subjects to the sorry lot of slaves. The colonial subjects most tightly bound by the church were those belonging to religious orders. Among them were such nuns as Catherine de St. Augustin and Marie de l’Incarnation who took vows as "slaves of Mary."118 The former was instrumental in founding the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, while the latter was the mother superior of the first Ursuline Order. Both orders owned slaves.119 The Ursulines, in their fervour to convert "savages," started some of Canada’s first residential schools. "We met many savages when we went ashore," said Marie de l’Incarnation, upon arriving from France in 1639, and they were "amazed when told that we had come to teach their children."120 While the subjects of New France were ritually bound together and to their priests by the liturgy of the mass, the captivating beliefs which tied them tightly to Catholicism were imposed at an early age by church control of all formal education. For centuries, the parish clergy and missionaries — including Jesuits, Récollets and Ursulines — provided religious indoctrination as well as basic lessons in arithmetic, history, natural science, reading and writing. The inculcation into Catholic teachings helped ensure the absorption of children into the body of the church by securing their early commitment to the "true faith." Church-run schools were a primary means of ensuring the servility of colonial subjects to religious authorities that dominated social life in New France. Besides controlling all levels of the limited schooling available to colonists, Catholics created the first schools for Indigenous children in what is now Canada. From 1620 to 1680, Catholic boarding schools oversaw the supposed civilisation of savages who were deemed inferior, if not evil. By cutting links between Indian children and their families, communities and cultures, these institutions were seen as the best way to compel obedience to church authorities and doctrines. In short, residential schools were tools of subjugation and assimilation. This put Catholics at the forefront of Canada’s centuries-long, genocidal mission to dominate and destroy Indigenous cultures.

Before the last of these institutions of genocide was finally closed in 1996, more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children had been forced into captivity within Canada’s 139 state-funded residential schools. "Removed from their families and home communities," said the chair of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, "seven generations of aboriginal children were denied their identity through a systematic and concerted effort." The purpose, continued Justice Murray Sinclair, was "to extinguish their culture, language and spirit."121 Besides enforcing genocide and a slavish devotion to religious beliefs, these Christian facilities had another nefarious function. They were part of a Canada-wide scheme to exploit Indigenous children and youth as a valuable source of forced labour. As such, these "schools’ kept Canada’s vile institution of slavery alive and well for 150 more years. While allegedly dedicated to civilising, Christianising and Canadianising inferior cultures, they provided benevolent cover stories to justify and legitimise the genocidal intent of colonial elites. And, by perpetuating the slavery of Indigenous people under the guise of education, these "schools" protected Canada’s duplicitous self-image as a loving force for goodness and Godliness. The institutionalised, nation-building myth that Canada is a Peaceable Kingdom is this country’s most potent and unifying political mass delusion. Functioning as a sacred truth within Canada’s official state religion, this mythology captures adherents within an ideological system akin to cultural slavery. These self-righteous beliefs not only help to bind Canadians together as a fictive nation, they provide an important social-defence mechanism that shields believers from the realisation that in the fervour to help others, Canada has sometimes denigrated and abused them. By examining historic truths about how Canadian churches and the state collaborated to capture, enslave and assimilate Indigenous peoples and others, we may be able to free ourselves from the captivating yet fictive myths that form the cultural foundation of Canada itself. References 1. Afua Cooper, "The Secret of Slavery in Canada," Gender and Women’s Studies in Canada: Critical Terrain, M.H.Hobbs and Carla Rice (eds.), 2013, p.254. http://books.google.ca/books?id=t5PlT9B4CM0C 2. Ibid., p.255. 3. Afua Cooper, The Hanging of Angélique: The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery & the Burning of Old Montréal, 2006, p.8. 4. Cooper 2013, ibid. 5. George Elliott Clarke, "Foreword," in Cooper 2006, p.xii. 6. Ibid. 7. Abigail Bakan, "Reconsidering the Underground Railroad: Slavery & Racialization in the Making of the Canadian State," Socialist Studies, Spring 2008, p.4. 8. Ibid. 9. Katherine McKittrick, "Freedom is a Secret: The Future Usability of the Underground," Black Geographies and the Politics of Place, 2007. pp.98-99. http://mbones.tumblr.com/post/1516478634 10. Cooper 2006, op. cit., p.69. 11. Allen P.Stouffer, Light of Nature and the Law of God: Antislavery in Ontario, 1833-1877, 1992. http://books.google.ca/books?id=B7fs9Dv3hS0C 12. Constance Backhouse, Colour-coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950, 1999. http://books.google.ca/books?id=BZlsTAH7GWIC 13. Jill Vickers, The Politics of Race: Canada, Australia, the U.S., 2002, p.73. http://books.google.ca/books?id=AzQq-yiZ3k0C 14. Abolition of slavery timeline 15. Cooper 2013, op. cit., p.264. 16. Marcel Trudel, Canada’s Forgotten Slaves: Two Hundred Years of Bondage, 2013, p.254. 17. Ibid., p.268. 18. Ibid., p.103. 19. Ibid., pp.268-269. 20. Ibid., p.103. 21. Ibid., pp.111-112. 22. Ibid., p.269. 23. Ibid., back cover. 24. Ibid., pp.270-271. 25. Ibid., pp.266-267. 26. Ibid., p.260. 27. Ibid., p.63. 28. Ibid., p.136. 29. Ibid., p.57. 30. William R. Riddell, "The Slave in Canada," The Journal of Negro History, July 1920, Vol.V, No.3, p.268. 31. Trudel, op. cit., p.76. 32. In Brett Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic Slaveries in New France, 2012, p.395. 33. Trudel, op. cit., p.70. 34. Ibid., p.78. 35. Brett Rushforth, "The Origins of Indian Slavery in New France," The William & Mary Quarterly, Oct.2003, pp.802, 777. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3491699 36. Trudel, ibid., p.84. 37. Ibid., p.27. 38. Ibid., pp.107-108. 39. Ibid., p.117. 40. Ibid., p.76. 41. Rushforth, op. cit., p.793. 42. Ibid., p.798. 43. Ibid., p.799 . 44. Three Years Travels through the Interior Parts of North America, 1798, p.177. In Rushforth, op. cit., p. 808. 45. Ibid. 46. Karlee Sapoznik, "Where the Historiography Falls Short: La Vérendrye through the Lens of Gender, Race and Slavery in Early French Canada, 1731-1749," Manitoba History, Winter 2009. 47. Trudel, op. cit., p.108. 48. Yves F. Zoltvany, "Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye, Pierre," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1974. 49. Ibid. 50. Denis Combet, "La Vérendrye: Archetypal Ideal of the Voyageur." 51. Pure Gold Coin – Great Canadian Explorers Series: Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye 52. Zoltvany, op. cit. 53. Trudel, op. cit., p.58. 54. Fur Trade, Canadian Encyclopedia Economic Activities: Fur Trade, History Museum Tangi Villerbu, "French-Canadian Trappers of the American Plains & Rockies." 55. Black Enslavement in Canada. 56. Population: Slavery, History Museum 57. Key word search within this source 58. Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye, Canadian Encyclopedia The Explorers: Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye, History Museum Combet, op. cit. 59. Zoltvany, op. cit. 60. Keyword search of the AFN website 61. What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation, 2015, p.15. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future, 2015, p.47. http://books.google.ca/books?id=-rA9CgAAQBAJ 62. Honourary Witness, Robert Waisman, Jewish Holocaust Survivor, p.331 63. Honouring the... Op. cit., pp.193-194. 64. "Extract of a letter addressed by Louis XIV to Monsieur de la Barre, July 21, 1684," The Documentary History of the State of New-York, Vol.1, E.B. O’Callaghan (ed.), 1850, p.72. http://books.google.ca/books?id=nEtSAAAAcAAJ 65. Ibid., p.73 66. W.H. Lewis, The Splendid Century: Life in the France of Louis XIV, 1957, p.214. 67. "Memoir of the Marquis of Seignelay," O’Callaghan, op. cit., pp.320-321. http://books.google.ca/books?id=rixTAAAAcAAJ 68. Ibid., p.321. 69. "Extracts from a Memoir of the King," Versailles, Mar. 30, 1687, O’Callaghan, op. cit., p.322. 70. C.J.Jaenen, "Lamberville, Jean de," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1969. 71. "Extracts from a Memoir..." ibid. 72. Daniel P. Barr, Unconquered: The Iroquois League at War in Colonial America, 2006, p.87. http://books.google.ca/books?id=vi1ROx0PmI4C 73. Francis Parkman, France and England in North America, Part 5, Count Frontenac and New France under Louis XIV, 1877, p.138. 74. Barbara Alice Mann, Native American Speakers of the Eastern Woodlands: Selected Speeches and Critical Analyses, 2001, p.44. 75. Parkman, op. cit., p.141. 76. Ibid., pp.139, 142 77. Ibid., p.139. 78. Jean Baptiste de La Croix de Chevriers De Saint-Valier, Estat present de l’Eglise et de la Colonie Françoise dans la Nouvelle France, 1856, pp.91-92. http://books.google.ca/books?id=OTlfAAAAcAAJ 79. Trudel, op. cit., pp.27, 112. 80. Alfred Rambaud, "Jean-Baptiste de La Croix de Chevrières de St-Vallier," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1969. 81. Daniel K. Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization, 1992, p.158. 82. Ibid., pp.159-160. 83. Eric Chase, The Brief Origins of May Day, 1993. 84. John Burdick, "Catholic Church in Latin America and the Caribbean," Africana: Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Anthony Appiah and Henry Gates, Jr. (eds.), 2004, p.772. 85. Trudel, op. cit., pp.104, 269 86. See separate entries for these bishops in Dictionary of Canadian Biography 87. Trudel, op. cit., pp.112-113. 88. Ibid., pp.112-113, 115. 89. Ibid., p.117 90. Ibid., pp.114-115. 91. William Henry Foster, The Captors’ Narrative: Catholic Women and Their Puritan Men on the Early American Frontier, 2003, p.91. 92. Ibid., pp.91-100. 93. Ibid., pp.97-98. 94. Foster, op. cit., p.106. 95. Trudel, op. cit., pp.114, 258. 96. Ibid., pp.114-115. 97. Ibid., pp.85-86. 98. Foster, op. cit., p.96. 99. Trudel, op. cit., p.99. 100. Foster, op. cit., p97. 101. Peter Moogk, "Timothy Sullivan," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol.3, 1974. 102. "Saint of the Week," Community of St. Ignatius, Winnipeg, Oct. 16, 2016. 103. Foster, op. cit., p.95. 104. Person Sheet, Pierre You 105. Claudette Lacelle, "Dufrost de Lajemmerais, Marie-Marguerite," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1979. 106. Antoine Champagne, "Dufrost De La Jemerais, Christophe," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol.2, 1969. 107. Person Sheet, Christophe Dufrost 108. Foster, op. cit., p.76. 109. Canada’s Residential Schools: History, Origins to 1939, Vol.1, 2015, p.90. 110. Ibid., p.96. 111. Ibid., p.89. 112. Trudel, op. cit., p.115. 113. Ibid., pp.111-112. 114. Ibid., p.122. 115. The "Code Noir" (1685) 116. Louisiana’s Code Noir (1724) 117. David Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini: Secret History of Pius XI & the Rise of Fascism in Europe, 2014, p.153. 118. Cornelius John Jaenen, The Relations Between Church and State in New France, 1647-1685, 1962, p.578. 119. Trudel, p.115. 120. Robert Carney, "Aboriginal Residential Schools before Confederation: The Early Experience," Historical Studies (Canada), 61, 1995, p.13. 121. Canada’s Residential..., op. cit., p.vii. |

|

The

above article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017),

magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT). The

above article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017),

magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this coupon, or use the paypal link on COAT's webpage. Subscription prices within Canada: three issues ($25), six issues ($45). If quoting this article, please cite the source and COAT's website. Thanks! |

|

You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion! You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion!

Captive Canada: This issue (#68) deals with (a) the WWI-era mass internment of Ukrainian Canadians (1914-1920), (b) this community's split between leftists and ultra right nationalists and (c) the mainstream racism and xenophobia of so-called progressive "Social Gospellers" (such as the CCF's Rev.J.S. Woodsworth) who were so captivated by their religious and political beliefs that they helped administer the genocidal Indian residential school program and turned a blind eye to government repression and internment during the mass psychosis of the 20th-century's "Red Scare." (Click here to read this issue online.) Read the introductory article here: |

|

In

whiting out this shameful history, Canadians like to contrast themselves with

Americans. "[W]e associate the word ‘slavery’ with the United States," says

Cooper, "not Canada."4

In

whiting out this shameful history, Canadians like to contrast themselves with

Americans. "[W]e associate the word ‘slavery’ with the United States," says

Cooper, "not Canada."4 Erasing

Slavery from Public Memory

Erasing

Slavery from Public Memory La

Vérendrye:

La

Vérendrye:

The

Slaves of St. Marguerite

The

Slaves of St. Marguerite While

Trudel saw the church as one small slave-owning segment of society in New

France, the fact is that — by law — all of this colony’s slaves and slave

masters had to be Catholic. Whether they were politicians, military officers,

professionals, tradespeople or religious leaders, all slave owners belonged

to the Catholic Church.

While

Trudel saw the church as one small slave-owning segment of society in New

France, the fact is that — by law — all of this colony’s slaves and slave

masters had to be Catholic. Whether they were politicians, military officers,

professionals, tradespeople or religious leaders, all slave owners belonged

to the Catholic Church.  In

the early 1830s, just as slavery was officially outlawed throughout the British

empire, Indian residential schools sprang up and were spread like a cultural

disease across the Canadian colonies. Catholic and Protestant churches alike

spawned these facilities in order to supposedly "uplift" Indigenous people with

the advanced moral traditions and work habits of Canada’s mainstream society.

While the United Church and its Methodist and Presbyterian forebears operated a

tenth of Canada’s Indian residential schools, the Anglicans ran 30 percent, and

60 percent were under Catholic control.

In

the early 1830s, just as slavery was officially outlawed throughout the British

empire, Indian residential schools sprang up and were spread like a cultural

disease across the Canadian colonies. Catholic and Protestant churches alike

spawned these facilities in order to supposedly "uplift" Indigenous people with

the advanced moral traditions and work habits of Canada’s mainstream society.

While the United Church and its Methodist and Presbyterian forebears operated a

tenth of Canada’s Indian residential schools, the Anglicans ran 30 percent, and

60 percent were under Catholic control.