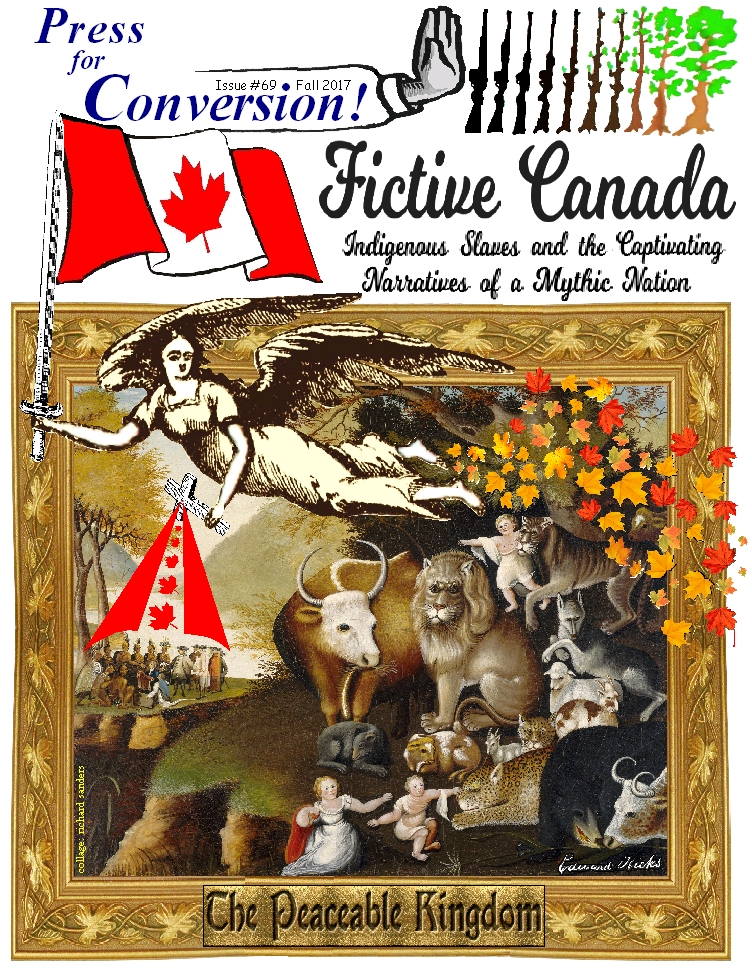

Fictive Canada:

Issue #69,

Press for Conversion! (Fall 2017)

Click here for info about

symbolism of the front cover collage |

|

|

Table of Contents 1-

True Crime Stories and the

2-

John Cabot & Britain’s Fictitious Claim on

Canada: > Why “The Dominion of Canada”?

3-

Canada’s Extraordinary Redactions:

4-

Textbook Cases of Canadian Racism:

5-

From Popes and Pirates to Politicians and

Pioneers: >

The Canadian Legal Fiction of

6-

Breaking the Bonds of Ignorance and Denial:

>

Oh say can you see? Blindsport

for Peaceable Racism

7-

Native

Captivity and Slave Labour 8-

Child Slavery in Canada’s

>

Jean L’Heureux:

|

Canada’s Extraordinary Redactions: Held Captive by Nation-Building

View this article from

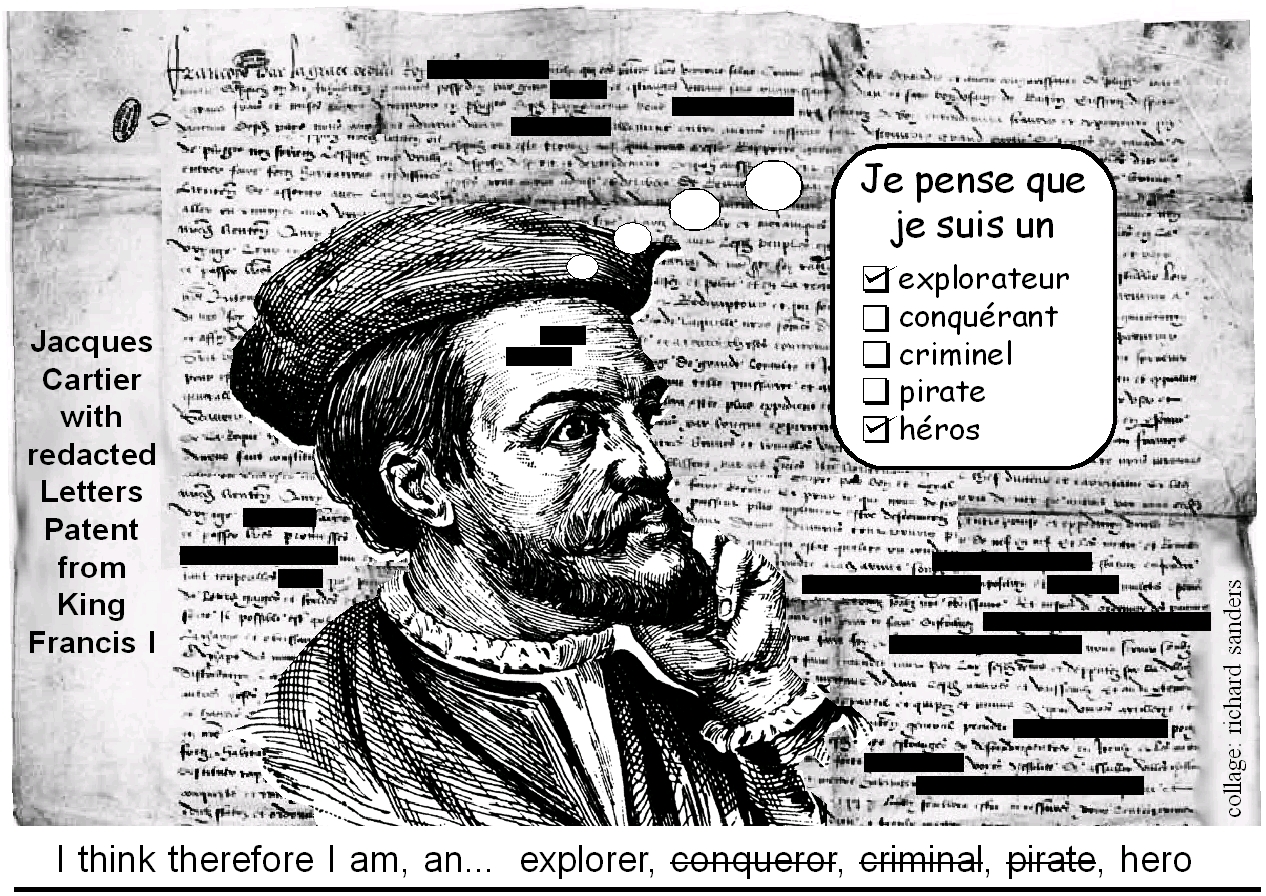

Fictive Canada (pp.8-14) in PDF format Besides John Cabot, another towering figure in the pantheon of Canada’s national heroes, long said to have "discovered" this land, is Jacques Cartier. Both Cabot and Cartier were little more than officially aggrandized criminals — well-armed pirates charting the way for European kings and popes to seize control of what became known as "Canada." While Cabot staked the English monarchy’s fictive claim to dominate North America, Cartier is celebrated for three voyages, between 1534 and 1542, which set the colonial course of history for New France. As anthropologist Bruce Trigger noted in 1985, the era of European explorations following Cabot and Cartier, until "the establishment of royal government in New France in 1663 was long seen as a ‘Heroic Age.’" The brave heroes in question were French explorers, missionaries, and settlers [who] performed noble deeds. Cartier the ‘discoverer’ of the St. Lawrence Valley, was hailed as the prototype of a bold mariner.1 In his book The Hero and the Historians: Historiography and the Uses of Jacques Cartier (2010), Alan Gordon documents an ebb and flow in the centuries-long manipulation of Cartier’s image by a diverse array of professionals with special interests. Gordon delves into how historians have exploited the Cartier brand, and discusses how politicians, bureaucrats, government agencies, church leaders, non-profit groups and tourism businesses have all profited from fictive narratives that capitalise on the glorious myths still floating around Cartier. In the early 1800s, narratives about Cartier were used to serve the political aspirations of Quebec nationalists. By "inventing Cartier as a national historical hero," says Gordon, "nineteenth-century French Canadians were also inventing an identity for themselves." During the latter half of 19th century, there was a "sudden and massive outpouring of representations of Jacques Cartier" which Gordon dubs "Cartiermania." While the "creators" and "guardians" of this "Cartier cult … sprang from the ranks of Quebec’s middle-class nationalist intellectuals," says Gordon, its "broad embrace suggests that it resonated with ordinary people."2 |

|

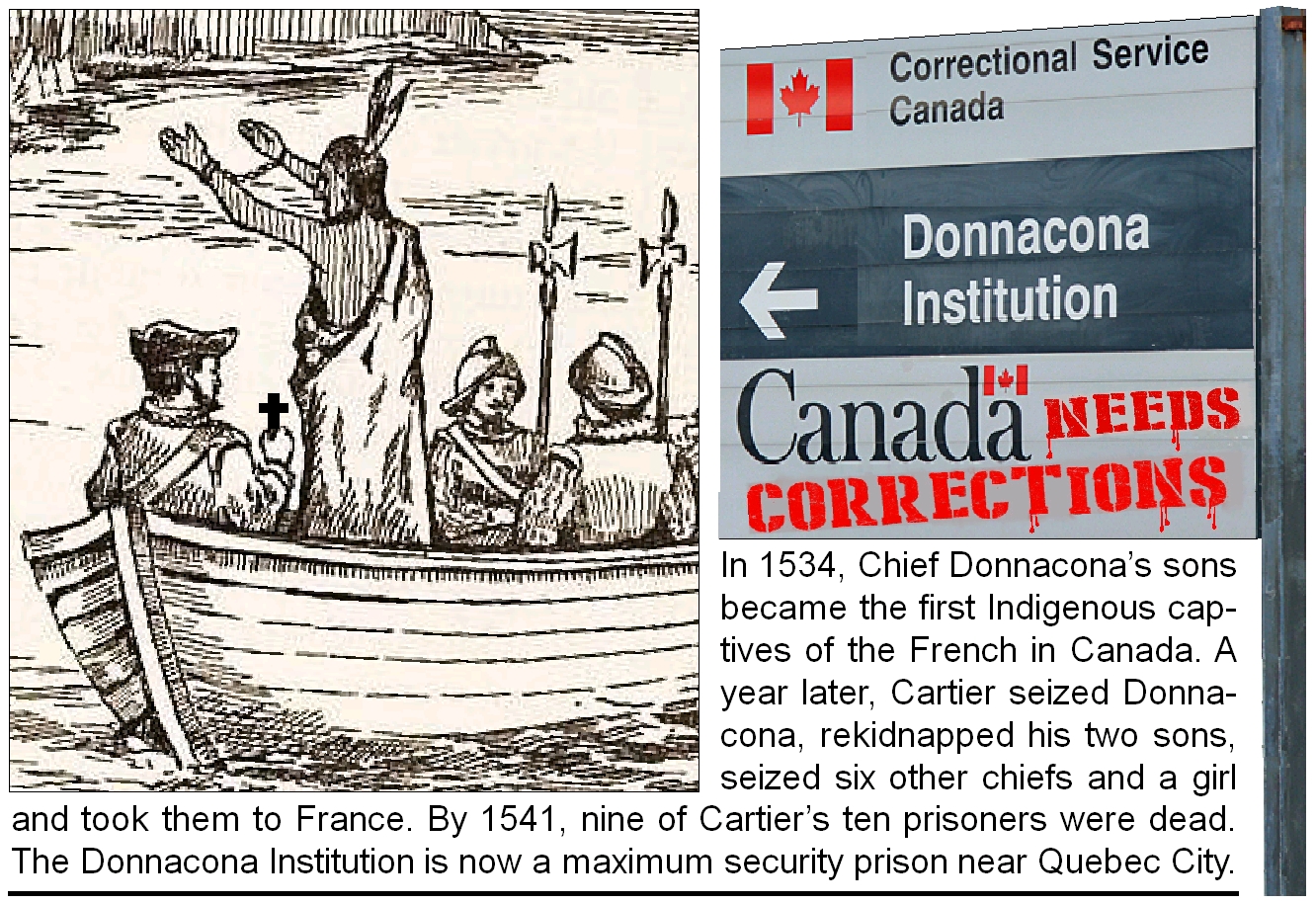

The post-colonial era was a time when Cartier’s image has put to use by Anglophone elites, academic and otherwise, eager to promote English-dominated Canadian nationalism. Gordon describes how the federal government in "Ottawa attempted to elevate Cartier into a national bicultural symbol."3 And, in describing this era of historiography, Trigger notes that Many English Canadian historians sought to promote national unity by urging their readers to honour the brave men and women of that period [the so-called ‘Heroic Age’] as the founders not only of New France but of modern Canada as well.4 Champlain and Jesuit missionaries were "lauded" by English-speaking historians, says Trigger, "as stalwart men who sacrificed their lives to prevent New France from being overrun by savages." In so doing, he says, they provided a model of heroic deeds in which later generations of Canadians, regardless of their ethnic origins, mother tongue, or religious creed, can take particular pride. The heroes of New France were venerated "in true Victorian fashion" with "voluminous publications,…poems, paintings, … sculptures," plaques, statues and shrines, and "impressed on the minds of children in … history texts."5 Gordon explains that by the 1930s, "government agencies, both federal and provincial, were also drawn to adopt Cartier as a symbol of (often competing) national identities." Then, during the 1960s, "with the emerging Québécois nationalism characteristic of the Quiet Revolution," the "old common sense surrounding Cartier no longer fit." Since then, says Gordon, Cartier’s celebrity has receded, "not into obscurity but to the periphery."6 What’s in a Name? The Cartier myth remains alive and well in Canada. A variety of Canadian governmental and non-governmental sources still promote highly sanitized renditions of his legacy. For example, while mainstream narratives often remember Cartier as a key figure in the story of how Canada got its name, they often remove from the record any mention whatsoever of Cartier’s role in the kidnapping, extended captivity and enslavement of Aboriginal people. While noting that Cartier "is usually credited with discovering Canada," the Canadian Encyclopedia tells us that Cartier "was the first explorer of the Gulf of St Lawrence." By declaring that Cartier "discovered one of the world’s great rivers,"7 this popular mainstream source continues the longstanding tradition of collective Canadian ignorance and amnesia. The myth that Cartier "discovered" the St. Lawrence, turns a blind eye to the fact that the river had already been well explored by countless generations of native peoples who had been occupying the region for many thousands of years. In July 1534, upon making landfall, possibly near Gaspé, Cartier erected a 30-foot cross with a "fleur-de-luce"-emblazoned shield and the words "Vive le Roi de France." With this symbolic magic, Cartier laid claim to the land for France, while reserving its inhabitants’ souls for Catholicism. An 1865 history textbook called A School History of Canada this giant cross with its royal inscription was emblematic of the new sovereignty of France in America. Thus was accomplished a most memorable event; and thus was Canada silently and unconsciously incorporated into a mighty empire. This rendition, in a section called "Cartier’s Discovery of Canada," then states that the cross raising "completed that three-fold act of discovery in America," which "placed ... on a vast unknown continent, the symbols of the sovereignty of three of the greatest nations of Europe." Spain, England and France, this history text said, planted each their foot upon the virgin soil of a new world, eager to develop upon a broad and open field the industry and enterprise of their separate nationalities. Cartier’s symbolic capture of Canada for France was recorded in the first extant narrative of the event, which historians such as Ramsay Cook believe is "probably based on a ship’s log … by the captain, Cartier, himself."8 In this original version — The Voyages of Jacques Cartier — the giant cross and royal shield were raised "in the presence of" many members of a "great multitude of wild men." Remarkably, these 200 "men, women and children," in about 40 boats,9 had journeyed 700 kilometres from the town of Stadacona, where Quebec City now stands. Cartier’s account says the Stadaconan chief, Donnacona, "made us a long harangue … that we ought not to have set up this cross without his permission." Cartier then described the trickery he used to lure Donnacona and his sons close enough to forcibly render them captive on his ship: [W]hen he finished his harangue, we held up an axe to him, pretending we would barter it …. and little by little [he] drew near the side of our vessel.10 One of our fellows, ... in our boat, took hold on theirs and suddenly leapt into it, with two or three more, who enforced them to enter into our ships.11 After Cartier had "entertained them very freely, making them eat and drink" (likely alcohol), they were bribed with trinkets. Cartier then told Donnacona that "we would take two of his children with us." The chief’s two sons, who Cartier says "we had detained to take with us,"12 were rendered captive and taken away from their family, community and country to France. Throughout Canadian history, popular sources of fiction such as history textbooks and encyclopedia’s have either removed all reference to Cartier’s kidnapping of Indigenous peoples, or excused these crimes with the rationales that commonly afflicted Eurocentric racists. (See "Canadian History Books as Captivating Works of Fiction," p.15.) During his second visit to "Canada," Cartier exploited Donnacona’s sons as translators and guides. His journal refers to them as "the two savages we had captured on our first voyage" and the "two men we had seized on our former voyage."14 Cartier had also used his captives as objects of curiosity in France, where they met an untimely death five years later. There are, of course, gravely conflicting renditions of these pivotal events in Canadian history. The Canadian Encyclopedia whitewashes the rendition of these two young men by telling us that in 1534, after "planting a cross and engaging in some trading and negotiations, Cartier’s ships left … with two of the Iroquois chief Donnacona’s sons and returned to France."15 This popular source also claims that the chief "agreed to let his sons Domagaya and Taignoagy return with Cartier to France."16 This shameless version strikes from history that the original record of Cartier’s voyages used the words "seized," "captured" and "detained" to describe the deception and force used to "take" the brothers from their father in 1534. This leading Canadian encyclopedia also ignores the obvious fact that once his sons’ kidnapping was a fait accompli, Donnacona had no real choice when he is said to have "agreed" to their captivity. The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery is blunt but accurate in assessing this key incident. It says French enslavement of Native Americans began in 1534 when Jacques Cartier seized several Native Americans on his first expedition to the New World and carried two to France.17

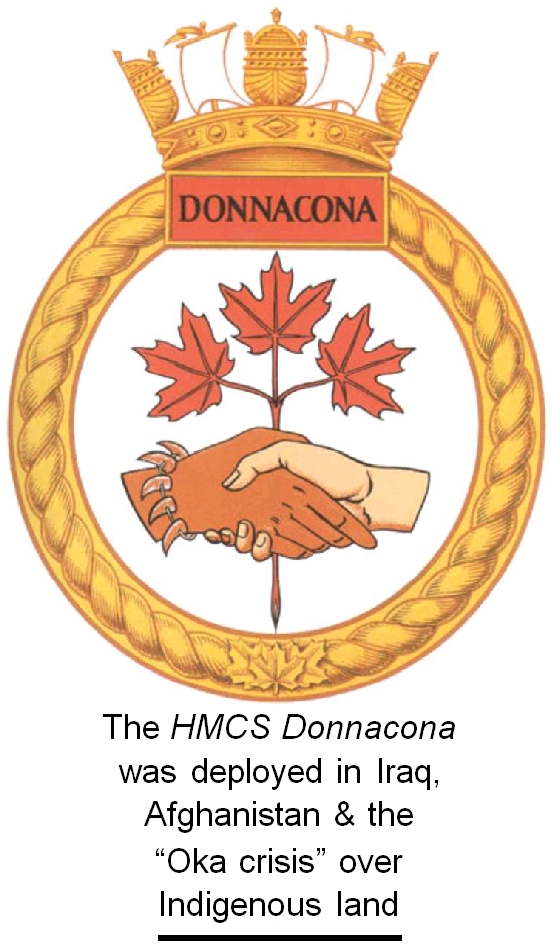

In 1535, two Indian Youths told Jacques Cartier about the route to ‘kanata.’ They were referring to the village of Stadacona; ‘kanata’ was simply the Huron-Iroquois word for ‘village’ or ‘settlement.’ But for want of another name, Cartier used ‘Canada’ to refer not only to Stadacona…, but also to the entire area subject to its chief, Donnacona.18 This innocent-sounding Heritage-Canada tale appears verbatim on other government websites, including those celebrating Quebec’s 400th anniversary (2008)19 and Canada’s 150th (2017).20 Left unsaid in these sanitized renditions is the fact that the story’s "two Indian Youths" were actually Donnacona’s kidnapped sons whom Cartier had by then been holding captive for more than a year. Parks Canada (PC) has also helped shield Canadians from the embarrassing fact that Donnacona’s sons were kidnapped. Stating that "in 1534, Jacques Cartier encountered several Amerindians near the present-day city of Gaspé," the PC story says Cartier "returned to France with two young members of this group."21 The PC staff responsible for such redactions of history should read their own "Code of Ethics." It says that "All Parks Canada employees must be open and honest in their dealings with the public, stake-holders and other organizations." It also states that PC "employees contribute in a fundamental way to good government, to democracy and to Canadian society."22 In 1535, during his second visit, Cartier set another powerful example for future Canadians by using deception and force to seize even more Indians as hostages. This second case of kidnapping was also preceded by the raising of a huge crucifix. The 35-foot cross featured a shield with France’s coat of arms, and words proclaiming the sovereignty of King Francis. Cartier’s own diary says he lured Donnacona and others into captivity. After enticing them to "eat and drink as usual," Cartier used what he called a "pretty prank … to take their lord Dounacona, Taignoagny, Domagaia, and some more of the chiefest of them prisoners ... to bring them into France."23 When Donnacona and the other chiefs were seized, the "Canadians ... began to flee and scamper off like sheep before wolves."24 Cartier’s journal notes how, after his troops "laid up the prisoners under good guard and safety," the Stadaconans lined the shore "striking their breasts, and crying and howling like wolves" through the night.25 Canada’s First Lies and First Prisoners By 1541, when Cartier made his third and last trip to "Canada," nine of his ten Indigenous prisoners, excepting one young girl, had died in France. While he admitted to the Stadaconans that chief Donnacona was dead, Cartier lied about the sorry fate of the others he had kidnapped, saying they were all married and living in France "as great Lords."26 Like Cartier, who lied to cover up the deaths of his prisoners, Canada’s government continues — 500 years later — to deceive citizens by redacting Cartier’s crimes from official narratives. For example, in a camouflaged tale of how Canada got its name, the Department of National Defence (DND) avoids the truth saying: When Jacques Cartier returned to France from his first voyage to America, he took back with him two Native braves. They returned to America with Cartier on his second voyage and acted as guides. They told Cartier about the settlements of Stadacona and Hochelaga [site of present-day Montreal] … and referred to them by the Huron-Iroquois word Kenneta, which means ‘a habitation.’27 Although this well-varnished rendition of history quaintly notes "two Native braves" that Cartier "took back with him," it holds Canadians captive with a deceitful story that cleverly excludes all mention of European trickery and violence, or the kidnapping and death of their Indigenous hostages. DND presents this sanitised version on a webpage about the HMCS Donnacona, a Navy Reserve division of 200 sailors in Montreal. Although using the title HMCS ("Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship"), the Donnacona is not a ship, but a land-based naval unit, or so-called "Stone Frigate." It was deployed in the Iraq (1991) and Afghan (2001) wars, in various NATO operations and, quite insultingly, in the Oka crisis over Indigenous land (1990).28

Heraldry, with origins in the formalized symbolic conventions that identified mediaeval knights whose identities were hidden by battle armour, is equally concerned with the fineries of military rank and protocol. As the key representative of Britain’s monarchy, the Governor General is Commander-in-Chief of Canada’s Armed Forces and the highest authority within this country’s heraldic system. The symbolic "badge" of the HMCS Donnacona was confirmed with Letters Patent from the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 2009.30 This occurred just in time for that year’s 475th anniversary festivities heralding Cartier’s landfall in Gaspé, where he kidnapped Donnacona’s sons. Canada’s then Governor General — former CBC journalist Michaëlle Jean — issued a statement saying she was "delighted" to "celebrate" Cartier’s arrival. "What our history books teach us of Cartier’s first expedition in 1534 has become the stuff of legend," she noted. Ironically, she then built upon the deceitful "legend" of Canadian multiculturalism by speaking of Cartier’s "cordial relations with the St. Lawrence Iroquoians." Governor General Jean then continued the coverup of Cartier’s role as kidnapper by saying that he "returned to France with two of Donnacona’s sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny."31 Although noting that "certain aspects of the story are open to interpretation," Jean did not elaborate. Instead, her speech disguised the truth of Cartier’s crimes with a torrent of effusive babble about the "joyful celebrations of culture and the blending of cultures highlighting this historic date for the Gaspé Peninsula and all of Canada …" But the duplicity in rendering a laundered version of Cartier’s crime didn’t end there. Jean had the audacity to conclude this set of lies with a pretentious and hypocritical appeal for honesty! The Cartier "celebrations," she said, "provide us with the opportunity to further our understanding of our history and seek out the truth, two conditions necessary for respect and harmony."32 A few weeks later, Jean had a perfect symbolic opportunity to make a correction to her flawed rendition of the Cartier-Donnacona "legend." The occasion was an awards ceremony in Quebec City, where as Governor General she handed out "Corrections Exemplary Service Medals" to eight employees of a maximum-security prison called ... the Donnacona Institution! This would certainly have been a good moment to mention the injustice of Cartier’s imprisonment of Donnacona, his sons, various chiefs and Indigenous children. Despite her geographic proximity to the 475-year-old crime scene where Donnacona was taken prisoner, Canada’s Governor General did not seize the "opportunity" to correct her obfuscations of this country’s sanitised historical record. To be fair, the fault probably lies with Jean’s speech writers. The Governor General may have had no real idea of the irony in her words and actions. Those enslaved by myths about Canada’s multicultural values, and captivated by the blanched versions of our criminal history, cannot see the shame in a federal prison bearing the name of Chief Donnacona, whose sons were the first known "Canadian" prisoners. And who better to put a trustworthy face on Canada’s history of racist captivity than Jean, a former CBC personality descended from slaves in Haiti, another former French colony? Further irony regarding this ignorance about Canada’s criminal heroes is that while Jean has 12 honourary PhDs — in everything from philosophy, literature, foreign relations and military science — five of her doctorates are in law.33 The breathtaking abandon with which high-ranking government officials turn a blind eye to basic facts of Canada’s criminal history is, unfortunately, just the tip of the cultural iceberg. The longstanding truth of Canada’s whole legal system is that "First Nations" are also "First Prisoners." And, like state captives unceremoniously thrown into solitary confinement, the long Canadian tradition of imprisoning Indigenous peoples has been thrown down the nation’s memory hole. Once this history is secured out of sight and mind behind the prison-like walls of cultural amnesia, it is difficult to release it to the light of day. Successive governments and civil-society groups have aided and abetted the cleansing of historical memory — not only of the extraordinary renditions of Donnacona’s time, but of the many thousands of Indigenous prisoners and slaves who have been held by Europeans during the succeeding five centuries. The struggle to correct false renditions of history, and to redress the legacy of Canada’s crimes, is ongoing. Imperial Motives, Criminal Precedents and Religious Excuses Cartier’s brazen use of deception and armed force to capture Aboriginal "Canadian" captives exemplifies his legacy as a paragon of criminality who brought Europe’s culture of imperialism to North America. As one of Canada’s founding criminals, Cartier’s actions set powerful legal and political precedents for the evolution of our "Peaceable Kingdom." Cartier journals contain confessions of imperial crimes which reveal the motives behind them, the means used to commit them, and the benevolent alibis used in their justification. In March 1533, when Francis I gave permission and funding for Cartier’s initial voyage, he launched France’s overseas empire. Cartier’s royal contract stated the king’s intent that Cartier "discover certain islands and countries where it is said that a great abundance of gold and other precious things is to be found."34 Cartier’s greed for material wealth is clear from the narrative of his second voyage, which admits his decision to "outwit" the Stadaconans and "seize their leader." Cartier’s diary says he decided "to take Donnacona to France" because he wanted the chief to tell King Francis that "there are immense quantities of gold, rubies, and other rich things" in "Canada."35 The ploy worked. In 1539, a navigator named Joao Lagarto reported to his monarch, John III of Portugal, that "the King of France says the Indian King [Donnacona] told him there … are many mines of gold and silver in great abundance …"36 Two years later, when describing the French armed forces being assembled for Cartier’s third expedition, a Spanish spy wrote, "When the members of the said army have arrived on land, they will search for gold and silver mines."37 Cartier’s account of that voyage noted that his captives told "the King that there were great riches"38 in Canada. With this in mind, the King’s contract for the third voyage spelled out a formula for dividing the spoils that were expected from the conquest. The King’s new license said one "third of all the movable gains and profits proceeding from the said voyage, army, and expedition," were to be divided among those who took part. This including Cartier, who was the fleet’s admiral and chief navigator. Another third, said the King, "We have reserved ... for Ourself."39 The final portion was for the King’s friend and fellow nobleman, Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval, a pirate and professional soldier who became the first Lieutenant General in France’s first colony.40 Although the French king had been informed of the "abundance of good fish" and "[a]nimals whose hides as leather are worth ten cruzados each," he was also told fanciful myths about "Canada." For example, Lagarto says Donnacona told the French king that "Canada" had an "abundance of clove, nutmeg, and pepper," as well as "oranges and pomegranates." If Donnacona did tell Francis these tall tales, he was perhaps lying in order to expedite his return home as a valuable guide to these false riches. Fabrications about gold, silver and spices were also apparently fleshed out in Donnacona’s phantasmagorical accounts of people "possessing no anus" who "never eat nor digest," and others with "only one leg," as well as "men who fly, having wings on their arms like bats."41 Like the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs whose slave traders were spreading their mercantile tentacles around the world, King Francis would have been interested in finding profitable sources of able-bodied people. During his first voyage, in which he described Labrador as "the land God gave to Cain," Cartier reported that "[t]here are people on this coast whose bodies are fairly well formed, but they are a wild and savage folk."42 In describing the wealth of "Canada," Cartier often combined his accounts of physical riches with accounts of human resources, which added potential for acquiring religious converts. For example, in introducing his second voyage, Cartier told the king "you will learn and hear of their fertility and richness, of the immense numbers of peoples living there…." Cartier then assured the monarch that he and his men were filled "with the sure hope of the future increase of our most holy faith and of your possessions …"43 In the commission for Cartier’s third voyage, the King similarly mixed up references to material "commodities" with mention of "peoples," captives and religious converts. He noted, for instance, that "the lands of Canada and Hochelaga" are provided with several valuable commodities and the peoples of those countries [are] well formed of body and limb and well endowed in mind and understanding of whom he [Cartier] brought back at the same time a certain number whom We have had kept for a long time and instructed in our said holy faith.44 This is similar to a passage in Columbus’ 1492 journal which told Spain’s monarchs about the physical and mental qualities of "Indians" and remarks on their capture, conversion and commodification as "servants": "They are all of a good size and stature, and handsomely formed …. It appears to me, that the people are ingenious, and would be good servants and I am of opinion that they would very readily become Christians …. If it please our Lord, I intend ... to carry home six of them to your Highnesses, that they may learn our language."45 Seizing Indigenous captives served the imperial intent of early conquerors like Columbus and Cartier. Besides using them as objects of curiosity in Europe’s royal courts, and to attest to the richness of newly "discovered" lands, native hostages could be urged to inspire royal funding for follow-up expeditions on which they were exploited as guides and translators. And, imperial purposes were also served by having a few initial native hostages convert to Christianity. Upon their return, these early religious captives helped spread Europe’s invasive culture amongst the enemy population. King Francis noted that Cartier brought to Us from those countries various men whom We have kept for a long time in our kingdom having them instructed in the love and fear of God and of His holy law and Christian doctrine in the intention of having them taken back to the said countries, …in order more easily to lead the other peoples of those countries to believe in our holy faith.46 (Emphasis added.)

"Divide and Conquer" with Hate Speech and other Weapons Christianity provided linguistic tools to pen people into opposing groups, namely, the Divine and the Demonic. This is illustrated in a 1538 list of "men and supplies … that the King wished to send to Canada" for Cartier’s third voyage. The "great King Francis" was said to be full of "piety, magnanimity, and open-heartedness" because, "notwithstanding that wars had exhausted his finances," was "in a state of peace" and wanted "to establish the Christian Religion in a country of Savages at the other end of the world."47 His goal was said to be the "winning over of an infinite number of souls to God" to gain "their liberation from the domination and tyranny of the infernal Demon, to whom they used to sacrifice even their own Children."48 This apocryphal language of demonisation, with its bogus accusations of child sacrifice, typified the witch hunts then rife in Europe, where the Catholic monopoly on truth was being challenged. But what Cartier called "winning over … souls to God" from "the infernal Demon" required more than just official, hate literature. Religious laws had to be enforced by state-sanctioned acts of ultraviolence. Cartier’s support for the imposition of religious superiority using state sanctioned violence, including execution, is found in his account of the second voyage to Canada (1535-1536). This may be the first document about "Canada" to incite hatred against identifiable groups and to support their execution. Telling Francis I that "we have seen this most holy faith of ours in the struggle against wicked heretics and false law-makers," Cartier dotingly congratulated the king for all "the good regulations and orders you have instituted throughout your territories and kingdom." Bluntly described the enemies of Catholicism as "wicked Lutherans, apostates, and imitators of Mahomet," Cartier applauded the use of "capital punishment" against these "infants of Satan."49 Fresh in Cartier’s mind when penning this fanatical invective may have been the "Affair of the Placards" (1534-1535). During this offensive, hundreds were arrested and dozens burned at the stake for the crime of putting up anti-Catholic posters. The French king’s savage persecution of dissidents culminated in 1545, the same year that Cartier’s second journal was published. That year, Francis launched a crusade against Waldensian "heretics" in southeast France. While about 8,000 of these Protestants were slaughtered, 700 survivors were imprisoned and then sold into slavery aboard French galleys.50 Cartier took good advantage of the king’s willingness to force prisoners into labour aboard French warships. Two documents from October 1540 detail the king’s orders that 50 inmates be provided for Cartier’s third voyage. Cartier was given his choice of "prisoners accused of or charged with any crime whatsoever," except for "crimes of heresy … against God," "lese-majesty" [i.e., offending the king’s dignity] and "counterfeiters."51 While these brands of inmates could not be trusted on Cartier’s mission of imperial conquest and religious conversion in Canada, murderers were welcomed. Cartier also engaged certain "gentlemen" who, like the prisoners, were compelled to join his voyage. According to the Spanish spy who described Cartier’s expedition, these men included "two unfortunates from Brittany who have committed some killing, for which they will do penance on this voyage," and another who "was sentenced to go on this voyage because … he insulted" several aristocrats.52 Besides enlisting prisoners and "gentlemen" guilty of murder and insulting nobles, Cartier’s forces also included "men at arms." These professional soldiers of Cartier’s "army" were blessed with Europe’s deadliest weapons. This is revealed in the "List of Men and Effects for Canada" (1538), which stated that munitions of war must be taken to be landed and installed in the Forts, including Artillery [cannons] and Arquebuses [muzzle-loaded firearms] …, Pikes [thrusting spears used by infantry], Halberds [long-handled axes topped with a spike], Lead, Cannon-balls, Shot & and other munitions.53 Reporting to the Spanish court, a spy estimated the quantities of weapons involved saying that Cartier was taking a great deal of good artillery, ... four hundred arquebuses, two hundred bucklers [shields], two hundred crossbows, and more than a thousand pikes and halberds.54 He also noted that "soldiers and mariners will carry ... bucklers, because the savages ... shoot with bows." If this wasn’t enough, more ammunition and weapons could be made because Cartier’s ships carried "fifty barrels full of iron and all the tools and instruments needed for ten ironworkers and smiths whom they are taking."55 Correcting Official Narratives One of the only Canadian government websites that mentions Cartier’s stockpile of weapons is the Canadian Military History Gateway. This project of the Directorate of History and Heritage at the Department of National Defence (DND) contains the online version of a three-volume set called Canadian Military Heritage. This colourful picture book is the official version of Canada’s military history. The author, Serge Bernier, began his history training with a BA from Canada’s Royal Military College and "ended his military career as a historian in uniform" at the DND Directorate of History in Ottawa. He then became DND’s Senior Historian and Director of History and Heritage.56 One section in this official history is called "Voyages of Discovery." In it Bernier quotes from 16th-century documents, but leaves out all references to Cartier as the military front man in the French king’s plans of conquest for "Canada." Instead, the DND’s fabrication uncritically describes Cartier’s so-called "discovery" of Canada by saying: [T]he land claims made by Cartier in the St. Lawrence Valley were recognized in Europe, where the territories that he discovered were identified on maps as New France.

It would have been unthinkable for these intrepid explorers to set out in search of unknown lands, inhabited possibly by natives of unknown disposition, but presumably hostile, without ensuring a minimum of security through effective weapons and men who knew how to handle and maintain them. Therefore, the sailors from all the European nations who signed on for these expeditions had to be able to become men-at-arms when danger threatened.57 (Emphasis added.) Excised from such simplistic government narratives of history is the fact that Europe’s warmongering royal patrons empowered Cabot and Cartier to use whatever violent means they needed to usurp the riches of the "New World." Canada’s official history also conveniently forgets that European conquerors were blessed with religious doctrines to justify the captivity, enslavement and murder of Indigenous peoples because they were considered not only culturally inferior, but also savage, animalistic and even demonic. Although Cabot and Cartier epitomise the religious brand of predatory imperialism that reigned in Britain and France, this stark reality has been largely whitewashed from official versions of Canada’s history. Thanks in no small part to government-issued fictions, many generations of Canadians never learned that, from its creation, the "Canada" project was driven by the European elite’s unquenchable quest for power, glory and wealth. Driven by raw greed, warmongering French and English monarchs facilitated the excursions of piratical "explorers" and tasked them to claim dominion over the lands, peoples and wealth of the "New World." For centuries, their crimes were cloaked in pious-sounding religious rationales that were overtly racist, xenophobic and culturally narcissistic. After 500 years, many Canadians are still so enamoured by the fiction that passes as official history that they are blind to this country’s deeply rooted criminal origins. The crimes of kidnapping, slavery and theft from Indigenous peoples are the most deeply rooted. Following in the centuries-old cultural tradition of treating Indians as outcastes and outlaws, Canadian "Correctional facilities" have always been disproportionately filled with Indigenous prisoners. (See "Indigenous Prisons and Slave Labour Today," p.43.) Many "corrections" are still needed to rid Canada of the structural violence and systemic racism that has evolved here over the past five centuries. One step in this process is to revise our understanding of history and to do away with national creation myths that portray Cartier and Cabot as heroic founders of Canada. We should instead acknowledge them as the official founding criminals of this fictive nation which has been built on a captivating web of myths that continue to deceive. References 1. Bruce Trigger, Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s ‘Heroic Age’ Reconsidered, 1985, p.5. http://books.google.ca/books?id=fchA2Ker1vQC 2. Alan Gordon, The Hero and the Historians: Historiography and the Uses of Jacques Cartier, 2010, pp.3, 72. http://books.google.ca/books?id=fYFSAAAAQBAJ 3. Ibid, p.156. 4. Trigger, op. cit, p.6. 5. Ibid. 6. Gordon, op. cit., pp.176, 187. 7. Marcel Trudel, "Jacques Cartier," The Canadian Encyclopedia, 1988. 8. Ramsay Cook, "Donnacona Discovers Europe: Rereading Jacques Cartier’s Voyages." In H.P.Biggar (trans. and ed.), The Voyages of Jacques Cartier, 1993. 9. John Pinkerton, A general collection of the best and most interesting voyages and travels in various parts of the World, Volume 2, 1819, pp.636-637. http://books.google.ca/books?id=-icZaHu5QAsC 10. Henry P.Biggar, op. cit., p.26. 11. Pinkerton, op. cit., p.638. 12. Ibid. 13. Henry H.Miles, The History of Canada Under French Régime, 1535-1763, 1872, p.6. 14. Biggar, op. cit., pp.43, 49. 15. Trudel, op. cit. 16. Donnacona, Canadian Encyclopedia 17. Lori Lee, "Enslavement of Native American Peoples," The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, 1997. Junius P. Rodriguez (editor) 18. Origin of the Name - Canada 19. Origin of the Name - Canada http://quebec400.gc.ca/pgm/ceem-cced/symbl/o5-eng.cfm 20. National Symbols http://canada150.gc.ca/eng/1344342322819 21. The St. Lawrence Iroquoians 22. Code of Ethics, Parks Canada Agency 23. Pinkerton, op. cit., p.661. 24. Biggar, op. cit., p.84. 25. Pinkerton, op. cit., p.662. 26. Biggar, op. cit., p.98. 27. HMCS Donnacona 28. Ibid. 29. Ibid. 30. Ibid. 31. Michaëlle Jean, Message on the occasion of the 475th anniversary of Jacques Cartier’s arrival in Gaspé, July 23, 2009. 32. Ibid. 33. Michaëlle Jean, Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michaëlle_Jean 34. "Grant of money to Cartier for his first voyage," March 18, 1533. Reprinted in Biggar, op. cit., p.117. 35. "Cartier’s Second Voyage," Reprinted in Biggar, ibid., p.82. 36. Letter from Lagarto to John the Third, King of Portugal, 22 January 1539. Proceedings of the Canadian Institute (1849-1914), 1935. p.8. 37. "Secret Report on Cartier’s Expedition: Report by a Spanish Spy on Jacques Cartier’s Preparations," April 1541. Reprinted in Biggar, ibid., p.152. 38. "Cartier’s Third Voyage." Reprinted in Biggar, ibid., p.97. 39. "Roberval’s commission," January 15, 1540. Reprinted in Biggar, ibid., p.147. 40. Robert la Roque de Roquebrune, "Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval," Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=396 41. "Letter from Lagarto ..." op. cit. 42. "Cartier’s First Voyage," Biggar, ibid., p.10. 43. Ibid., pp.37-38. 44. "Cartier’s Commission for his third voyage," 17 October 1540, and Roberval’s commission, January 15, 1540. In Biggar, ibid., p.135. 45. Christopher Columbus, Journal, October 11, 1492. 46. "Cartier’s Commission...," In Biggar, op. cit., p.135. 47. Ibid., p.126. 48. "List of Men & Effects for Canada," September 1538. In Biggar, ibid. 49. Biggar, ibid., p.37. 50. R.J.Knecht, Francis I, 1984. 51. "Cartier’s Commission...," and "Letters Patent from the Duke of Brittany empowering Cartier to take prisoners from the gaols," October 20, 1540. In Biggar, op. cit., p.139. 52. "Secret Report...," ibid., p.153. 53. "List of Men & Effects …," ibid., p.128 54. "Secret Report...," ibid., p.154. 55. Ibid., pp.152, 154. 56. Fonds 97/4 - Serge Bernier fonds www.archeion.ca/serge-bernier-fonds 57. "Voyages of Discovery," Chapter 2: Soldiers of the Sixteenth Century, Canadian Military History Gateway. |

|

The

above

article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017), magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT). The

above

article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017), magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this coupon, or use the paypal link on COAT's webpage. Subscription prices within Canada: three issues ($25), six issues ($45). If quoting this article, please cite the source and COAT's website. Thanks! |

|

You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion! You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion!

Captive Canada: This issue (#68) deals with (a) the WWI-era mass internment of Ukrainian Canadians (1914-1920), (b) this community's split between leftists and ultra right nationalists and (c) the mainstream racism and xenophobia of so-called progressive "Social Gospellers" (such as the CCF's Rev.J.S. Woodsworth) who were so captivated by their religious and political beliefs that they helped administer the genocidal Indian residential school program and turned a blind eye to government repression and internment during the mass psychosis of the 20th-century's "Red Scare." (Click here to read this issue online.) Read the introductory article here: "The Canada Syndrome, a Captivating Mass Psychosis" |

|

Not

surprisingly, various Government of Canada websites prefer the extraordinarily

deceitful rendition of history that expunges Cartier’s role in ushering in the

long Canadian tradition of holding Indigenous peoples captive. For instance, the

government’s Canadian Heritage website has a page called the "Origin of the Name

— Canada." It repeats the often-heard legend from Cartier’s second voyage:

Not

surprisingly, various Government of Canada websites prefer the extraordinarily

deceitful rendition of history that expunges Cartier’s role in ushering in the

long Canadian tradition of holding Indigenous peoples captive. For instance, the

government’s Canadian Heritage website has a page called the "Origin of the Name

— Canada." It repeats the often-heard legend from Cartier’s second voyage: Its

official symbol contains maple leaves arising from clasped red and white hands.

This cordial handshake, says DND, is used to "commemorate the meeting between

Chief Donnacona and Jacques Cartier at Stadacona." Meanwhile, the "maple leaves

are from the arms of Canada and indicate that the name ‘Canada’ came from the

Iroquoian word ‘Kenneta.’"29 So says the official government "Register of Arms,

Flags and Badges" of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. (See opposite page.)

Its

official symbol contains maple leaves arising from clasped red and white hands.

This cordial handshake, says DND, is used to "commemorate the meeting between

Chief Donnacona and Jacques Cartier at Stadacona." Meanwhile, the "maple leaves

are from the arms of Canada and indicate that the name ‘Canada’ came from the

Iroquoian word ‘Kenneta.’"29 So says the official government "Register of Arms,

Flags and Badges" of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. (See opposite page.)

Similarly,

Canada’s official history notes that after Cabot sighted land on June 24, 1497,

he "took possession of his discovery for England ...." The government’s childish

history then gives a defensive-sounding rationale for why great heroes like

Cabot and Cartier armed their crews with the deadliest of weapons available:

Similarly,

Canada’s official history notes that after Cabot sighted land on June 24, 1497,

he "took possession of his discovery for England ...." The government’s childish

history then gives a defensive-sounding rationale for why great heroes like

Cabot and Cartier armed their crews with the deadliest of weapons available: