Fictive Canada:

Issue #69,

Press for Conversion! (Fall 2017)

Click here

for info about symbolism of the front-cover collage |

|

|

Table of Contents 1-

True Crime Stories and

2-

John Cabot & Britain’s Fictitious Claim on

Canada: > Why “The Dominion of Canada”?

3-

Canada’s Extraordinary Redactions:

4-

Textbook Cases of

Canadian Racism:

5-

From Popes and Pirates to Politicians and

Pioneers: >

The Canadian Legal Fiction of

6-

Breaking the Bonds of Ignorance and Denial:

>

Oh say can you see? Blindsport

for Peaceable Racism

7-

Native

Captivity and Slave Labour 8-

Child Slavery in Canada’s

>

Jean L’Heureux:

|

Child Slavery in Canada’s

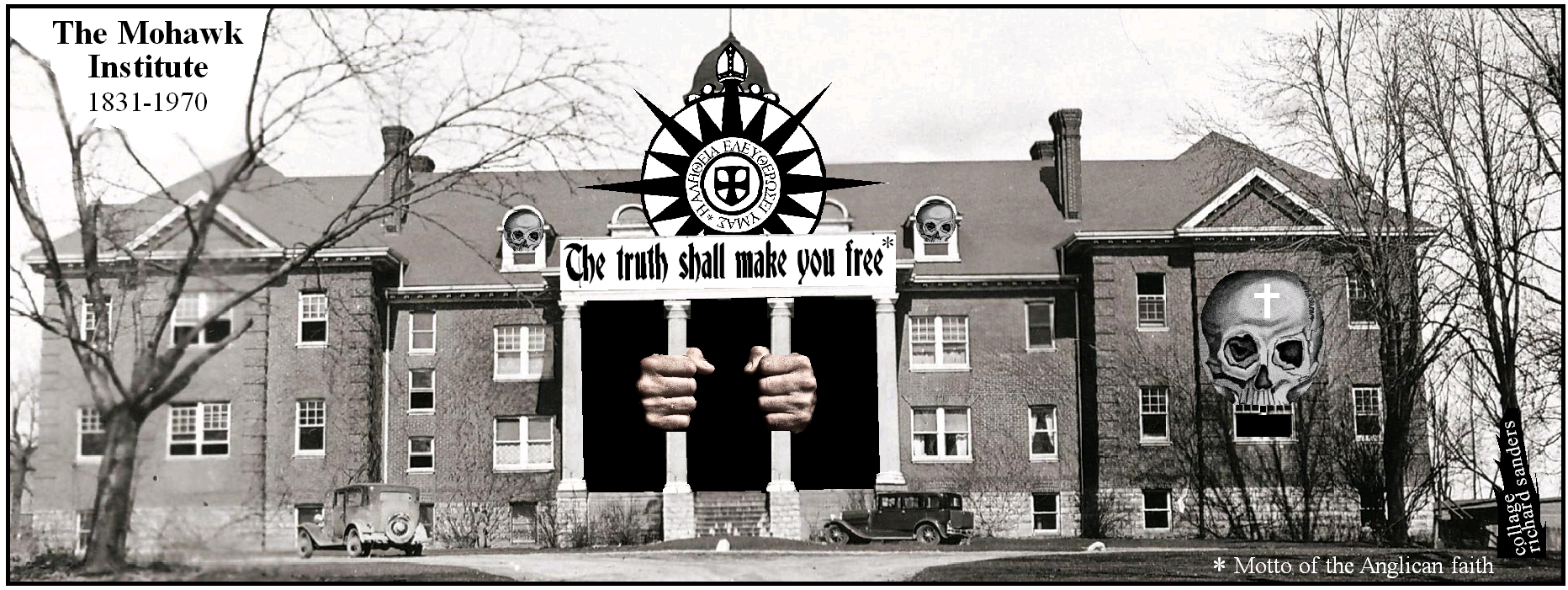

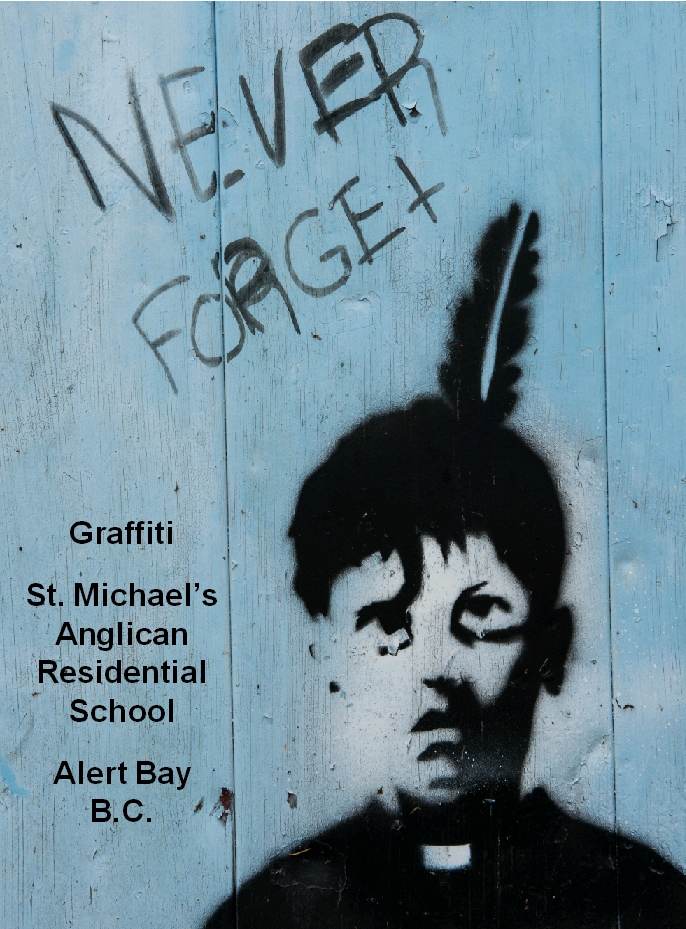

Officially, slavery in Canada was banned in the early 1830s. At the same time, the government and its allies in the churches were adopting so-called residential schools as the best way to finalise Canada’s genocidal assimilation of Indigenous people. In the process, a new form of child slavery took root in Canada. Slavery was banned throughout the British Empire when the Slavery Abolition Act came into force in 1834.1 That same year, the first dormitories were added to the Anglican Church’s Mohawk Institute in Brantford Ontario.2 This facility is often described as Canada’s first residential school. Not that the fall of slavery, or the rise of facilities to assimilate captive children, took place suddenly — history rarely turns on a dime. Slavery had begun to decline over the preceding decades in the northeastern American states. In Upper Canada, this slow process began in 1793 when Parliament banned the import of new slaves. Those already enslaved in the colony remained captive until their deaths, while the children of female slaves remained in bondage until age 25 and new contracts of indentured servants were not to be binding for more than nine years.3 Also in the late 1700s, well-meaning Christians in Canada were devising more effective ways to convert First Nations people. It was a time of experimentation, as churches created innovative new programs of genocide. One ingenious plan was to take children from their families and communities, and compel them into places of religious indoctrination and forced labour. These charitable programs were said to give uplifting education and job training for poor (allegedly stupid, lazy and uncivilised) children. They came to be called Indian residential schools. An early example of this racist segregation was begun by Anglicans near Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1787. By the 1790s, they had six "Indian colleges" boasting an inventive "apprenticing scheme." Historian James Miller explains that this effort to convert Catholic Indians, quickly

|

|

This Indian "college" scheme "became a system for funnelling philanthropic British pounds to colonial exploitation," said Miller, but ended in scandal as a "disastrous failure." An 1822 inquiry into the scam reported that while boys received little schooling, the girls received none at all. The "apprentices," it reported, were "treated as Menial Servants and compelled to do every kind of drudgery."5 Though publicly condemned for greed and sexual abuse, Anglican missionaries behind this pilot project were not prone to giving up. Their group, created by pilgrims in 1649 as the "Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England and the Parts Adjacent in America," was known as the New England Company. For over a century, this Anglican NGO and its agents had been dreaming up ways to put Indians to work. One such "scheme for turning Indians into a colonial workforce," said historian J.R. Jacob, emerged in 1662. Though never actualised, the plan was to use Indian labour to supply Britain’s imperial navy. This, they hoped, would aid the Reformation by arming the Protestant "crusade against the forces of Catholicism," while forcing "savages" to give up their "idle and lecherous habits."6 When their New Brunswick scheme ended in a shameful debacle, the Anglicans simply shifted operations to Upper Canada. Building on a Brantford day school begun in 1786, these missionaries opened a "manual labour school" in 1830. So began the Mohawk Institute. In its first decade, several girls left the facility to escape all the "menial labour they were required to do."7 Besides enduring religious brainwashing, the boys toiled at wagon-making, blacksmithing and carpentry, and the girls did weaving, sewing, spinning, knitting and general housekeeping.8

In 1841, Herman Merivale, an Oxford professor of political economy, published lectures on imperial strategies then used in British colonies to deal with "the Native question." These strategies, says University of Manitoba sociologist Russell Smandych, were: extermination (as was happening in Australia), slavery (as ... in Africa and elsewhere), insulation (or coercive segregation creating ‘Native reservations’); and amalgamation (or the rapid assimilation of Natives into white society).10 Merivale, who later became an Under-Secretary of State for British colonies in 1846, concluded his 1841 book by recommending that rapid assimilation was the most viable method. In 1842, the government created the Bagot Commission on Native Education. Its 1844 report called for a kinder, gentler means of genocide that was acceptable to the churches, locating farm-based, boarding schools far from the meddling interference of parents. This coincided with decisions by Anglican and Methodist Churchs that custodial facilities like the Brantford Institute were the best way to Christianise, civilise and Canadianise troublesome Indians. They were designed to exploit child labour to reduce costs.11 To implement its plan for "manual labour schools," Upper Canada’s government held a General Council of Indian Chiefs and Principal Men near Orillia in 1846. Capt. Thomas Anderson, the Visiting Superintendent of Indian Affairs, told the chiefs to "give up your hunting practices, and abandon your roving habits" because "you must cultivate the soil." With utter condescension he then told them that: your Missionaries have used their endeavours to divest you of Indian customs, and instruct you in the arts of civilized life, but it has not proved effectual .... because you do not feel, or know the value of education; you would not give up your idle roving habits, to enable your children to receive instruction. Therefore you remain poor, ignorant and miserable. It is found you cannot govern yourselves. And if left to ... your own judgement, you will never be better off ...; and your children will ever remain in ignorance. It has therefore been determined, that your children shall be sent to Schools, where they will forget their Indian habits and be instructed in all the necessary arts of civilized life, and become one with your white brethren.12 On top of these officially recorded insults, and the injustice of forcing children into "manual labour schools," Indians were told they had to pay 25% of their annuities for 20-25 years to pay the cost of this genocide.13 By the 1880s, Canada’s "mission schools" for Indians were using the "half-day system." Although children’s days were supposedly split between education and practical training, the system was "oriented towards extracting free labour, not imparting vocational training."14 While "education" largely meant religious indoctrination to convert children from their "heathen" ways, "vocational training" was a euphemism for what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) called "institutionalized child labour."14 Child labour was divided by gender. "All residential schools," said Miller, "tended to assign more institution-supporting toil to girls," such as cooking, cleaning and laundry. Boys did "most of the heavy outdoor labour"; they worked in barns and stables, constructed and maintained buildings and engaged in "strenuous activities such as cutting and hauling wood for the stoves and furnaces."15 The most "[p]ernicious forms of this involuntary servitude," Miller explained, were "apprenticeship programs and the ‘outing system’ that prevailed in many schools" from the 1880s until the 1950s. In summer, boys had "to work on farms owned by non-Natives," said Miller, and "were obviously a cheap source of labour at a time of peak demand." Others had to work in towns or cities. For example, boys from the Anglican Shingwauk Residential School left at 7 am to work for businesses in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, and did not return until 6 pm. Girls were used as domestic servants by rich families who wanted "maid[s], nannies, and general household assistants."16 The schools, said Miller, "resembled a method of furnishing cheap, semi-skilled labour to EuroCanadian homes more than it did a system of advanced training." The facilities, he concluded, had an "unhealthy emphasis on extracting labour" and "had little, if anything, to do with vocational and trades instruction."18 As sociologist Bernard Schissel of the University of Saskatchewan put it, residential schools were part of a "system of child and youth slavery under the guise of mandatory education." This "forced schooling," he said, "provided free child and youth labour for farms, industries, churches and households." The "expressed intent" of Canada’s mainstream churches was not to educate but to "destroy a culture and rebuild ‘Indian’ kids as active participants in the industrial economy."19 William Thomas, from Manitoba’s Peguis reserve, attended residential schools for 11 years. It took years, he said, to "mentally undo the devastation perpetrated therein by religious and other fanatics." One principal, he said, used to call us God’s children three times on Sundays at the three services and the rest of the week call us dirty little Indians.... We were mere numbers. Strapping, beatings, ... being tethered to the flag pole, half-day school with unqualified tutors, and slave labour the other half.20 The more parents learned about such conditions and how their children were forced to work, the more they objected. As the TRC stated, parents feared that their children were being prepared for a market economy in which human life was just another commodity and their children would be used as free labour .... The regimentation and discipline of the capitalist work world ... was far different from the highly autonomous world in which Aboriginal people had lived for thousands of years, so much so that it might well feel like a form of slavery.21 But it didn’t just "feel like a form of slavery," it was slavery. Forced labour permeated the system and outweighed any education offered at these custodial facilities. In 1896, the father of "pupil number 97" at the Anglican school in Battleford (now Saskatchewan) said that after five years, his son cannot read, speak or write English, nearly all his time having been devoted to herding and caring for cattle instead of learning a trade or being otherwise educated.22 Similarly, Walter McLaren, principal of the Presbyterian facility in Birtle Manitoba, wrote in 1912: "I know boys and girls who after ten years in our schools ... cannot read beyond the second reader, cannot write a decent letter."23 Describing the Catholic Grey Nuns school in Qu’Appelle Saskatchewan, in 1916, Indian Commissioner W.M. Graham said parents complained that children received "no education and that the sole aim" was "to get the children to school to make them work."24 The next year, deputy Indian Affairs minister Duncan C. Scott said getting children to attend was difficult because it "has been constantly represented" that they "are simply used as so much manual power to produce revenue." In 1922 he received complaints about an Anglican facility in Lytton B.C., where its principal, Rev. A. Lett said the children, "illfed and illclothed and turned out into the cold to work," were "unhappy with a feeling of slavery existing in their minds."25 In 1930, Graham reported that boys at Anglican and Catholic Indian boarding schools near Lethbridge, Alberta, were "working on the land from morning until night" and were "made slaves of, working too long hours."26 In a report on the difficulty of getting B.C. children to attend Edmonton’s Methodist residential school, an Indian agent noted that the chief complaint was that children were "continually working on the farm, thereby getting little or no education." Although they supposedly worked only half days, "[d]uring the harvest, older boys often spent the entire day on the farm." At that time, the school had 500 acres under cultivation, 15 horses, 59 cattle, 135 pigs, 50 chickens and 25 turkeys.27 The school’s principal, Joseph F. Woodsworth, "defended the intensive farm labour demanded of the students, arguing that ‘farm education’ was ‘the best kind of training.’" He blindly followed his church’s position that Aboriginal fishers, hunters, and trappers should transform into Christian farmers. He criticized parents who wanted their children ‘suddenly to become fine scholars...’ and praised the school’s regime for the ‘discipline and restraint’ it instilled in them.28 This principal who ran the school between 1919 and 1946, was the brother of Rev. James S. Woodsworth, a founder of the CCF and hero of many on the Canadian left. From 1885 to 1915, their father, James Woodsworth, was in charge of all Methodist missionary work in what became Canada’s four western provinces. (For details about the racist and xenophobic convictions of Rev. J.S. Woodsworth and numerous generations of his family, see Press for Conversion! issue #68.) Alvin Stonechild, who was born in 1934, attended the United Church’s Indian residential school in File Hills, Saskatchewan. "I had six years of work experience," he said. "We were driven like slaves. One could term this kind of work as child labour."29 In 1946, Campbell Papequash was forced to attend the Catholic residential school in Kamsack Saskatchewan. He bluntly described the work there saying: "there was a lot of slave labour." Isabelle Whitford, who entered the Birtle Manitoba residential school in 1948, said of this United Church facility: "We used to get on our hands and knees to wash the floors and wax them. We were like slaves."30 In 1951, Joe Kootney was one of the parents who complained about the overwork and harsh punishments of children at a United Church school in Morley Alberta. He summing it up by saying "the school is there for slavery now."31 And, as the Indian Association of Alberta told the Special Joint Committee on the Indian Act in 1946: "No white parents would tolerate for an instant such a form of education," which was "equivalent to child labour."32 The Mohawk Institute in Brantford Ontario also used Indian children as a slave labourers. Running from the 1830s until 1970, it was "the longest operating residential school for Aboriginal people in Canadian history."33 Though described as a "school" it was more a working farm than a place of education, where the children toiled in what can only be described as government-endorsed slavery, right down to stoking the 60-tonnes of coal that arrived each fall....34

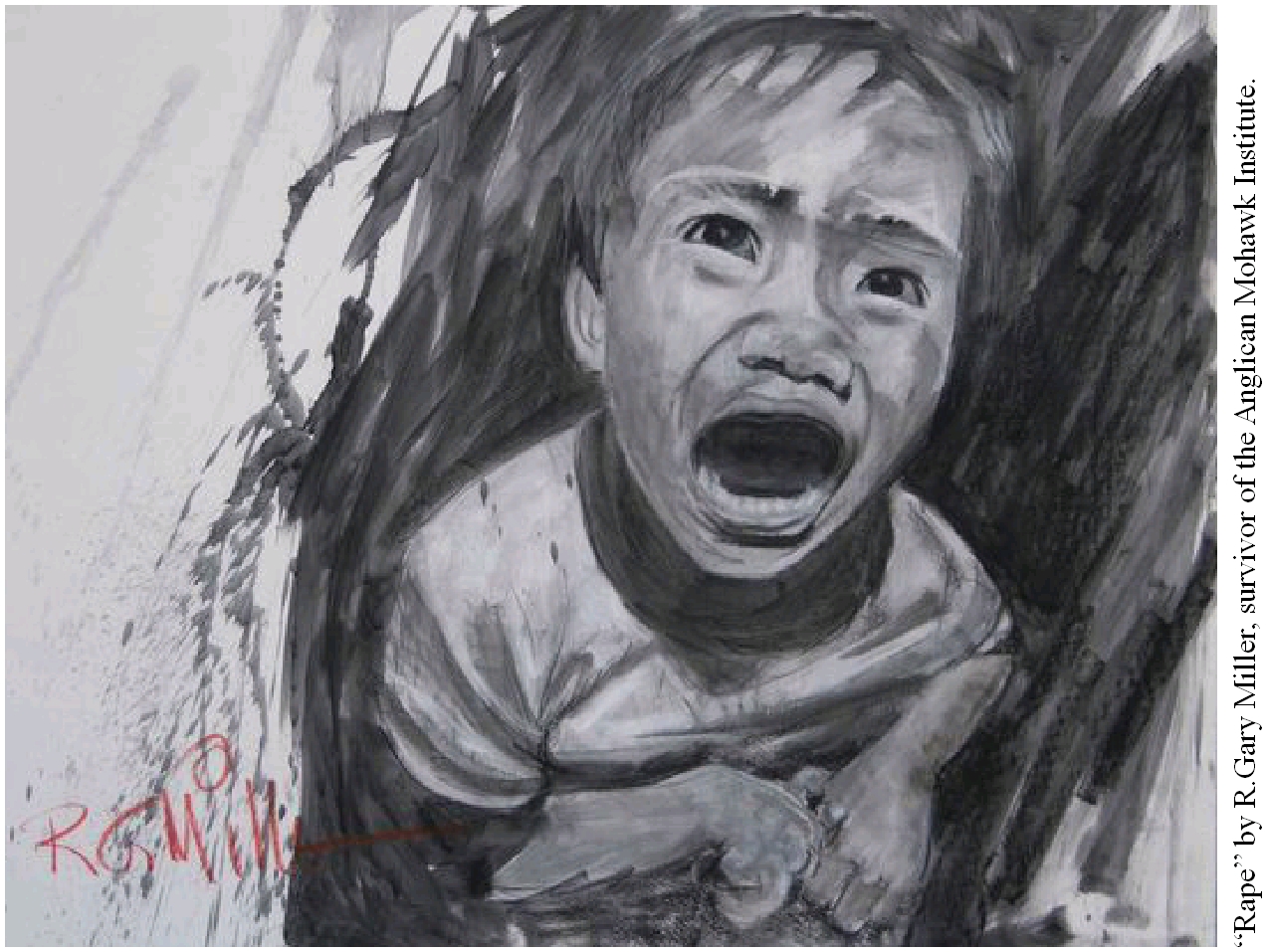

Besides being coerced into long hours of hard labour, many captives of Canada’s Indian residential schools also suffered years of sexual abuse. Though functioning as custodial facilities for genocidal assimilation into Canadian society, these institutions sometimes degenerated into places of sexual slavery. Paintings by R. Gary Miller reveal a glimpse into the hell of this experience. Born in 1950, Miller was an inmate of the Anglican Mohawk Institute from age three to fifteen. He was sexually assaulted by various authority figures in positions of trust, including staff, church members and a minister. College art teacher Steve Menhinick described Miller’s paintings as expressions of "extreme physical and sexual violence administered by the people of God." The "beatings, rapes and food deprivation" suffered by Miller "traumatized" him "to the point of suicidal depression throughout his life."35 The physical and sexual abuse of Indigenous children was endemic in Canada’s church-run residential schools. As the TRC reported, "[m]any students spoke of having been raped at school" and the "abuse of children was rampant."36 A First Nations Centre survey found that 70 percent of survivors reported physical assaults, and a third were sexually abused.37 Another study found that 80 percent of the system’s inmates reported abuse, and 48 percent suffered sexual abuse.38 This means that there are now between 26,400 and 40,000 Indigenous people who suffered sexual abuse in these "schools." Of the 80,000 living survivors of these institutions, about half filed injury claims for sexual and/or extreme physical abuse. By 2015, 85% of these claims were accepted and $2.81 billion was paid out in redress. An additional $1.62 billion in general compensation39 made it "the largest class action and settlement in Canadian history"40 and "the largest single recognition of criminal victimization in Canadian history."41 This huge case came too late for over 70,000 other residential school inmates who had died before 2005. For over a century, Indigenous voices were ignored by the powerful political, religious and legal authorities that were entrusted to oversee the genocide that passed as Indian education in Canada. Although 38,000 survivors reported sexual and/or extreme physical abuse, the TRC found fewer than 50 successful convictions of their abusers. When survivors "failed to find justice through police investigations and criminal prosecutions," they used civil courts. In the 1990s, survivors took legal actions against individual tormentors, and the church and state institutions that protected these criminals.42 Throughout their scandalous existence, complaints of sexual abuse haunted Canada’s shameful residential schools. Even the very first "Indian College" faced an inquiry in 1822 that "uncovered incidents of sexual exploitation of apprentices."43 In response, Anglican missionary perpetrators from the New England Company merely moved shop from New Brunswick to Upper Canada, where they opened the infamous Mohawk Institute. The last federally run residential school, which closed in 1996, was also Anglican. Beginning in 1874 near the Gordon Reserve in Punnichy, Saskatchewan, this was a place of systemic sexual abuse. William Starr, the residence director who was promoted to school administrator, was found guilty of sexually assaulting ten boys between 1968 and 1984.44 After Starr’s conviction, over 400 claims were filed against him by other survivors. By 1998, the Crown had settled about half of these out of court.45 Several survivors also reported abuse by other authorities in the facility, including Indigenous dorm supervisors and childcare workers, whom Starr reportedly "groomed to be sexual offenders."46 In 1993, Starr was sentenced to 4½ years in jail for 16 years of sexually abusing children imprisoned by this Anglican facility. Another key case in the mid-1990s convicted Arthur Plint, a pedophile at the Alberni Indian Residential School on Vancouver Island. Plint, its dormitory supervisor from 1947 to 1968, was sentenced to 11 years in prison. This United Church facility held Indian children captive from its Presbyterian beginnings in 1891 until it closed in 1973. B.C. Supreme Court Justice Douglas Hogarth called it the worst sexual abuse case he had seen in 45 years. Children "were prisoners in the residential school," said Hogarth, "and [Plint] knew it." Calling Plint a "sexual terrorist," Hogarth denounced the entire "Indian residential school system," as "nothing more than institutionalized pedophilia."47 Most of the 27 survivors who started the suit in 1996 settled out of court. Only one remained in 2005 when the Supreme Court forced the payment of $200,000 by the government (75%) and the United Church (25%). Legal proceedings revictimised survivors of sex abuse who faced harsh cross-examination by government and church lawyers.48 Chief Robert Joseph of the Gwawaenuk First Nation was appalled that both church and state used defence strategies "to minimize their financial liability." Calling it "depraved and morally indefensible," Joseph said court acceptance of these strategies showed "Canadian society at the highest levels has not abandoned its abusive ways."49 The Plint case forced the RCMP to investigate complaints of endemic sex abuse in the dozen other B.C. "residential schools." In 2015, the TRC described the federal government’s interference in this police investigation, saying various injustices hampered the legal system’s ability to prosecute sex offenders who had operated with impunity in residential schools.50 In 1997, a year after the last Indian residential school finally closed, and amidst a growing number of embarrassing public cases, the federal justice minister asked the Law Commission of Canada to "assess processes for redressing the harm of physical and sexual abuse inflicted on children who lived in institutions ... run or funded by government."51 Besides Indian residential institutions, this included numerous other church-run facilities that victimised children with "developmental and physical disabilities, ... mental disorders, orphans, and even those ... simply born outside marriage."52

The Law Commission’s 2000 report gave key lessons about how child abuse in so many Christian institutions had degenerated into forms of sexual abuse. One recurring factor was the "enormous power imbalance" between children from poor, marginalised and powerless social groups (largely racial and ethnic minorities), and the huge state and religious institutions with "significant social power" that are "potent symbols of authority."53 Chief among these are Canada’s largest churches and their government benefactors. Another key lesson of the report had to do with the trust, faith and deference that was blindly bestowed upon Canada’s most powerful religious institutions. Once forced into residential schools, inmates were socially invisible, banished to what the Commission called "a different world" where they were "out of sight" and "out of mind." Canadians had such overwhelming fealty and loyalty to the churches that they did not dare imagine what could go wrong. As the report stated: For many communities, the idea that ministers, deacons, priests, nuns, or members of lay orders could commit acts of physical and sexual child abuse was unthinkable. Even today, to accept the extent of the abuse that was committed, and the failure of those in charge to prevent or stop it, is to have one’s faith in governments and churches seriously undermined. Many would rather believe that the abuse did not occur, or that the reports have been wildly exaggerated.54 So great was the confidence given these Christian education schemes, that even some Indian parents — particularly Christian converts — turned a blind eye to the horrors faced by their own children. As the TRC said regarding sexual assaults. Family members often refused to believe their children’s reports of abuse.... This was especially so within families that had adopted Christianity, and could not believe that the people of God looking after their children would ever do such things.55 (Emphasis added.) For example, when Dorothy Beaulieu revealed she was being sexually abused by a Catholic priest at the Fort Resolution Residential School, she was accused of lying. "Don’t make up stories," said her aunt. "They work for God, and they can’t do things like that."56 Christianised children were led to believe the fiction that they were safe in the embrace of church authorities. This was noted by the judge in the 1998 case against Derek Clarke, a dorm supervisor with no training in child care at St. Georges Residential School near Lytton, B.C. As Judge Janice Dillon stated in her decision The Anglican Church through the principal of the residence ... exercise[d] power over the plaintiff as it pertained to his moral and emotional well-being and dignity. It did so daily by imposing religious practices and influence which involved an interaction that created trust and reliance. The plaintiff absolutely trusted that he would be properly cared for, especially because this was an Anglican institution. The fact of Anglicanism lent a superior moral tone to the residence that created an additional level of assurance.57 In this landmark case, Judge Dillon found that despite complaints of sexual abuse, the Anglican Church took no action. For eight years, Clarke sexually abused at least seven children. Saying the principal, Rev. Anthony Harding, "ought to have known or ... was wilfully blind," the judge concluded that Clarke’s crimes were covered up by the principal, who "also sexually assaulted male students."58 Dillon assigned 40 percent of the liability to the federal government, and 60 percent to the church. The school, said Dillon, was "a pervasive, purposeful Anglican environment ... run with military precision" that included "indoctrination into a routine of daily prayer, military style housekeeping, and regimented activity."59 Like the Mohawk Institute, it too was founded by the New England Company. Those assimilated into Christianity were more prone to have confidence that church officials would protect children’s safety. Many were captivated by the belief that God was looking over the institutions through his earthly representatives, namely, the facilities’ pious staff. In truth, oversight was virtually nonexistent. "Too often," said the Law Commission, "there was little oversight of any kind ... on the daily activities, the level of discipline and the quality of care that children received." This blind faith exposed thousands of children to years of repeated sexual abuse by their religious captors. The sexual abuse that pervaded Canada’s mission schools, has disturbing parallels with confidence schemes. Like all con artists, the pedophiles operating within these faith-based institutions gained the confidence of their victims. That trust was the prime advantage they wielded over their victims. The Law Commission report described how those in positions of religious authority used their powerful advantage to sexually abuse children: Some experienced the perversion of what begins as an affectionate and trusting relationship with a person in authority, to one where sex is eventually introduced and demanded.60 By operating under a religious cover to carry out Canada’s genocidal plan of assimilation, abusers enjoyed a tremendous advantage over their victims. It also cloaked them from outside scrutiny. Christianity commands such an aura of respect, decency and honesty in Canada’s domineering Eurocentric society, that church figures acted with impunity. And, after centuries of proselytisation, churches also commanded the faith of many Indigenous children, parents and communities. The greater one’s loyalty to Canada’s political, legal and religious institutions, the harder it is to believe that — for more than a century — residential school authorities perpetuated and covered up forced labour and child abuse that amounted to sexual slavery. To overcome some of the obstacles that prevent reconciliation with the truth, it is useful to expose the fiction that residential schools were educational facilities. In reality, though disguised as schools, these institutions of genocide were actually more like forced-labour reformatories, correctional centres or prisons for children.

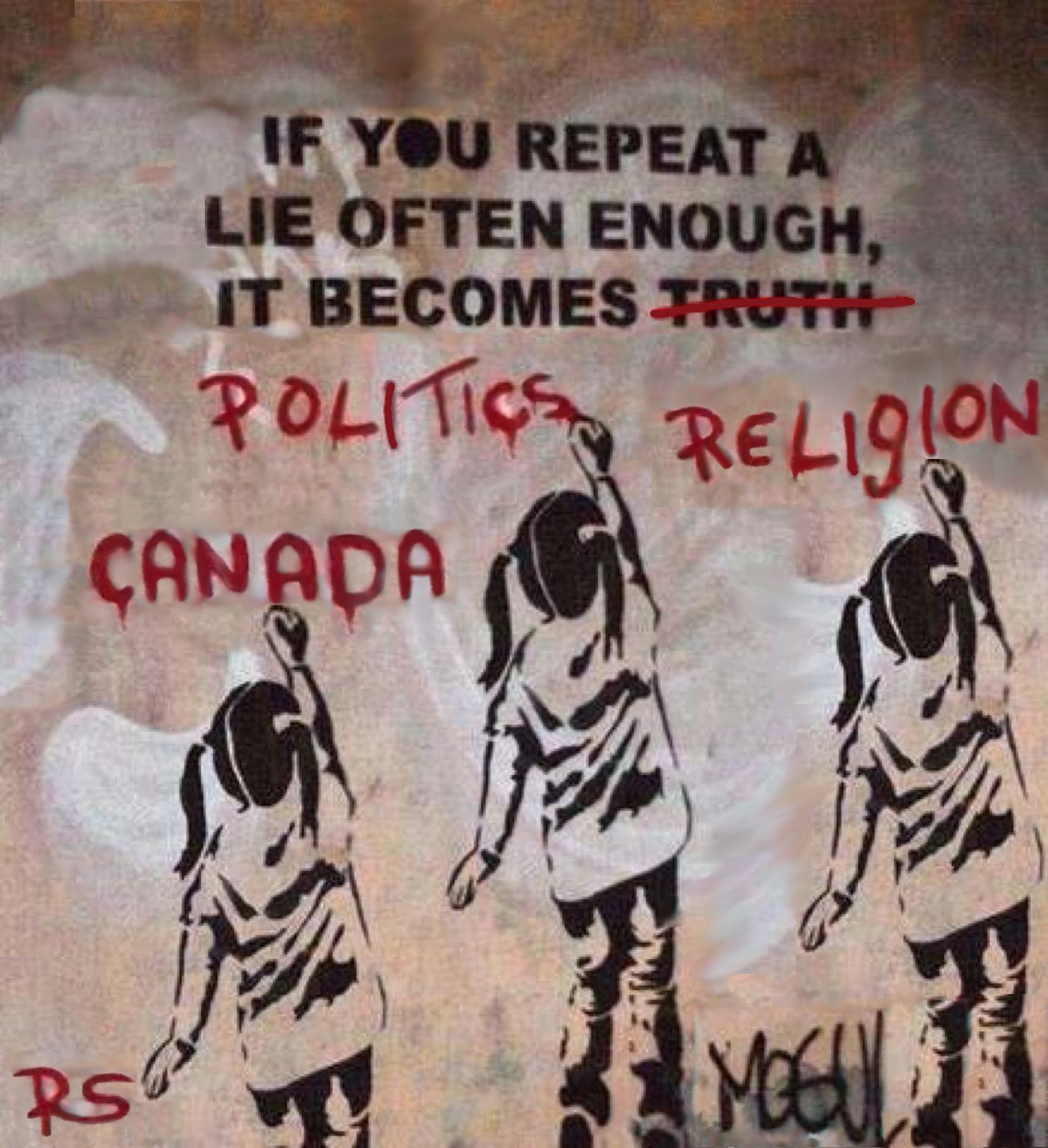

The term "residential school" is a fictive use of words that is, at best, euphemistic. Stretching the truth beyond credulity, it hides the real function of these cultural reformatories. Referring to these religious detention centres as "schools" furthers the pretence that they provided meaningful learning environments. This deception is part of an officially promoted confidence scheme disguising the truth that these fake schools were central to Canada’s strategy of genocide. Not only did they impose the cultural captivity of foreign religious beliefs, they held children physically captive and exploited them as slave labour. To grasp just how ludicrous it is to see these custodial facilities as "schools," it is worth looking at etymology. In Latin, schola meant "leisure" or an "intermission of work." An even older Greek word, skhole, meant "free time, leisure, rest, ease or idleness."61 It is, then, difficult to speak of Indian "residential schools" without facing some absurdly duplicitous contradictions. What form of leisure, rest or freedom from work do inmates receive when held against their will in "schools" that compel them to labour as slaves? Canadian officials sometimes showed a glimmer of understanding that at least some of these facilities were not actually schools. In 1949, the superintendent of Indian Affairs in Edmonton, H.N. Woodsworth, reported that: "As there are no qualified teachers employed at the Ermineskin Indian Residential School, this institution cannot truly be called a school." The principal of this Catholic facility had recently told Woodsworth that, due to financial problems, "no qualified teacher can be employed in the immediate future."62 This lack of real teachers was not new. During most of its 150-year history, Canada’s residential schools did not rely on certified teachers. This seems to have been especially true of Catholic facilities. As the TRC noted most of the teachers in the Roman Catholic schools — and these constituted the majority of the schools — were members of female religious orders .... Many of the women teaching in these schools did not have formal training as teachers.63 Despite some efforts to hire real teachers, by 1953, 79 of the 198 instructors (40 percent) at Catholic "residential schools" had no teaching credentials. In fact, only 27 percent of the unqualified "teachers" had finished high school. And, a shocking 13 percent had never even started high school.64 Even by 1960, said the TRC, only a "few of the teachers at the Roman Catholic residential schools in northern Alberta had the appropriate qualifications."65 The Catholic Church was not alone in hiring fake teachers. In a review of all residential schools, R.F. Davey, the chief of education for Indian Affairs, reported that in 1950 "over 40 per cent of the teaching staff had no professional training."66 Within four years, 23 percent still had no credentials, and by 1959, this was down to 13 percent. But in 1969, the government reported that Indian schools still had "the same number of unqualified teachers" as they had a decade earlier.67 Even if all these teachers had proper qualifications, this would not have remedied these fake schools. The whole genocidal program needed replacement. No amount of tinkering reforms with teacher training could fix Canada’s apartheid school system. Because their objective was not education but religious conversion, cultural assimilation and forced labour, it did not matter whether "teachers" had the proper credentials. As English satirist Stephen Gosson said in 1579, you can’t "make a silk purse of a sowes ear."68 By the late 1940s, even the government was saying that its residential school program had to end. At hearings of the joint parliamentary committee on Indian Affairs (1946-1948), Indigenous organisations demanded "an end to the policy and practice of segregated education." The TRC notes that state officials soon "determined that the system should be shut down completely as soon as possible."69 Despite this, the abysmal system was kept in place for another half century. Instead of ending the apartheid system it had supposedly decided to abolish, the government toyed with various meaningless reforms. While they increased the number of qualified teachers, government efforts were overshadowed by ... a most fundamental impediment. Both the curriculum and the pedagogy, which were not in any way appropriate to the culture of the students, made it difficult for the children to learn.70 Another factor is that few of the schools’ principals had teacher training. Almost all of them were members of the clergy .... To the churches and the government, their skills as farmers and managers were as important as their knowledge of education.71 Some government employees reported that churches put too much "weight on the schools as missionary endeavours [rather] than as educational institutions."72 In 1946, school superintendents in Alberta reported that so-called "mission schools" did "not begin to approach the standards that we set for our public schools." This, they said, was because "qualified teachers are seldom employed," they often ignored provincial curriculum and, their libraries were "inadequate in practically every case. Most of the literature supplied is religious in nature."73 The goal of these "schools" was not to educate, but to instil religious beliefs to capture children’s hearts and minds. Indianness was to be wiped out and replaced with the advanced culture of Christian values. In the name of god, progress and civilisation, the often well-meaning purveyors of this religious process inflicted generations of genocide and slavery. Enslaved by Canadian Hubris Enslaved by the arrogant self-confidence of cultural narcissism, Canada’s political, religious and economic elites justified this country’s apartheid system with narratives of pious superiority. With wilful blindness, the obvious harm that Canada inflicted on Indigenous peoples was diligently ignored. Only by looking away from these arrogant crimes, could Canadians continue to invest their trust in church-run assimilation programs that promised a final solution to their "Indian problem." The missionary focus on converting "savage heathens," and the political dream of seizing their land, came together in the imperial project called Canada. As the country’s genocidal residential schools quickly degenerated into systemic physical and sexual abuse and outright slavery, Canada’s nation-building reverie increased the nightmare faced by First Nations. While officials of church and state averted their gaze from the genocide for as long as possible, the public also cultivated a contrived, blissful ignorance. This learned ability to ignore such abhorrent crimes as the slavery imposed on "residential school" inmates, relies on an overconfidence in Christianity and a smug faith in political myths that Canada is a caring nation built on glorious moral values. Although Canada’s "residential school" program resuscitated the banned institution of slavery, it was portrayed as a benevolent gift to assist poor, uncivilised Indigenous children. In reality, this "gift" of a good Christian education was a part of a criminal enterprise to deprive Indigenous peoples of their culture, destroy their families, communities and economies, plunder their land base, kidnap their children, and forced them into slavery. This massive theft of culture, land and labour, disguised as religious philanthropy, was part of the full-spectrum war waged by Europeans against First Nations. Such genocidal schemes require mass consent and the participation of large social institutions. The whole racist plan was made palatable to the public, by camouflaging it behind grand myths extolling the supposed superiority of Canada’s Christian civilisation. National narratives of Canadian exceptionalism still permeate mainstream culture and even persist in progressive movements that affirm the official folklore of our beloved "Canadian values." As long as popular culture remains enslaved by captivating social delusions such as those applauding Canada as a "Peaceable Kingdom," we will not be able to face the bitter truths about our ongoing colonialism. Neither can we expect resistance to the injustices and warmongering practices that this country continues to profit from, as long as mainstream Canada remains unschooled in the reality of this country’s genocide of Indigenous peoples. References 1. Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 13, 1835. 2. The Mohawk Institute–Brantford, ON 3. An Act to Prevent the Further Introduction of Slaves..., 1793. 4. James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools, 1996, p.65. 5. Canada’s Residential Schools (CRS): The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939, Vol.1, 2015, p.69. 6. J.R. Jacob, "The New England Company, the Royal Society and the Indians," Social Studies of Science, 5, 1975, pp.451-453 http://www.jstor.org/stable/284808 7. CRS, The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.70. 8. Miller, op. cit., p.73. 9. Ibid., p.75. 10. Russell Smandych, "The Exclusionary Effect of Colonial Law: Indigenous Peoples & English Law in Western Canada, 1670-1870," Laws & Societies in the Canadian Prairie West, 1670-1940, 2005, p.140. 11. Miller, op. cit., pp.76-84. 12. Minutes, General Council of Indian Chiefs and Principal Men [on] ... the Establishment of Manual Labour Schools, Orillia, July 30-31, 1846, pp.6-7. 13. Ibid., p.6. 14. Miller, op. cit., p.157. 15. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Final Report, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), pp.77-78. 16. Miller, op. cit., p.224. 17. Ibid., p.253, 256 18. Ibid., p.253. 19. Bernard Schissel, "Justice Undone: Public Panic and the Condemnation of Children and Youth," Moral Panics Over Contemporary Children and Youth, Charles Krinsky (ed.) 2008, p.25. 20. Pauline Comeau and Aldo Santin, The First Canadians: A Profile of Canada’s Native People Today, 1995, p.128. Anne McGillivray, "Therapies of Freedom: Colonization of Aboriginal Childhood," UBC Legal History Papers, 1995. 21. CRS, The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.248. 22. Miller, op. cit., p.166. 23. CRS, The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.341. 24. Ibid., p.343. 25. Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Looking Forward, Looking Back, Final Report, Vol.1, 1996, p.290. http://qspace.library.queensu.ca/handle/1974/6874 26. CRS, The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.341. 27. Edmonton Indian Residential School 28. Ibid. 29. CRS, The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.343. 30. The Survivors Speak: A Report of the TRC of Canada, 2015, pp.79-80. 31. CRS: The History, Part 2, 1939 to 2000, Vol.1, p.385. 32. CRS: The History, Part 2, op. cit., p.26. 33. CRS, The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.66. 34. Mark Bonokoski, "The elder & the Native artist," Toronto Sun, Dec.13, 2008. 35. Ibid. 36. Phil Fontaine, A.Craft, TRC, A Knock on the Door: The Essential History of Residential Schools, 2016, pp.93-94. 37. CRS: The Legacy: The Final Report of the TRC of Canada, Vol.5, 2015, p.145. 38. Roland Chrisjohn, Sherri Young, Michael Maraun, The Circle Game: Shadows and Substance in the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada, 1997, cited by First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey, 2002/2003. 39. Bill Dunphy, "Brantford school a key tool in 150-year effort to assimilate First Nations children," Hamilton Spectator, August 29, 2015. 40. CRS: The Legacy... op. cit., p.200. 41. CRS: Final Report of the TRC, Vol.1, Summary, pp.178-179. 42. Ibid., p.166. 43. CRS: The History, Part 1, op. cit., p.69. 44. David, Napier, "Sins of the Fathers," Anglican Journal, May 2, 2000. 45. Bruce Feldthusen, "Civil Liability for Sexual Assault in Aboriginal Residential Schools," Canadian Journal of Law and Society, April 2007. 46. "Residential Church School Scandal," Maclean’s, June 26, 2000. 47. Susan Lazaruk, "77-year old pedophile sentenced to 11 years," Windspeaker, Vol.13, Issue 2, 1995. http://www.ammsa.com/node/20552 48. Peter O’Neil, "BC residents remember how the fight began," Vancouver Sun, June 3, 2015. 49. Paul Barnsley, "Alberni Indian Residential School trial Decision ‘shocks,’" Wind-speaker, Vol.19, No.4, 2001. 50. Final Report TRC, op. cit., pp.165-168. 51. Law Commission of Canada, Restoring Dignity: Responding to Child Abuse in Canadian Institutions, 2000, op. cit., p.4. 52. Ibid., p.5. 53. Ibid., pp.4-5. 54. Ibid., p.5. 55. Fontaine, et al, op. cit., p.95. 56. The Survivors Speak..., op. cit., p.161. 57. FSM vs. Clarke, August 30, 1999. 58. Ibid. 59. Ibid. 60. Law Commission ..., op. cit, p39. 61. "School," Etymological Dictionary http://www.etymonline.com/index.php 62. CRS: The History, Part 2, op. cit., p.117. 63. Ibid., p.116. 64. Ibid. 65. Ibid., p.117. 66. Royal Commission ..., op. cit., p.276. 67. CRS: The History, Pt. 2, op. cit., p.115. 68. Stephen Gosson, The Ephemerides of Phialo," 1579, p.62v 69. Royal Commission ..., op. cit., p.278. 70. Ibid., p.277. 71. Ibid., p.115. 72. Ibid. 73. Ibid., p.119. |

|

The

above article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017),

magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT). The

above article was written for and first published in Issue #69 of

Press for Conversion (Fall 2017),

magazine of the

Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade

(COAT).Please subscribe, order a copy &/or donate with this coupon, or use the paypal link on COAT's webpage. Subscription prices within Canada: three issues ($25), six issues ($45). If quoting this article, please cite the source and COAT's website. Thanks! |

|

You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion! You

may also be interested in this back Issue of Press for Conversion!

Captive Canada: This issue (#68) deals with (a) the WWI-era mass internment of Ukrainian Canadians (1914-1920), (b) this community's split between leftists and ultra right nationalists and (c) the mainstream racism and xenophobia of so-called progressive "Social Gospellers" (such as the CCF's Rev.J.S. Woodsworth) who were so captivated by their religious and political beliefs that they helped administer the genocidal Indian residential school program and turned a blind eye to government repression and internment during the mass psychosis of the 20th-century's "Red Scare." (Click here to read this issue online.) Read the introductory article here: |

|

Sexual

Slavery, Con Artists

Sexual

Slavery, Con Artists  Religious

Lessons Learned

Religious

Lessons Learned Fake

Schools,

Fake

Schools,