|

|

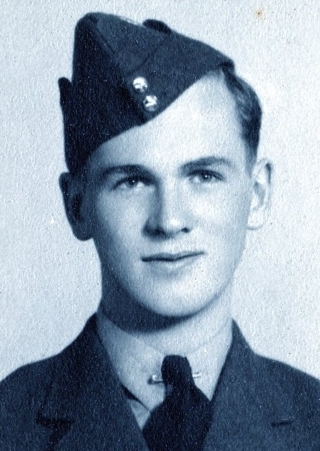

L.A.C. |

|

This journey opened doors for him in many ways. The war forced him off the farm and into a wider world which he would continue to explore throughout his life. (Learn more about dozens of foreign travels which Roy did for business and pleasure.) The war also introduced him to Sylvia Whittlesey, his "warbride" from England who he met on the way home from India. (See the map of India which she sewed for him noting all of the places he had visited there.) By

early 1943, Roy was living in far-away India where he spent two years

serving Britain's Royal Air Force (RAF) with Squadron 354.

This squadron, part of the RAF's South East

Asia Command, used Liberator bombers to do maritime

reconnaissance patrols over the Bay of Bengal and along the Arakan coast

of Burma, just west of British-occupied India. Liberators were also

used to bomb Japanese submarines, supply ships and onshore military

targets. Imperial Japan had invaded the

British colony of Burma in 1942 and occupied

it with military forces until 1945. RAF Liberators were

equipped with RADAR ("RAdio Detection And

Ranging") primarily so that they could track

enemy

ships and submarines. RADAR altimeters were

used to keep the planes at low altitutes so they could look for subs.

They were also

useful

in guiding them back to air bases after the

completion of long missions. Some flights ventured thousands of

kilometres out into the Indian Ocean. The above

photo of a Liberator

bomber was taken in 1945 at Cuttack India where Roy was deployed with

the 354th for most of the war. Roy and others were sent to the

US Technical Training Center in Corpus Christi, Texas. There they had

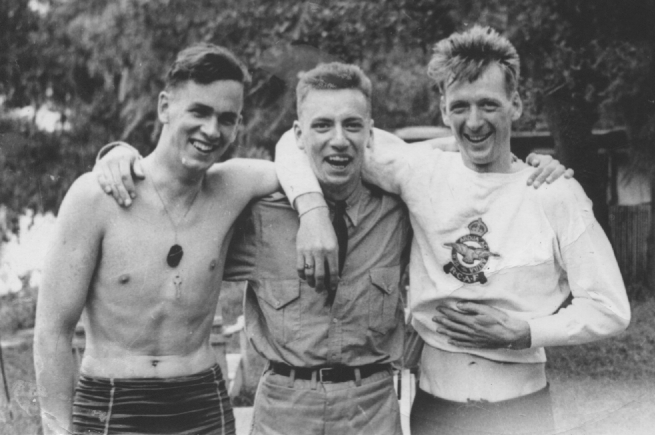

RADAR training and acclimatization for the hot coastal weat While in Texas, Roy and the boys apparently had a bit of time off, a free weekend perhaps? It seems doubtful that they were supposed to venture far from the base but he and a couple of others decided to take off to Florida for some R&R. Some mishaps occurred along the way and they were concerned about making it back to the base on time. While hitchhiking, a convertible stopped to pick them up. Imagine their surprise when the car contained two young women! Military life was certainly a far cry from his extremely shelted upbringing in a strict religious home by a single mother from good Quaker stock. (Photo at left is Roy with fellow RADAR trainees Bill Wright and Joe Ward in Houston 1943.) Roy and the other

Canadian RADAR techicians were then sent to Britain. From there they

headed to India via Egypt.

During their stopover in Cairo, Roy had the chance to see some other

sights that he could only have imagined in The County, namely, the pyramids of Giza.

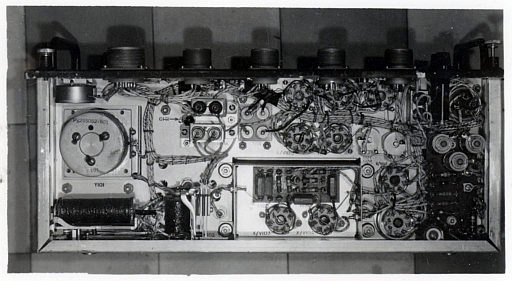

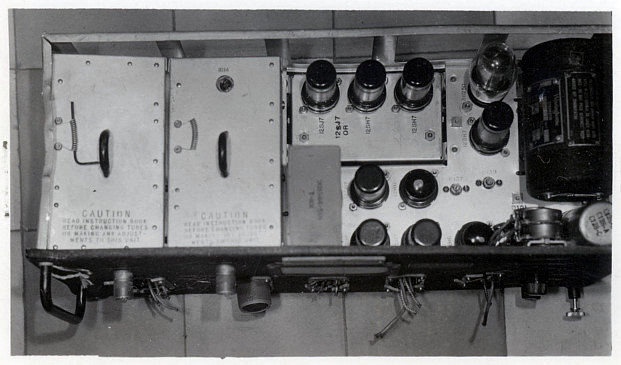

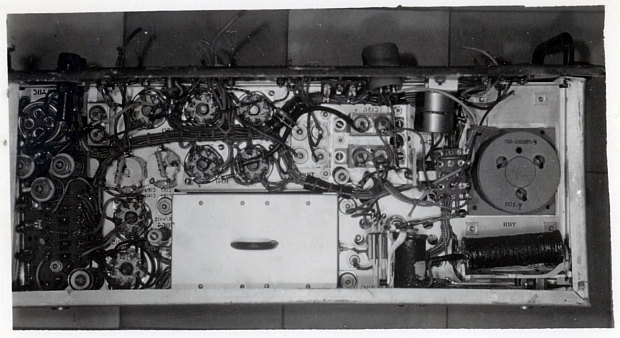

At that time, RADAR was such a new and extremely top-secret technology that Roy and the others were not even allowed to say the word RADAR, let alone reveal anything about it to anyone, including even their military superiors! This led to some problems on the next leg of their journey. (These four photos of top-secret RADAR equipment were taken by Nazi forces when they shot down a Liberator bomber in Europe.)

In India, Roy was known to the other crew members as "Sandy." Officially though, on the books, he was referred to as LAC C.L. Sanders. (Note: LAC which stands for Leading Aircraftman was the highest of three ranks for aircraft crew. However, it must also be noted that all Aircraftmen, Leading or not, were well down from the pilots and other officers.) The photo below is from p. 68 of an online photo album called "354 Squadron RAF Photos via J. Badgley." Another photo in that album, on p.72, shows many of the same aircrew members.

There's even a little documentary about the Canadians of the 354th. It's called "Quiet Heroes: Story of a Forgotten Squadron." But not all data from the 354th has gone AWOL. There's at least one military document that I found which lists Roy and several other Airmen from the photo above. In some data from a "Form 540" dated June 1944 which makes reference to "officers, SNCOs and Airmen" who were "authorized to wear the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal Ribbon and the Maple Leaf Emblem." The list of names includes the following: LAC Cardinall, LAC Jameson, LAC Ward, LAC Whyte, LAC Hughes, LAC Rasmusson, LAC Wickware, LAC Stringer, LAC Sanders." (354 Squadron RAF 1943 to 1945: A Record of their Operations, pp.125-126). (In the artificially-coloured photo of "Sandy" above, you can see the single propeller badge signifying his rank as Leading Aircraftman. Above that, on his right arm is a badge showing five lightning bolts coming down. It is likely related to his RADAR work.)

Tasked to fix and maintain RADAR equipment that was used aboard Liberator bombers, Roy and other members of 354 Squadron's ground crew did not take have to fly aboard the Liberators. However, he did speak of at least one occasion when he did take part in a Liberator mission out over the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean. Although it's not clear why he was needed onboard during that mission, the memory I have is that he did not enjoy the very long flight and he was quite glad to be back on the ground when it was over. During the RAF's Burma campaign, Liberator bombers flew missions that were as long as eighteen hours and covered round-trip distances of up to 3,000 miles (i.e., 4,800 kms).

This same book describes the 354th's return to Cuttack in early 1945 and the missions there:

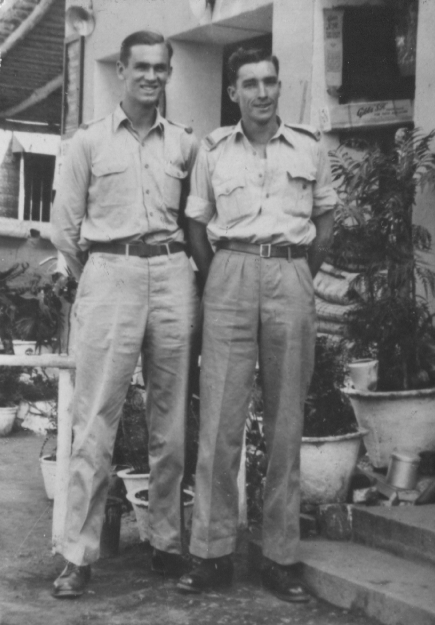

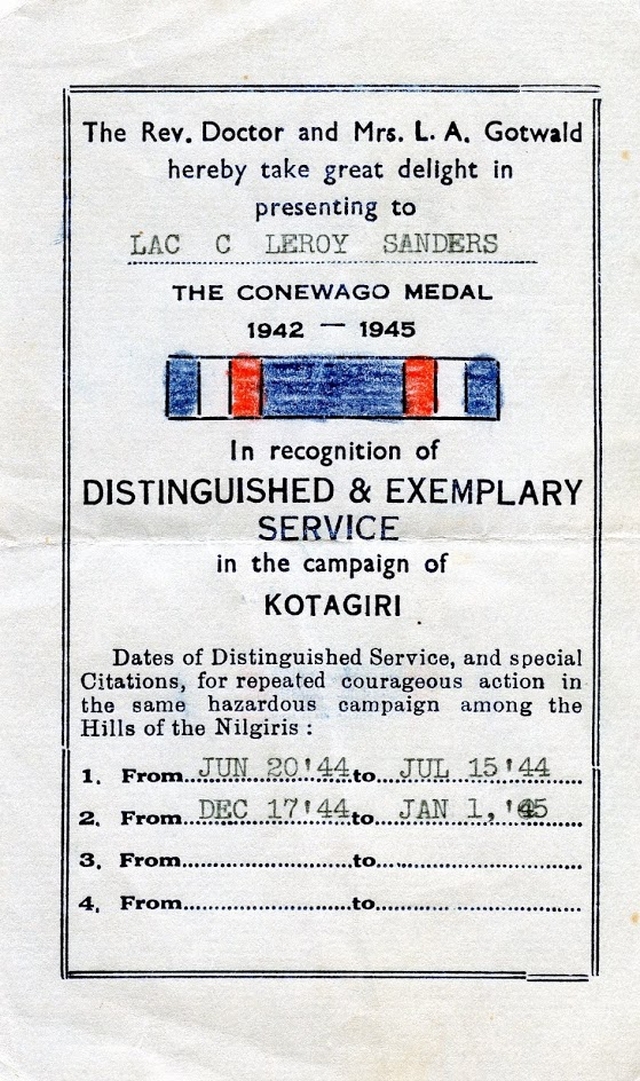

What this book does not mention is that in mid- December 1944, before returning to Cuttack some RAF crew were deployed to south India. The picture, at right, shows Roy with an unknown colleague in Bangalore, where there was a major RAF air station. Besides noting this location, Roy wrote on the date on the back of the photo, "Feb 1945." Roy is known to have participated in the Kotagiri military campaign in the Nilgiri mountains south of Bangalore. He received the Conewago Medal "in recognition of distinguished and exemplary service in the campaign of Kotagiri"...."for repeated courageous action" in the "hazardous campaign among the Hills of the Nilgiris." (See image at below.) Since that campaign ended on January 1, 1945, what was Roy still doing in the region in February? The answer to this may be related to another hazard that they faced in India.

Roy also shared memories of other threatening Indian wildlife that came

from the air. These were the vultures

that soared above the airbase in Cuttack but would suddenly swoop down to grab the food

from their hands!

This happened so often that aircrew learned to always cover their food with

another plate when carrying it around outdoors.

Roy would sometimes contrast his accounts of bad military food, with tales about the fine cuisine enjoyed by officers. These higher ranks even also said to have been served port and sherry with their delicious weevil-free meals. The only way it seemed that Roy and the other lowly-RADAR technicians could enjoy good, home-cooked, weevil-free food was to do it themselves. Enter, stage left, Omer Stringer. Like Roy, Omer was from Ontario. Omer though was born in Algonquin Park and had been a fishing guide there. Roy used to talk appreciatively about the wonderfully simple but ingenious, solar-powered, reflector oven that Omer had built and regularly used in India. The RADAR technicians rallied around Omer's oven because he baked the tastiest, weeviless biscuits!

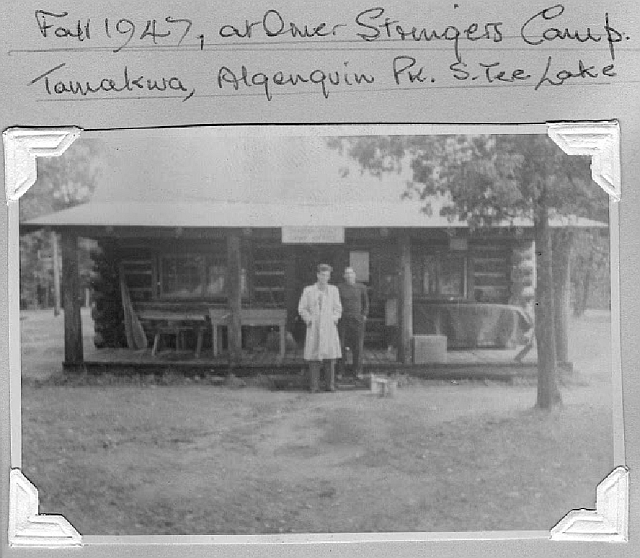

Omer later became something of a legendary canoeist and outdoorsman, Omer had co-founded Camp Tamakwa in Algonquin Park and constructed its first buildings on Tea Lake in 1936. Omer later attained considerable fame for founding the Roots Company which makes outdoorsy clothes and cedar-strip Beaver canoes. After the war, Roy and Sylvia re-connected with Omer, at least periodically. For instance, as a preteen in about 1970, when I was on a car-camping trip with my parents across northern Ontario, we dropped in for a visit at Omer's camp in Algonquin and he took me out for a paddle. My parents had filled me with such awe-filled stories about Omer's canoeing prowess that I felt awkward and shy.

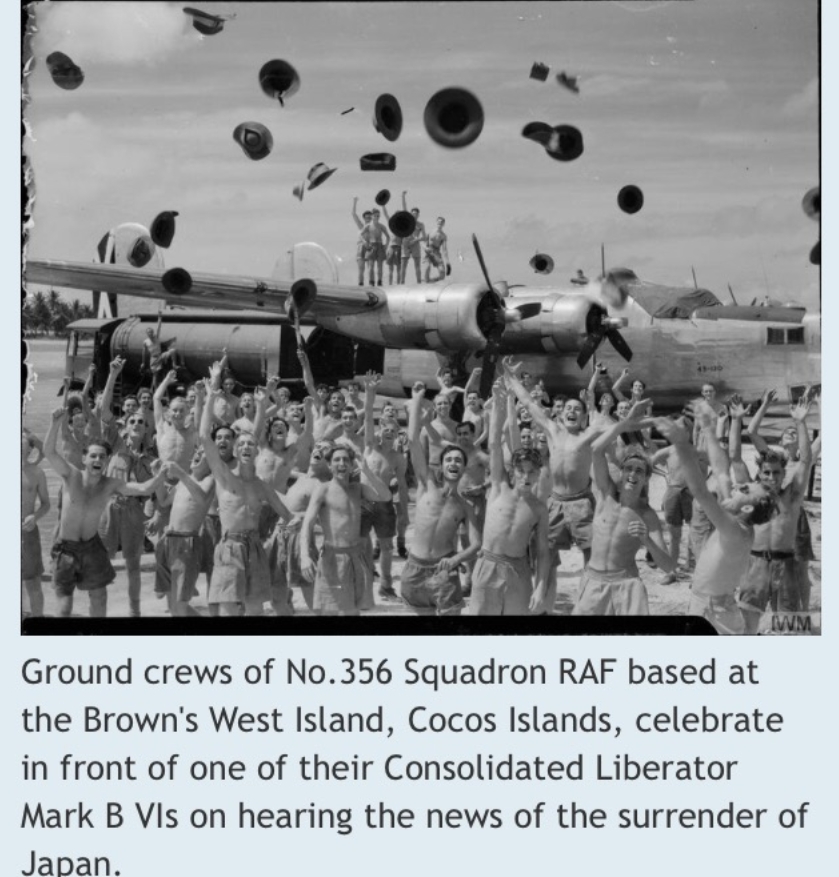

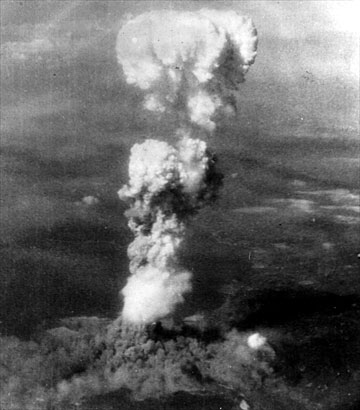

The final war story that I'll share here is about how my Dad built a radio during the war. As a child I recall being surprised that he could just build a radio. It still astounds me. But the more interesting thing about this story, to me at least, is that he described how, when he and fellow crew members gathered around the radio, they heard shocking news. The broadcast announced that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. This dates their radio experience to August 6, 1945.

Later in life, when Roy became deeply involved

in the peace movement, the primary issue which motivated his antiwar

activism was his fervent opposition to nuclear weapons. By the 1950s

he and Sylvia were already attending protests in Ottawa organised by the

Committee Against Radiation Hazards, which raised public awareness about

the hazards of nuclear fallout caused by atmospheric testing of atomic

bombs. In the early 1960s he and Sylvia were active with the Canadian

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament which opposed atmospheric testing of

nuclear weapons and protested when Prime Minister Pearson agreed to allow

US Bomarc nuclear missiles to be based in Canada. Many other peace

organisations with which he was involved in the 1970s, like Operation

Dismantle and the Gloucester Peace Group, were also focused on

nuclear-weapons issues. In the 1980s, Roy was active with Veterans Against

Nuclear Arms and the Alliance for Nonviolent Action, and was even

arrested, while wearing his wartime medals, at a civil disobedience action

timed to coincide with Remembrance Day.

Click here to learn more about

his peace movement activities.

This was classic Roy. He was sharp, quick witted, and could get straight to the point. Although extremely quiet, shy and averse to public speaking, he took his last public opportunity to promote peace. He did this by conjuring up the image of people marching blindly off to war behind this archetypal Canadian symbol. Roy did not want his work legacy to be remembered as in any way supporting or leading to war through militarism or nationalism. It is in this

context of my father's half-century of involvement in Canada's anti-war

movement, that I choose to remember his memories of World War II. Postscript: I was always intrigued by my Dad's memories of having lived in India. His time there was part of what inspired me to visit India for myself. It was in 1979-1980, between my BA and MA years in anthropology, that I traveled around India and three neighbouring countries for about eight months. That journey opened my eyes to a whole other world and changed my life for ever. I visited almost all of the places that my Mom had marked on a map of India which she sewed for my Dad soon after they met in 1945. Have something to add? Richard Sanders <overcoat@rogers.com> |

|

In 1942, at the tender age of 18,

my Dad (Roy) joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was selected for

training to become a RADAR technician and left the family's small farm

near Bloomfield. Leaving behind Prince Edward County, on the north

shore of Lake Ontario, he began a journey that would take him to the far

side of the earth. (

In 1942, at the tender age of 18,

my Dad (Roy) joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was selected for

training to become a RADAR technician and left the family's small farm

near Bloomfield. Leaving behind Prince Edward County, on the north

shore of Lake Ontario, he began a journey that would take him to the far

side of the earth. ( her

they would experience in India. It also gave Roy an opportunity to observe

the ill-treatment of blacks in Texas, which was still an apartheid

society. The whole experience was an eye opener for Roy who had

likely never been able to venture outside

of The County before.

her

they would experience in India. It also gave Roy an opportunity to observe

the ill-treatment of blacks in Texas, which was still an apartheid

society. The whole experience was an eye opener for Roy who had

likely never been able to venture outside

of The County before.

Roy and

other

technicians were not told -- for security

reasons -- which British base they were heading to in India. They were not even

told the name of the city where they should get off the plane. They were

supposed to be met in

India by military authorities who would identify themselves, and then

escort them to wherever they were supposed to be going. The first city where they

landed in India was Karachi, which is now in Pakistan. Once

there all the passengers, including the secret RADAR guys, were ordered off the plane.

But unfortunately, the British military in Karachi knew

nothing about who

these guys were, where they were supposed go, let alone why.

Roy and

other

technicians were not told -- for security

reasons -- which British base they were heading to in India. They were not even

told the name of the city where they should get off the plane. They were

supposed to be met in

India by military authorities who would identify themselves, and then

escort them to wherever they were supposed to be going. The first city where they

landed in India was Karachi, which is now in Pakistan. Once

there all the passengers, including the secret RADAR guys, were ordered off the plane.

But unfortunately, the British military in Karachi knew

nothing about who

these guys were, where they were supposed go, let alone why.

For

their part, the RADAR guys had been instructed not to tell anyone anything

about their mission! Eventually after two weeks or so, the RADAR crew

decided to get out of Karachi and

head for Britain's military HQ in the capital. After a 1000+ km

journey half way across the subcontinent, they reached the head office

in Delhi. There they finally found people who they could talk to

about their mission. These officers exclaimed "Where have you been! We've been waiting for you

for a month!" (They say military intelligence is a contradiction in

terms....)

For

their part, the RADAR guys had been instructed not to tell anyone anything

about their mission! Eventually after two weeks or so, the RADAR crew

decided to get out of Karachi and

head for Britain's military HQ in the capital. After a 1000+ km

journey half way across the subcontinent, they reached the head office

in Delhi. There they finally found people who they could talk to

about their mission. These officers exclaimed "Where have you been! We've been waiting for you

for a month!" (They say military intelligence is a contradiction in

terms....) Roy told another story about the brief time he had in Delhi before

being deployed to India's east coast. For some reason he had

occasion to be inside a building for "officers." This was perhaps the

military HQ where they went upon their arrival. Roy saw a sign there

instructing officers: "No shooting the natives from the balcony."

Was it acceptable to shoot Indians from other vantage points, besides

balconies? (Note: In Shimla, the cool, mountain city in Himachal

Pradesh that was the British Raj's Indian capital during summer months,

the main drag had signs saying: "No dogs or Indians allowed on the

street.")

Roy told another story about the brief time he had in Delhi before

being deployed to India's east coast. For some reason he had

occasion to be inside a building for "officers." This was perhaps the

military HQ where they went upon their arrival. Roy saw a sign there

instructing officers: "No shooting the natives from the balcony."

Was it acceptable to shoot Indians from other vantage points, besides

balconies? (Note: In Shimla, the cool, mountain city in Himachal

Pradesh that was the British Raj's Indian capital during summer months,

the main drag had signs saying: "No dogs or Indians allowed on the

street.")

In 1943, Roy was initially posted to

Squadron 354's air base at Cuttack, in India's Orissa state. The

Squad was initially posted there between August 1943 and October 1944.

The photo at left was taken within the Cuttack airbase. Roy's

writing on the back says: "At an old Indian Temple in Cuttack Camp."

He lists the men as Sandy, Priest, Jamie and Saul.

In 1943, Roy was initially posted to

Squadron 354's air base at Cuttack, in India's Orissa state. The

Squad was initially posted there between August 1943 and October 1944.

The photo at left was taken within the Cuttack airbase. Roy's

writing on the back says: "At an old Indian Temple in Cuttack Camp."

He lists the men as Sandy, Priest, Jamie and Saul.

In

October 1944, Squadron 354 was deployed to

Minneriya in Ceylon. Then still part of British India,

this is now the island country of Sri Lanka. A book called

In

October 1944, Squadron 354 was deployed to

Minneriya in Ceylon. Then still part of British India,

this is now the island country of Sri Lanka. A book called

This

threat came not from enemy warplanes but from another airborne menace,

namely mosquitoes laced with the

This

threat came not from enemy warplanes but from another airborne menace,

namely mosquitoes laced with the  There

were other forms of wildlife around the base trying to get into their

food. Roy remembered that they would sometimes see hyenas in or

around the Cuttack airfield. Wondering how common this might

have been, I searched online and found a book which remarks that "the

woods which skirt the western frontier of Cuttack...are filled with

wild animals, such as Tigers, Leopards, Panthers, Hyenas, Bears..."

Although this

There

were other forms of wildlife around the base trying to get into their

food. Roy remembered that they would sometimes see hyenas in or

around the Cuttack airfield. Wondering how common this might

have been, I searched online and found a book which remarks that "the

woods which skirt the western frontier of Cuttack...are filled with

wild animals, such as Tigers, Leopards, Panthers, Hyenas, Bears..."

Although this

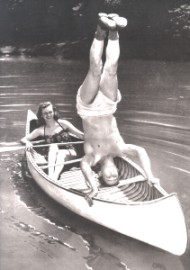

Roy

and Sylvia had described with glee a time when they'd seen him go out into the

whitecaps of a windblown lake where he stood on his head in the canoe.

This may have been about twenty years earlier, in 1947, when they had

their honeymoon at Omer's Camp in the Park. (The photo, above left,

showing Omer up to his usual tricks in Algonquin Park, was found

Roy

and Sylvia had described with glee a time when they'd seen him go out into the

whitecaps of a windblown lake where he stood on his head in the canoe.

This may have been about twenty years earlier, in 1947, when they had

their honeymoon at Omer's Camp in the Park. (The photo, above left,

showing Omer up to his usual tricks in Algonquin Park, was found

Having

researched my Dad's military experiences during the war, I've found that

towards the end of the war he was based on the Cocos Islands in the Indian

Ocean. The Cocos are off the coast of Java, half way between India

and Australia. Although Roy did mention having been briefly

stationed on these islands during the war, it was not clear to me when

that deployment had taken place. Recently I found some military

records reprinted in

Having

researched my Dad's military experiences during the war, I've found that

towards the end of the war he was based on the Cocos Islands in the Indian

Ocean. The Cocos are off the coast of Java, half way between India

and Australia. Although Roy did mention having been briefly

stationed on these islands during the war, it was not clear to me when

that deployment had taken place. Recently I found some military

records reprinted in

So

this it seems was where Roy and fellow RADAR aircrew tuned in to the news

that the US had dropped nuclear bombs on Japan. We now know that the

obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not needed to end the war.

American military forces knew full well that Japan was ready to surrender.

So

this it seems was where Roy and fellow RADAR aircrew tuned in to the news

that the US had dropped nuclear bombs on Japan. We now know that the

obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not needed to end the war.

American military forces knew full well that Japan was ready to surrender.